To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Click on images to enlarge.

Crop Conditions

The season is chugging along and we’ve made it to August without any major curveballs in MA—phew. We know that many farms in Vermont have not been as fortunate; the remnant storms from hurricane Beryl hit hard there and farms saw devastating floods, some for the second year in a row. The Vermont Agency of Ag has opened a flood loss survey to capture the extent of the damage. Heat and high humidity along with intermittent storms continue to push disease development, though, especially in cucurbits and tomatoes, and we had our first cases of downy mildew in basil and cucumber this week. We are in the peak of harvest season with all the usual suspects plus melon harvest continuing, onions and potatoes starting to come in, and the tomato crop is heavy!

The season is chugging along and we’ve made it to August without any major curveballs in MA—phew. We know that many farms in Vermont have not been as fortunate; the remnant storms from hurricane Beryl hit hard there and farms saw devastating floods, some for the second year in a row. The Vermont Agency of Ag has opened a flood loss survey to capture the extent of the damage. Heat and high humidity along with intermittent storms continue to push disease development, though, especially in cucurbits and tomatoes, and we had our first cases of downy mildew in basil and cucumber this week. We are in the peak of harvest season with all the usual suspects plus melon harvest continuing, onions and potatoes starting to come in, and the tomato crop is heavy!

We look forward to seeing some of you tomorrow at Bardwell Farm in Hatfield where we will hear about Harrison’s use of soil moisture sensors and automation to dial in irrigation in tunnel crops, irrigation water quality and testing, and pest management including how climate change is affecting vegetable pests with a focus on managing Phytophthora blight in peppers and squash. 5-6:30 with a pizza party to follow!

Basil

Basil downy mildew (BDM) continues to spread, and was observed on ‘Eleonora’ and ‘Keira’ basil in Franklin Co. this week. By this time every year, it’s fairly inevitable that BDM will be present in MA. Plan on growing BDM-resistant varieties starting in July to ensure clean harvests. Based on varietal responses in UMass trials, a recommended combination is to grow Prospera and Passion, and then introduce the new Prospera Active (which contains a 2nd BDM resistance gene in addition to the gene in the original Prospera) later in the season. Conventional growers can increase their protection with fungicides. Effective materials include Quadris, Reason, Revus, Orondis Gold, Orondis Opti, Ranman, and phosphorous acid fungicides. For more information on BDM-resistant basil varieties and labeled fungicides, see our article in the December 14, 2023 issue. Let us know (umassveg@umass.edu) if you see downy mildew on any of the resistant varieties this summer so that we can help track the evolution of this important pest.

Basil downy mildew (BDM) continues to spread, and was observed on ‘Eleonora’ and ‘Keira’ basil in Franklin Co. this week. By this time every year, it’s fairly inevitable that BDM will be present in MA. Plan on growing BDM-resistant varieties starting in July to ensure clean harvests. Based on varietal responses in UMass trials, a recommended combination is to grow Prospera and Passion, and then introduce the new Prospera Active (which contains a 2nd BDM resistance gene in addition to the gene in the original Prospera) later in the season. Conventional growers can increase their protection with fungicides. Effective materials include Quadris, Reason, Revus, Orondis Gold, Orondis Opti, Ranman, and phosphorous acid fungicides. For more information on BDM-resistant basil varieties and labeled fungicides, see our article in the December 14, 2023 issue. Let us know (umassveg@umass.edu) if you see downy mildew on any of the resistant varieties this summer so that we can help track the evolution of this important pest.

Celery

Celery anthracnose was confirmed this week at a farm in Hampshire Co. and is suspected at another farm in Franklin Co. This disease causes a range of symptoms – small, sunken, elliptical lesions or cracks on stalks, curling leaves and twisting petioles, pale green discoloration and stunting, ruptured lesions on outer stalks often with adventitious roots on the inside, and slimy dark rot of the heart tissue. For more information and management see the article in this issue.

Celery anthracnose was confirmed this week at a farm in Hampshire Co. and is suspected at another farm in Franklin Co. This disease causes a range of symptoms – small, sunken, elliptical lesions or cracks on stalks, curling leaves and twisting petioles, pale green discoloration and stunting, ruptured lesions on outer stalks often with adventitious roots on the inside, and slimy dark rot of the heart tissue. For more information and management see the article in this issue.

