To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Click on images to enlarge.

Crop Conditions

The cooler weather this week and in the forecast is much more pleasant for these long harvest days. Loads of beautiful peppers, tomatoes, and eggplants, bunches of greens and herbs, beans, summer squash, and cucumbers continue to come in. Cooler weather also leads to dew, and plants are wet, wet, wet, meaning more time for fungal diseases to infect foliage and spread more quickly—see Pest Alerts for details.

The cooler weather this week and in the forecast is much more pleasant for these long harvest days. Loads of beautiful peppers, tomatoes, and eggplants, bunches of greens and herbs, beans, summer squash, and cucumbers continue to come in. Cooler weather also leads to dew, and plants are wet, wet, wet, meaning more time for fungal diseases to infect foliage and spread more quickly—see Pest Alerts for details.

The Atlantic hurricane season lasts from June 1 to November 30 so we’re right in the middle of it, and NOAA forecasts that 2024 will be particularly active. We’ve had 4 named storms to date and according to NOAA, we can expect several more. The USDA issued a press release reminding growers of the ways they can prepare their farms for hurricane season, including:

- Having an emergency plan in place

- Securing important records and documents

- Knowing your insurance options (find your local FSA office here)

The full press release also includes links to USDA resources, including their Disaster Assistance Discovery Tool. The UVM Ag Engineering Team released a timely blog post this week—a Guide to Preparing High Tunnels for Extreme Weather, which not only covers high wind and heavy rain, but also heat and snow management.

Brassicas

Alternaria leaf spot and crown rot is spreading in brassica crops. Alternaria causes round leaf spots that coalesce into large blighted areas over time, and often develop concentric rings and fuzzy black sporulation. Symptoms often begin on lower leaves and move upwards. In broccoli and cauliflower, Alternaria will infect the head and cause beads or curds to turn brown. See the article in this issue for more information.

Black rot is also present in brassica crops. This is a bacterial disease that infects plants via wounds or hydathodes (tiny pores at the margins of leaves). When the bacteria enter through the hydathodes, it forms characteristic V-shaped lesions. The veins in affected leaf tissue often turn black, giving the disease its name. The pathogen clogs the plant’s vascular tissue. Bacterial diseases are notoriously hard to control once they begin. Copper can provide some control if applied early and regularly. Adding or alternating with Actigard has been shown to improve bacterial disease control. Disease spread can be minimized by avoiding working in fields when foliage is wet.

Black rot is also present in brassica crops. This is a bacterial disease that infects plants via wounds or hydathodes (tiny pores at the margins of leaves). When the bacteria enter through the hydathodes, it forms characteristic V-shaped lesions. The veins in affected leaf tissue often turn black, giving the disease its name. The pathogen clogs the plant’s vascular tissue. Bacterial diseases are notoriously hard to control once they begin. Copper can provide some control if applied early and regularly. Adding or alternating with Actigard has been shown to improve bacterial disease control. Disease spread can be minimized by avoiding working in fields when foliage is wet.

Chenopods

Cercospora leaf spot is showing up in beets and Swiss chard now. This fungal disease causes round leaf spots, surrounded by a red halo on red varieties of beets and Swiss chard. Leaf spots coalesce to form large blighted areas and can defoliate crops. The disease is favored by warm temperatures and humid conditions or long periods of leaf wetness. Incorporate diseased crop residue promptly after harvest to reduce overwintering inoculum. Fungicides can effectively control Cercospora if applied early and regularly. The most effective materials include Tilt and Miravis Prime; use the highest labeled rate of both. The most effective OMRI-listed materials are a tank mix of Double Nickel and a copper product.

Cercospora leaf spot is showing up in beets and Swiss chard now. This fungal disease causes round leaf spots, surrounded by a red halo on red varieties of beets and Swiss chard. Leaf spots coalesce to form large blighted areas and can defoliate crops. The disease is favored by warm temperatures and humid conditions or long periods of leaf wetness. Incorporate diseased crop residue promptly after harvest to reduce overwintering inoculum. Fungicides can effectively control Cercospora if applied early and regularly. The most effective materials include Tilt and Miravis Prime; use the highest labeled rate of both. The most effective OMRI-listed materials are a tank mix of Double Nickel and a copper product.

Cucurbits

Squash vine borer pheromone trap captures are rising again at some locations (Table 1), indicating the emergence of the next generation of adults. The larvae that result from this generation often bore into winter squash fruit, rendering them unmarketable and causing secondary rots. Pheromone traps should be moved to winter squash plantings at this time. Treatment with insecticides is warranted if trap counts rise above 5 moths/week.

Squash vine borer pheromone trap captures are rising again at some locations (Table 1), indicating the emergence of the next generation of adults. The larvae that result from this generation often bore into winter squash fruit, rendering them unmarketable and causing secondary rots. Pheromone traps should be moved to winter squash plantings at this time. Treatment with insecticides is warranted if trap counts rise above 5 moths/week.

|

table 1. Squash Vine borer Pheromone Trap captures for week ending August 14

|

|

|---|---|

|

Trap location

|

SVB

|

|

Whately

|

1 |

|

North Easton

|

0 |

|

Sharon

|

7 |

|

Westhampton

|

4 |

|

Spray thresholds: Thick-stemmed cucurbits only. 5 moths/week for bush-type cucurbits. 12 moths/week for vining cucurbits.

|

|

Nightshades

Potato virus Y (PVY) was confirmed in tobacco and Yukon Gold potato this week in Hampshire Co. PVY can infect all solanaceous crops and is spread by aphids. Symptoms include leaf streaking, mottling, or mosaic, and in severe cases can cause leaf death, leaf drop, and plant stunting. The virus also causes necrotic flecking and ringspots on potato tubers, which can lead to severe crop losses. Symptoms on potato vary by cultivar, with some varieties showing only mild foliar symptoms while others, especially Dark Red Norland and Yukon Gold, are extremely susceptible and show rugose mosaic symptoms (wrinkly deformation of leaves). Some strains of the virus cause no foliar symptoms in some strains of potato (including Shepody, Silverton Russet, and Russet Norkotah), which contributes to the undetected spread of the disease through fields and seed lots. Infected seed tubers are the most important source of PVY, and seed tubers are certified by state departments of agriculture to ensure little to no virus is present. “Foundation” seed is the best grade and should have less than 0.55% total virus. “Certified” seed can have up to 5% total virus. Resistant potato varieties include Villeta Rose, Eva, Rio, Grande Russet, and Premier Russet. Once aphid populations are high, insecticides are often not effective at controlling PVY via the aphid vector, because the virus is transferred to the plant immediately when an aphid probes into a leaf, and some insecticides increase the rate at which the aphids probe. Aphid repellants such as horticultural oils, and newer behavior modifying pesticides (e.g. Assail, Belay, Admire Pro, Fulfill, Movento, Platinum) may have some efficacy.

Potato virus Y (PVY) was confirmed in tobacco and Yukon Gold potato this week in Hampshire Co. PVY can infect all solanaceous crops and is spread by aphids. Symptoms include leaf streaking, mottling, or mosaic, and in severe cases can cause leaf death, leaf drop, and plant stunting. The virus also causes necrotic flecking and ringspots on potato tubers, which can lead to severe crop losses. Symptoms on potato vary by cultivar, with some varieties showing only mild foliar symptoms while others, especially Dark Red Norland and Yukon Gold, are extremely susceptible and show rugose mosaic symptoms (wrinkly deformation of leaves). Some strains of the virus cause no foliar symptoms in some strains of potato (including Shepody, Silverton Russet, and Russet Norkotah), which contributes to the undetected spread of the disease through fields and seed lots. Infected seed tubers are the most important source of PVY, and seed tubers are certified by state departments of agriculture to ensure little to no virus is present. “Foundation” seed is the best grade and should have less than 0.55% total virus. “Certified” seed can have up to 5% total virus. Resistant potato varieties include Villeta Rose, Eva, Rio, Grande Russet, and Premier Russet. Once aphid populations are high, insecticides are often not effective at controlling PVY via the aphid vector, because the virus is transferred to the plant immediately when an aphid probes into a leaf, and some insecticides increase the rate at which the aphids probe. Aphid repellants such as horticultural oils, and newer behavior modifying pesticides (e.g. Assail, Belay, Admire Pro, Fulfill, Movento, Platinum) may have some efficacy.