Cucurbits

C ucurbit downy mildew was confirmed on cucumbers in Franklin County on Wednesday. Growers should now be including targeted fungicides in their weekly cucurbit spray programs. Cucumbers and cantaloupes are most at-risk but it is reasonable to apply protectant and targeted sprays to all cucurbit crops. For the current cucurbit spray recommendations see this article from earlier this year.

ucurbit downy mildew was confirmed on cucumbers in Franklin County on Wednesday. Growers should now be including targeted fungicides in their weekly cucurbit spray programs. Cucumbers and cantaloupes are most at-risk but it is reasonable to apply protectant and targeted sprays to all cucurbit crops. For the current cucurbit spray recommendations see this article from earlier this year.

Squash vine borer damage is still being reported around MA. There are several diseases that can also cause plants to yellow and collapse (e.g. Phytophthora blight, bacterial wilt, plectosporium) but if you suspect vine borers, look near the base of the plant along the stem for a small hole and/or pile of sawdust-like frass and open up the stem to find white, grub-like caterpillars inside the stem. There is nothing to do about them now, but they will survive in the plant residue and become an increasing problem in future years if not controlled.

|

Trap location

|

SVB

|

|---|---|

|

Whately

|

1 |

|

North Easton

|

2 |

|

Sharon

|

4 |

|

Westhampton

|

2 |

|

Spray thresholds: Thick-stemmed cucurbits only. 5 moths/week for bush-type cucurbits. 12 moths/week for vining cucurbits.

|

|

Nightshades

Verticillium wilt is suspected from an eggplant sample from Hampshire Co. this week. This disease is caused by a soil-borne fungus that infects and clogs the water-conducting tissue of the plant. Leaves of infected plants wilt and become dull and pale green. Plants’ vascular tissue is organized like a bundle of tubes, and Verticillium often initially infects only some of the tubes, causing leaves to wilt on only one side of the midrib. Infected leaves also frequently develop an angular, mottled look. Verticillium has a wide host range and is difficult to manage using crop rotations. There are also no effective chemical controls (there are many biopesticides labeled for this disease but insufficient data supporting their efficacy in the field). There are no truly resistant varieties but some varieties, including Epic, Long Purple, Rosa Bianca, Casper, and Classic, may maintain high yields despite infection. Maintaining adequate soil moisture and fertility will also help to maximize plant health and yields in affected plants.

Verticillium wilt is suspected from an eggplant sample from Hampshire Co. this week. This disease is caused by a soil-borne fungus that infects and clogs the water-conducting tissue of the plant. Leaves of infected plants wilt and become dull and pale green. Plants’ vascular tissue is organized like a bundle of tubes, and Verticillium often initially infects only some of the tubes, causing leaves to wilt on only one side of the midrib. Infected leaves also frequently develop an angular, mottled look. Verticillium has a wide host range and is difficult to manage using crop rotations. There are also no effective chemical controls (there are many biopesticides labeled for this disease but insufficient data supporting their efficacy in the field). There are no truly resistant varieties but some varieties, including Epic, Long Purple, Rosa Bianca, Casper, and Classic, may maintain high yields despite infection. Maintaining adequate soil moisture and fertility will also help to maximize plant health and yields in affected plants.

Sweet corn

European corn borer pressure is variable this week, with trap captures of the predominant NY strain ranging from 0-10, similar to last week. Historically, this is when we start to see numbers increase as the second generation of ECB starts emerging in earnest.

Corn earworm numbers are highly variable across trapping locations in MA, but most traps indicate a 4-day spray interval is warranted at this time.

Fall armyworm numbers caught in pheromone traps are low, but folks are seeing lots of damage nonetheless, indicating the pheromone traps are not working very well. This means farmers should be scouting their fields for fall armyworm damage—large raggedy holes in pre-tassel and whorl stage corn—and spray if the threshold is reached; 15% infested for pre-tassel and 30% infested for whorl stage.

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | FAW | CEW | CEW SPRay interval* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western MA | |||||||

| North Adams | 1714 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Richmond | 1539 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| South Deerfield | 1844 | Whately | - | - | - | - | - |

| Easthampton | 1773 | Northampton | n/a | n/a | n/a | 19.5 | 4 days |

| Chicopee Falls | 1888 | Granby | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 days |

| Granville | 1615 | Southwick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 4 days |

| Central MA | |||||||

| Leominster | 1705 | Leominster | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lancaster | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 days | ||

| Northbridge | 1722 | Grafton | 2 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 days |

| Worcester | 1721 | Spencer | 2 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 4 days |

| Eastern MA | |||||||

| Bolton | 1731 | Bolton | 2 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 4 days |

| Stow | 1746 | Concord | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 days |

| Lawrence | 1769 | Haverhill | 10 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 4 days |

| Ipswich | 1729 | Ipswich | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 4 days |

| Harvard | 1726 | Littleton | 2 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 4 days |

| - | - | Millis | 0 | 0 | n/a | 60 | 4 days |

| Sharon | 1690 | North Easton | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sharon | 0 | 0 | n/a | 150 | 3 days | ||

| - | - | Sherborn | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 days |

| Providence, RI | 1749 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | 13 | 49 | 4 days |

| Swansea | 10 | 0 | - | 14 | 4 days | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest * If 2+ days above 80°F occur, shorten spray interval by 1 day. ** If CEW trap captures are below 1.4 moths/week, scout block for ECB and FAW caterpillars and make a pesticide application if 12% of plants in a 50-plant sample are infested. *** Count is for four days only |

|||||||

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Multiple/Miscellaneous Crops

Two-spotted spider mite (TSSM) populations are increasing on solanaceous crops, especially in high tunnels, but we also confirmed them on celery this week. The celery was being grown in a high tunnel that housed TSSM-infested tomatoes last year. TSSM favor hot and dry conditions, so they are common in high tunnel crops. Large populations will produce visible webbing that can completely cover leaves, and mites will hide under the webbing, making them difficult to reach with pesticide sprays. Adults and nymphs feed on crop tissue with piercing-sucking mouthparts, causing a speckled appearance and eventually leading to leaf and fruit deformities and loss of plant vigor. The predatory mite Amblyseius fallacis can be released in high tunnels to control TSSM. To successfully control TSSM with pesticides, they must be applied early on, before populations explode. Use selective materials that won’t kill beneficials to help keep mite populations in check. Effective selective materials include Agri-Mek, Acramite, Movento, Oberon, Kanemite, and Portal XLO. Check labels for labeled crops and restrictions on use in greenhouses or high tunnels. Organic growers can use insecticidal soap (M-Pede) and horticultural oils (e.g. Trilogy, Suffoil X, and Golden Pest Spray Oil). These can be effective, especially if utilized early and regularly with good leaf coverage.

Two-spotted spider mite (TSSM) populations are increasing on solanaceous crops, especially in high tunnels, but we also confirmed them on celery this week. The celery was being grown in a high tunnel that housed TSSM-infested tomatoes last year. TSSM favor hot and dry conditions, so they are common in high tunnel crops. Large populations will produce visible webbing that can completely cover leaves, and mites will hide under the webbing, making them difficult to reach with pesticide sprays. Adults and nymphs feed on crop tissue with piercing-sucking mouthparts, causing a speckled appearance and eventually leading to leaf and fruit deformities and loss of plant vigor. The predatory mite Amblyseius fallacis can be released in high tunnels to control TSSM. To successfully control TSSM with pesticides, they must be applied early on, before populations explode. Use selective materials that won’t kill beneficials to help keep mite populations in check. Effective selective materials include Agri-Mek, Acramite, Movento, Oberon, Kanemite, and Portal XLO. Check labels for labeled crops and restrictions on use in greenhouses or high tunnels. Organic growers can use insecticidal soap (M-Pede) and horticultural oils (e.g. Trilogy, Suffoil X, and Golden Pest Spray Oil). These can be effective, especially if utilized early and regularly with good leaf coverage.

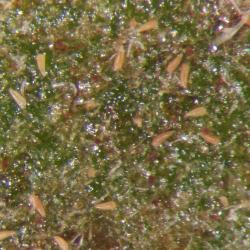

Tomato russet mites (Aculops lycopersici) were spotted on tomatoes in a high tunnel in Worcester Co. this week. Like TSSM, these mites are generally a pest of solanaceous crops and are more common when conditions are hot and dry, such as in greenhouses and high tunnels. However, russet mites are much smaller than TSSM and cannot be seen without a powerful hand lens or microscope. They have only two pairs of legs which are located at the front of their body, and they are slender, cone-shaped, and cream, tan, or yellow in color. Due to their size, this pest is often only detected after substantial crop damage has occurred. Symptoms typically begin on the lowest parts of plants and move upwards. Feeding by russet mites causes leaves to curl and turn yellow or bronze, sometimes with a glossy appearance on the undersides of leaves. Leaves and petioles may wither and die while the stem remains intact but with a similar bronze or brown discoloration. Symptoms are often mistaken for those of disease or nutrient deficiency. Russet mites do not produce webbing as spider mites do.