Sweet corn

European corn borer (ECB) trap captures remain low and larvae should be controlled by sprays for corn earworm at this point.

Corn earworm (CEW) trap captures are down from last week, with all but one trapping location on a 4-day spray schedule, as we head into the last few plantings of corn.

Fall armyworm (FAW) was caught at 7 out of 15 trapping sites this week, with a high of 26. FAW moths lay eggs in whorl-stage corn, so if you see the ragged feeding damage in whorl corn, plan to apply an insecticide when the tassels in that block have just fully emerged.

Corn leaf aphids (CLA) was observed in sweet corn this week in Franklin Co. CLA is blue-green or black, with black legs. These aphids overwinter as eggs or females on grass weeds and grain crops. When these cereals mature, winged aphids develop and migrate to corn and wild grasses. Both winged and wingless female aphids occur together. Females produce live young (nymphs), which mature in as little as 6 days, resulting in many generations per year. In corn, CLA first colonizes whorl leaves and the immature tassel. Populations may become numerous enough to interfere with pollen shed, stunt plants, and infest layers of the husk with aphids. Maize dwarf mosaic virus may be spread by the corn leaf aphid, though the most important vector for this disease is the green peach aphid. In addition, aphids excrete a sugary liquid called ‘honeydew’, which coats leaves and husks and encourages the growth of sooty mold fungus. The presence of aphids and honeydew on corn husks reduces their marketability. Varieties with purple or green tassels seem less susceptible to aphid build-up than those with yellow tassels. Ample rainfall or irrigation during the silk stage can reduce or eliminate aphid damage. Natural enemies reduce aphid numbers but may not provide adequate control, especially in dry seasons. Whenever possible, conserve predators and parasites by using selective insecticides to control caterpillars. Sweet corn plantings that are seeded before 10 June are generally not bothered by corn leaf aphids. Monitor for aphids while scouting whorl or pre-tassel stage corn for ECB or FAW in July and August. Pre-tassel stage sprays may be needed when 50% of the plants are infested or if 25% have heavy infestations. Sprays applied before 50% of the tassels emerge are more effective than later sprays. CLA outbreaks can be a result of extensive pyrethroid use. Including Lannate or Assail in sprays can help keep aphids under control.

Corn leaf aphids (CLA) was observed in sweet corn this week in Franklin Co. CLA is blue-green or black, with black legs. These aphids overwinter as eggs or females on grass weeds and grain crops. When these cereals mature, winged aphids develop and migrate to corn and wild grasses. Both winged and wingless female aphids occur together. Females produce live young (nymphs), which mature in as little as 6 days, resulting in many generations per year. In corn, CLA first colonizes whorl leaves and the immature tassel. Populations may become numerous enough to interfere with pollen shed, stunt plants, and infest layers of the husk with aphids. Maize dwarf mosaic virus may be spread by the corn leaf aphid, though the most important vector for this disease is the green peach aphid. In addition, aphids excrete a sugary liquid called ‘honeydew’, which coats leaves and husks and encourages the growth of sooty mold fungus. The presence of aphids and honeydew on corn husks reduces their marketability. Varieties with purple or green tassels seem less susceptible to aphid build-up than those with yellow tassels. Ample rainfall or irrigation during the silk stage can reduce or eliminate aphid damage. Natural enemies reduce aphid numbers but may not provide adequate control, especially in dry seasons. Whenever possible, conserve predators and parasites by using selective insecticides to control caterpillars. Sweet corn plantings that are seeded before 10 June are generally not bothered by corn leaf aphids. Monitor for aphids while scouting whorl or pre-tassel stage corn for ECB or FAW in July and August. Pre-tassel stage sprays may be needed when 50% of the plants are infested or if 25% have heavy infestations. Sprays applied before 50% of the tassels emerge are more effective than later sprays. CLA outbreaks can be a result of extensive pyrethroid use. Including Lannate or Assail in sprays can help keep aphids under control.