Tomato russet mites (Aculops lycopersici) were spotted on tomatoes in a high tunnel in Worcester Co. this week. Like TSSM, these mites are generally a pest of solanaceous crops and are more common when conditions are hot and dry, such as in greenhouses and high tunnels. However, russet mites are much smaller than TSSM and cannot be seen without a powerful hand lens or microscope. They have only two pairs of legs which are located at the front of their body, and they are slender, cone-shaped, and cream, tan, or yellow in color. Due to their size, this pest is often only detected after substantial crop damage has occurred. Symptoms typically begin on the lowest parts of plants and move upwards. Feeding by russet mites causes leaves to curl and turn yellow or bronze, sometimes with a glossy appearance on the undersides of leaves. Leaves and petioles may wither and die while the stem remains intact but with a similar bronze or brown discoloration. Symptoms are often mistaken for those of disease or nutrient deficiency. Russet mites do not produce webbing as spider mites do.

Sulfur sprays such as Microthiol Disperss are effective and OMRI-certified but should not be used when plants are flowering or when temperatures will exceed 90° F. Neem oil or azadirachtin may also be effective. Other miticides may also be labeled for use on indoor and/or outdoor tomatoes: always check the label and follow label instructions. The predatory mite Amblyseius andersoni can be effective in greenhouses and tunnels for preventing infestation or controlling low pest numbers, and additionally controls broad mites and TSSM. Wait 48 hours after chemical application before releasing predatory mites. Solanaceous plants (nightshade, pepper, petunia, etc.) and bindweed can also serve as hosts for tomato russet mite and should be controlled in and around greenhouses, high tunnels, and field crops.

Stink bugs have been causing damage on crops including corn and peppers. Besides the invasive brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) which is a common pest on a variety of fruit and vegetable crops, there are a number of other stink bug species, such as the native brown stink bug, which are minor or infrequent pests of a broad range of crops. BMSB can be distinguished by the presence of alternating dark and light segments on the edges of the abdomen and white stripes on the legs and antennae, which brown stink bugs lack. Nymphs and adults use their straw-like mouthparts to inject enzymes into plant tissue and suck out the resulting juices. They feed on the stalk and leaves of corn, causing yellowing, with heavy feeding causing twisted or deformed stalks. Seedlings are at the highest risk, with moderate feeding unlikely to significantly affect yield in larger plants. They will also feed on the fruits of peppers and tomatoes, causing shallow injury to the flesh and cloudy spots of discoloration visible on the skin. More severe damage can cause scarring, cat-facing, and internal damage. Stink bugs are highly mobile and have thick exoskeletons, making them somewhat resistant to most insecticide treatments. See the tomato insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for more information on chemical control. An abundance of natural enemies on farms can also help keep stink bug pressure low if they are not disrupted by broad-spectrum insecticides. Some stink bug species, including the spined soldier bug, are themselves predators and can help control other pests. These can often be distinguished by the presence of prominent spines on their shoulders.

Stink bugs have been causing damage on crops including corn and peppers. Besides the invasive brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) which is a common pest on a variety of fruit and vegetable crops, there are a number of other stink bug species, such as the native brown stink bug, which are minor or infrequent pests of a broad range of crops. BMSB can be distinguished by the presence of alternating dark and light segments on the edges of the abdomen and white stripes on the legs and antennae, which brown stink bugs lack. Nymphs and adults use their straw-like mouthparts to inject enzymes into plant tissue and suck out the resulting juices. They feed on the stalk and leaves of corn, causing yellowing, with heavy feeding causing twisted or deformed stalks. Seedlings are at the highest risk, with moderate feeding unlikely to significantly affect yield in larger plants. They will also feed on the fruits of peppers and tomatoes, causing shallow injury to the flesh and cloudy spots of discoloration visible on the skin. More severe damage can cause scarring, cat-facing, and internal damage. Stink bugs are highly mobile and have thick exoskeletons, making them somewhat resistant to most insecticide treatments. See the tomato insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for more information on chemical control. An abundance of natural enemies on farms can also help keep stink bug pressure low if they are not disrupted by broad-spectrum insecticides. Some stink bug species, including the spined soldier bug, are themselves predators and can help control other pests. These can often be distinguished by the presence of prominent spines on their shoulders.

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Celery Anthracnose: The Leaf Curl Disease

Since 2010, celery anthracnose (aka leaf curl) has become a major challenge in large celery production regions in Michigan and Ontario and sporadically occurs in the Northeast. It does not appear to affect celeriac or other closely related crops. Symptoms, listed from the first noticeable to the most severe, include:

Since 2010, celery anthracnose (aka leaf curl) has become a major challenge in large celery production regions in Michigan and Ontario and sporadically occurs in the Northeast. It does not appear to affect celeriac or other closely related crops. Symptoms, listed from the first noticeable to the most severe, include:

- Small, slightly sunken, light brown elliptical lesions or cracks on the stalks

- Curling leaves (usually downward cupping) and twisting petioles

- Pale green (not yellowed) color +/- stunting

- Sunken dark brown or black lesions along stalk edges, particularly on young heart tissue

- Ruptured, greenish to light brown outer stalk lesions, frequently with gall tissue or adventitious roots on the inside

- Slimy, brown to black rot of the heart tissue that leaves intact outer leaves standing

Celery leaf curl, which describes the most recognizable early symptom, is the descriptive name used when this disease first showed up—before the causal pathogen was identified. We also call it celery anthracnose because we now know that an anthracnose fungus causes the issue.

Disease biology

Celery anthracnose is caused by a tightly related cluster of Colletotrichum (pronounced cauli-TOT-rick-um) species, formerly referred to as Colletotrichum acutatum. Researchers have genetically determined that at least two species cause celery leaf curl. C. fioriniae and C. nymphaeae are the major species causing celery crop losses in Ontario, Canada. C. nymphaeae has also been implicated in Japanese outbreaks of celery anthracnose. These are different from the main anthracnose species that attack tomato, pepper, and vine crops. C. fioriniae is also responsible for garlic anthracnose (aka orange fuzzy scape disease), bitter rot of apples and bitter rot of pears while C. nymphaeae causes strawberry anthracnose.

How celery anthracnose arrives on farms is unclear. Some work suggests that seeds may carry the disease, which helps explain why symptoms often start in greenhouse transplant production. The pathogen is easily spread in the field by water and splashing soil. The life span of the pathogen in the soil isn’t well understood at this point. Once on the farm, celery anthracnose fungi can infect several weeds. Common lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, yellow nutsedge, oakleaf goosefoot, and common groundsel can all harbor celery anthracnose without clearly expressing symptoms. An important feature of celery anthracnose is its ability to infect a plant then lay quietly in an undetectable, asymptomatic state (a latent or quiescent infection) until environmental conditions become favorable.

Celery anthracnose thrives under warm, wet conditions. Rapid growth occurs when temperatures are 77 to 86°F, with substantially more disease development at 86°F than 77°F. Temperatures as cool as 60°F will support fungal growth and spread, but field progression will be slow. Wet leaves also facilitate leaf curl development. Long wetting periods of 48 to 96 hours best promote outbreaks, though as little as 12 hours is sufficient to cause disease. It takes 3-5 days after infection for the small, sunken stalk lesions to appear. The curling starts just days after the initial lesions. Celery leaf curl frequently develops when it has been very hot with heavy thunderstorms followed by high humidity. Overhead irrigation and poor airflow due to weedy fields also increase leaf wetness periods and exacerbate disease.

Full disease outbreaks in celery can cause heavy losses. When environmental conditions favor disease, infection can range from 17 to 100% and cause marketable yield loss of up to 80%. In cooler, drier weather, infections can be as low as 1 to 10% with very little to no loss in marketability. If an infection is mild and the heart tissue is unaffected, some plants with celery leaf curl can be marketed after an aggressive trimming.

Cultural Management

Preplant

- Become familiar with the symptoms.

- Keep the greenhouse free of weeds.

- Scout your plug trays before transplanting into the field.

- Remove suspicious seedlings and treat the remaining ones, or consider starting over using new plug trays.

- Consider your rotations and don’t plant into fields with a recent history of celery or garlic anthracnose.

Rotational considerations are under-studied at the moment and are currently based on general precaution and common sense. For each of the following scenarios, assess your farm’s risk profile (history, severity of disease) and your comfort level for rotating between or planting near other susceptible crop hosts. Currently, there isn’t a clear understanding of whether C. nymphaeae will move from strawberries to celery and vice versa. To be cautious, don’t move from an infected celery or strawberry planting into the other crop when doing field work. Avoid rotating with garlic following an outbreak of orange fuzzy scape or celery anthracnose. Avoid planting near apple and pear trees that have a recent history of bitter rot.

In Season

- Use drip irrigation if there is celery leaf curl in the transplants.

- Minimize overhead irrigation and splashing. Mulch can also reduce weed pressure.

- Remove infected plants to minimize field spread of celery anthracnose.

- Control weeds in infected fields to improve airflow and reduce the risk of carryover on weedy hosts.

- Harvest fields with infections as soon as the plants are of marketable size to reduce the chances of developing heart lesions.

- Disc infected crop residue as soon as possible to promote break-down and reduce inoculum.

- Rotate away from celery for 3 to 4 years.

- Scout fields and treat at first symptoms using effective materials or preventatively during periods of highly favorable (hot, wet) weather.