| Table 2. GDDs & Sweet corn pest trap captures for week ending August 14 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | FAW | CEW | CEW SPRay interval* |

| Western MA | |||||||

| North Adams | 1987 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Richmond | 1803 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| South Deerfield | 2168 | Whately | 5 | 0 | 26 | 20 | 4 days |

| Easthampton | 2084 | Northampton | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Chicopee Falls | 2213 | Granby | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 4 days |

| Granville | 1907 | Southwick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 4 days |

| Central MA | |||||||

| Leominster | 2007 | Leominster | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lancaster | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Northbridge |

2026 |

Grafton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4 days |

| Worcester | 2026 | Spencer | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 4 days |

| Eastern MA | |||||||

| Bolton | 2046 | Bolton | 0 | 1 | 1 | 16.5 | 4 days |

| Stow | 2059 | Concord | 2 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 4 days |

| Lawrence | 2100 | Haverhill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 4 days |

| Ipswich | 2063 | Ipswich | 2 | 0 | 1 | 35 | 4 days |

| Harvard | 2039 | Littleton | 7 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 4 days |

| - | - | Millis | 0 | 4 | n/a | 68 | 4 days |

| Sharon | 2002 | North Easton | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Sharon | 7 | 0 | n/a | 101 | 3 days | ||

| - | - | Sherborn | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4 days |

| Providence, RI | 2078 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | 11 | 50 | 4 days |

| Swansea | 3 | 0 | 8 | 57 | 4 days | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest * If 2+ days above 80°F occur, shorten spray interval by 1 day. ** If CEW trap captures are below 1.4 moths/week, scout block for ECB and FAW caterpillars and make a pesticide application if 12% of plants in a 50-plant sample are infested. |

|||||||

| Table 3. corn earworm spray intervals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Alternaria Leaf Spot in Brassicas

Alternaria leaf spot is the most common disease of brassicas in the Northeast and occurs wherever brassica crops are planted. It can be caused by several fungi in the genus Alternaria, but the species most damaging to vegetable brassica crops are A. brassicae and A. brassicicola. Disease development is favored by cool temperatures and long periods of leaf wetness or high relative humidity. Alternaria leaf spot can be a limiting factor in the production of brassica vegetable and seed crops in regions where these conditions are common. In the Northeast, we usually see Alternaria infections start during humid summer weather and continue into the fall when brassica leaves remain wet for long periods of time due to dew. Infection can cause reduction in crop quality and yield through damage to seedlings, leaves, and heads. Brussels sprouts can be rendered unmarketable by Alternaria lesions on the buds. The disease can spread in storage, so management is especially important for storage crops like cabbage. Crops should be inspected for early symptoms before storing.

The initial symptoms of Alternaria leaf spot are small, black dots surrounded by chlorotic haloes. As the disease progresses, lesions expand into characteristic, dark brown to black circular leaf spots with target-like concentric rings. The centers of lesions often turn brown and crack or fall out, giving the leaf spots a shot-hole appearance. Individual spots coalesce into large necrotic areas and leaf drop can occur. Symptoms typically appear on older, lower leaves first and then move up the plant as the disease progresses. Lesions can develop on cauliflower curds and broccoli heads in addition to the leaves, as well as on petioles and stems.