Scouting

Scout your celery planting during a long hot period or a few days after a short one. Hold off on scouting until the foliage dries. Pay particular attention if you’ve had heavy rain, high humidity, or overhead irrigation. Look for curling leaves and then examine the stalks and hearts of plants more closely. Foliar symptoms are usually absent. Remember that aster yellows requires the presence of leaf hoppers for transmission, produces pronounced yellowing, and does not cause dark stem lesions.

Resistant varieties

Some varieties show some tolerance to celery anthracnose, though no variety is resistant and all varieties screened to date will show some disease. Variety screenings were undertaken by the University of Guelph so cultivars identified as somewhat tolerant should be well adapted locally. Susceptible varieties used by Michigan State for leaf curl experiments are also included (Table 1).

| tolerance to celery anthracnose | Variety |

|---|---|

| Least susceptible | Merengo Hadrian Geronimo Balada |

| Moderately susceptible | Sabroso TZ 6010 |

| Highly susceptible | Plato TZ 9779 Stetham Kelvin Nero Green Bay Dutchess Tango |

Chemical control

Fungicides can help slow celery anthracnose progression and retain marketable yield. Applications should be directed at the most susceptible young tissue in the heart of the plant. Trials examining fungicide efficacy most often make 1 application before the disease starts, so keep in mind that field results may not be as good if sprays begin after disease is found. Stobilurin fungicides (Group 11) best reduce celery leaf curl progression in the field and best help maintain yield. Cabrio consistently performs well. Stobilurin fungicides really should be applied with a protectant and be rotated with non-group 11 fungicides because of resistance concerns. Treat any infected seedlings with a group 11 when they are set in the field. Cuprous oxide forms of copper can help in low pressure weather conditions, but do little when environmental conditions are highly favorable. See Table 2 for which fungicides are available to treat celery anthracnose, and early and late blights of celery.

| Fungicide | Active Ingredient | FRAC Group | Diseases Listed | Rate & Notes | PHI (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bravo WeatherStik | Chlorothalonil | M5 | Early & Late Blight | 2-3 pt/A, protectant | 7 |

| Cabrio | Pyraclostrobin | 11 | Anthracnose, Early & Late Blight | 12-16 oz /A, 64 oz/yr max ≤ 2 sequential apps |

0 |

| Flint | Trifloxystrobin | 11 | Early & Late Blight | 2-3 oz/A | 7 |

| Fontelis | Penthiopyrad | 7 | Early & Late Blight | 14-24 fl oz/A | 3 |

| Howler EVOOG | Pseudomonas chlororaphis strain AFS009OG | BM02 | Anthracnose, Alternaria, Late Blight |

Field Applications 40-120 oz. wt./A Greenhouse Applications 2.5-7.5 lbs./100 gallons |

0 |

| Luna Sensation | Fluopyram + Trifloxystrobin | 7+11 | Early & Late Blight; Rhizoctonia suppression | 5.8 fl oz/A | 7 |

| Merivon Xemium | Pyraclostrobin/fluxapyroxad | 11+7 | Anthracnose, Early & Late Blight | 4-11 fl oz, 3 apps/yr | 1 |

| Miravis Prime | Pydiflumetofen + Fludioxonil | 7 + 12 | Alternaria, Early & Late Blight | 9.2-13.4 fl oz/A | 0 |

| OSO 5%OG | Polyoxin D zinc salts | 19 | Alternaria | 6.5-13.0 fl oz/A | 0 |

| Pristine | Pyraclostrobin/boscalid | 11 + 7 | Anthracnose, Early & Late Blight | 10-15 oz/A, 2 apps/yr | 0 |

| Quadris | Azoxystrobin | 11 | Early & Late Blight | 9.0-15.5 fl oz/A, 1 spray then rotate groups | 0 |

| Quilt | Azoxystrobin/propiconazole | 11 + 3 | Early & Late Blight | 14 fl oz/A, max of 1.5 lb azoxystrobin products/yr | 14 |

| RegaliaOG | Extract of Reynoutria sachalinensis | P5 | Early blight | 0.5-1.5 quarts/A | 0 |

| Rhyme | Flutriafol | 3 | Anthracnose, Early & Late Blight | 5-7 fl oz/A | 7 |

| StargusOG | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain F727* | BM02 | Anthracnose, Early blight | 1-4 quarts/100 gallons | 0 |

| Switch | Cyprodinil/fludioxonil | 9 + 12 | Late Blight | 11-14 oz/A | 0 |

| Tilt | Propiconazole | 3 | Early & Late Blight | 4 fl oz/A | 14 |

| Various | Coppers | M1 | Check the label of your prefered formulation | ||

Forecasting models

Work at the University of Guelph has shown good disease control success by using the TOMCAST forecasting model with a threshold of 15 disease severity units to help time fungicide applications. Using TOMCAST instead of calendar schedule spraying will reduce the number of applications and make rotating fungicide groups much more achievable. Remember that protectant fungicides applied for celery early and late blight are generally effective against a broad range of diseases and may have a secondary benefit of allowing you to postpone treatment for anthracnose.

With good cultural practices and fungicide use, sporadic outbreaks can often be controlled enough to harvest a portion of an infected planting. While celery may not be a major crop in the Northeast, celery anthracnose tends to cause major losses when it shows up. There is ongoing research into celery leaf curl in Ontario and Pennsylvania which will hopefully lead to improved future control.

--Adapted from article by Elizabeth Buck, Cornell Vegetable Program

Summer Annual Grasses

I have heard from several people this season that it’s a “good year for grasses”. I cannot think of a specific reason why grasses as a whole group would be favored over other weeds this year, but that does not mean there is no reason, I just have not thought of one yet. Regardless of whether all grasses are growing better this year, or just some species, I thought it would be a good time to delve into grass ID 101, focusing on some intimidating-looking species I have seen recently.

Grass ID Basics

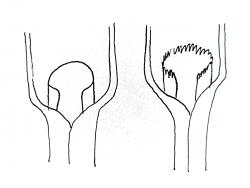

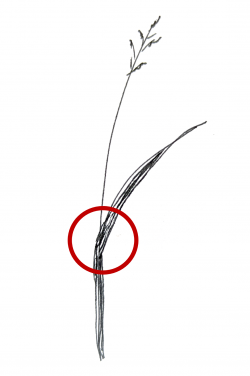

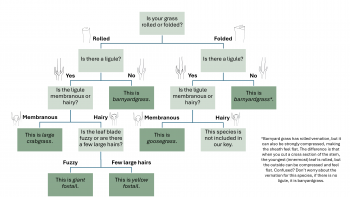

Grass identification is hard! Leaf shape tells you very little, and you do not want to wait until your grasses are setting seed to get a positive identification. What most grass identification keys focus on is an area known as the collar region – where the leaf blade meets the leaf stem (Fig. 1). You want to look for several different structures at this region—let’s walk through them:

Grass identification is hard! Leaf shape tells you very little, and you do not want to wait until your grasses are setting seed to get a positive identification. What most grass identification keys focus on is an area known as the collar region – where the leaf blade meets the leaf stem (Fig. 1). You want to look for several different structures at this region—let’s walk through them:

- The ligule is a papery sheath that wraps from the blade around the grass stem. It can be tall, short, membranous, hairy, or absent (Fig. 2).

- The auricles are finger-like protrusions that come out from the sides of the leaf blade at the collar region and wrap around the stem (Fig. 3).

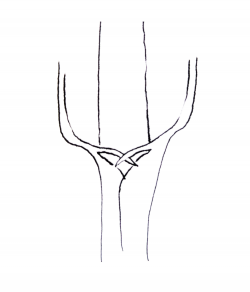

- Leaves can either be rolled or folded in the bud, called leaf vernation. This refers to how the newest blade is packed into the bud. You can usually tell whether a grass is rolled or folded by rolling it between your fingers. A smooth roll means rolled, a flip means folded, but sometimes it is more accurate to cut the stem crosswise and look at how the unfurled leaf is oriented (Fig. 4).

There are also characteristics of the leaf blade itself that can help you identify a grass. Whether the blade is smooth, hairy, rough, has a few long sparse hairs, or has prominent parallel- or mid-veins. If you use the key in the back of the Weeds of the Northeast book, figuring out these characteristics for your grass weed should at least get you close to the correct identification.

Why Identify Grass Species?

Identifying grass species may help you understand why you are seeing that grass in the first place and how to manage it moving forward. Grasses, like all weeds, can be classified by their lifecycle. Please check out the UMass fact sheet on weed life cycles if you do not know what that means. A few months ago, I wrote an article on winter annual weeds, because they were what we were seeing in the fields at the time. Now, for the most part, the lifecycle of winter annual plants is complete, and we do not see those species in the field anymore. Instead, we are seeing perennial and summer annual weed species.

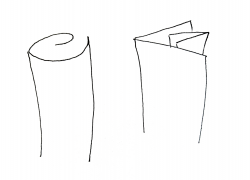

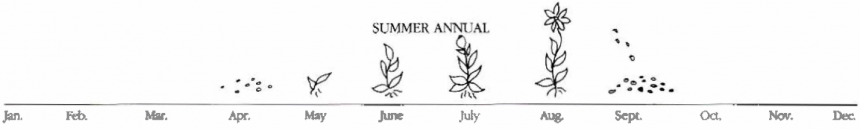

Summer annuals are plants that germinate in the spring, grow throughout the summer, and then set seed and die before winter (Fig. 5). Many of our crops are summer annuals – corn would be a prominent example – so there are a lot of summer annuals weeds that are difficult to control.

Figure 5. Lifecycle of a summer annual weed. Image: Bellinder et al. 1963

If you know your grass species you can figure out whether you are dealing with a summer annual, winter annual, or perennial grass and whether your perennial grass might be spreading though underground roots or whether you should be more concerned about seed set to reduce spread.

Summer Annual Grass Identification

There are many summer annual grass species, but this article is just going to focus on a few of the most common species I am currently seeing:

- yellow and giant foxtail (Setaria pumila and Setaria faberi)

- large crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis)

- goosegrass (Eleusine indica)

- barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli)

Try using the dichotomous key by answering the questions about each of the grasses pictured below to match the picture with the species. Click on images to enlarge them. If you successfully complete the dichotomous key with these species, try with one on your farm. Remember, this key only includes a few species, so you might pick one not listed here. Scroll to the bottom of the issue past the events section or click here to see the answers!

Try using the dichotomous key by answering the questions about each of the grasses pictured below to match the picture with the species. Click on images to enlarge them. If you successfully complete the dichotomous key with these species, try with one on your farm. Remember, this key only includes a few species, so you might pick one not listed here. Scroll to the bottom of the issue past the events section or click here to see the answers!

Notice I never asked a question about auricles. If you see auricles, you probably have a perennial grass, hence why it is not included in this particular key. Just learning how to identify grasses can be a lot, so I am going to save summer annual grass management for another article. Check back shortly for what to do once you know you have a summer annual grass where you do not want it.

--Written by Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist

Events

Water & Climate Change Twilight Meeting at Bardwell Farm – Hatfield, MA

When: Tomorrow! Friday, August 2, 2024, 5-7pm, with dinner and discussion to follow

Where: Bardwell Farm, 49 Main St., Hatfield, MA 01038

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension and CISA for a climate-themed twilight meeting at Bardwell Farm in Hatfield, MA!

- Lisa McKeag will share findings from her recent water quality survey of farms around MA and discuss potential risks and impacts of weather and climate change and rising year-round temperatures on agricultural water quality.

- Harrison Bardwell will show off his new automated irrigation system, and discuss irrigation practices and funded projects around the farm.

- Sue Scheufele will discuss increasing pest risks caused by a hotter climate on vegetable pests including an on-farm trial for managing Phytophthora blight in peppers hosted by Bardwell Farm.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

2024 UMass Crop & Animal Research Farm Tour - South Deerfield, MA

When: August 13, 2024, 3:30pm to 5:30pm

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA

Registration: Free. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension and the UMass College of Natural Sciences and Stockbridge School of Agriculture for the 2024 Crop & Animal Research Farm Tour! We will take a tour of the research farm and hear about ongoing research, then have pizza and plenty of time for discussion afterwards.

Research and projects presented will include:

- Student Farm Enterprise

- How native plant species used in pollinator habitats affect disease transmission in pollinators

- Exploring the benefits of living mulch for corn silage systems

- Vegetable variety trials for disease resistance and heat tolerance, including cucumbers, basil, and lettuce

- Corn earworm genetics

- Potato leafhopper control in potatoes

- Corn and sorghum intercropping reduces nitrogen loss and greenhouse gas emissions

- Genes and genetics in agriculture

Bees and Beyond: Pollinators at the Arboretum

When: Saturday, August 18, 2:00-3:30pm

Where: Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130

Registration: Free. Registration is required. Click here to register.

Join pollinator expert and UMass Extension educator Nicole Bell for a walk through the Arboretum’s meadows to find bees and other pollinators in their natural habitat. Nicole will use a sweep net to find and catch bees in the landscape so participants can see them up close, while we talk about the most common bees found in Massachusetts, where they live and what they eat, and the importance of places like the Arboretum for pollinator conservation.

Field Walk at Siena Farms - CANCELED ❌

We have unfortunately had to cancel this twilight meeting. Keep an eye out for another cut flower meeting coming up this fall!

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health - South Deerfield, MA

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Save the Date! Gaining Ground Farm Tour

When: Thursday, October 17, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Gaining Ground, 341 Virginia Rd., Concord, MA 01742

Join New Entry and UMass Extension for a farm tour of Gaining Ground Farm in Concord, MA!

Registration and event details coming soon.

Grass ID Activity Answers

A. Goosegrass

B. Barnyardgrass

C. Yellow foxtail

D. Giant foxtail

E. Large crabgrass

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.