The initial symptoms of Alternaria leaf spot are small, black dots surrounded by chlorotic haloes. As the disease progresses, lesions expand into characteristic, dark brown to black circular leaf spots with target-like concentric rings. The centers of lesions often turn brown and crack or fall out, giving the leaf spots a shot-hole appearance. Individual spots coalesce into large necrotic areas and leaf drop can occur. Symptoms typically appear on older, lower leaves first and then move up the plant as the disease progresses. Lesions can develop on cauliflower curds and broccoli heads in addition to the leaves, as well as on petioles and stems.

Alternaria species overwinter primarily in diseased crop debris. The pathogen can also survive on seed, both internally and on the seed surface. The main means of introduction into new areas is on infested seed. However, Alternaria fungi produce a profuse amount of airborne spores that can spread easily from field to field and farm to farm within an area once the disease is established. In addition to spreading via wind, spores of Alternaria are spread within fields by splashing water as well as insects, equipment, and workers moving through fields.

Alternaria species overwinter primarily in diseased crop debris. The pathogen can also survive on seed, both internally and on the seed surface. The main means of introduction into new areas is on infested seed. However, Alternaria fungi produce a profuse amount of airborne spores that can spread easily from field to field and farm to farm within an area once the disease is established. In addition to spreading via wind, spores of Alternaria are spread within fields by splashing water as well as insects, equipment, and workers moving through fields.

Spore production is favored by exposure to high humidity (above ~87%) and temperatures between 68 and 86°F. Spores are released during warm, dry periods after a rain. The optimal conditions for new infections are temperatures between 55 and 75°F and high relative humidity or periods of long leaf wetness. Spores produced in the summer heat will proliferate once the weather cools going into the fall.

Cultural Controls

- Buy certified, disease-free seed, or treat seed with hot water to eliminate any Alternaria spores. UMass Extension can treat most brassica seeds. See UMass Hot Water Seed Treatment Service for more information.

- Select disease-tolerant cultivars. There are no cultivars of any brassica that are truly resistant but some cultivars may have characteristics that reduce incidence. In broccoli, look for cultivars with tight, well-domed heads.

- Practice long rotations (at least 3 years) with non-brassica crops.

- Avoid planting succession crops in close proximity to each other and rotate late-season crops to new fields away from early-season brassicas.

- Control brassica weeds, which can serve as alternate hosts.

- Avoid overhead irrigation, especially during broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage head development. Allow sufficient drying time before nightfall if overhead is used.

- Work in young, uninfected plantings first, and older, infected plantings last.

- Incorporate diseased plant debris into the soil immediately after harvest.

- Eliminate cull piles and manage compost piles in order to promptly break down infected crop residues and prevent them from becoming sources of inoculum.

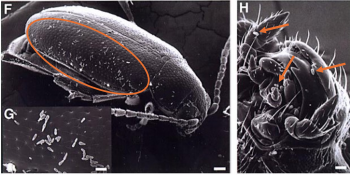

- Control flea beetles, which can spread Alternaria spores as they move through crops. For information on controlling flea beetles, see the article in the May 18, 2023 issue of Veg Notes.

Chemical Control

See Table 1 for recommended fungicides for Alternaria leaf spot and head rot. (The table also includes a column for efficacy of the same materials against downy mildew of brassicas.) The table and associated recommendations are from Christy Hoepting, Cornell Cooperative Extension Vegetable Specialist, based on results from an on-farm trial conducted in 2018 under severe Alternaria pressure. For more information on this trial and an example of an Alternaria fungicide spray program, see Hoepting’s full article in the August 19, 2020 issue of Cornell Veg Edge.

General tips for controlling Alternaria with fungicides:

- Spray fungicides preventively before disease establishes itself because lower frame leaves serve as inoculum to infect heads. Bravo would be an economical choice for preventative applications.

- Once the canopy fills in, aeration is reduced, and leaf wetness is prolonged. Begin application of systemic/translaminar fungicides with very good to excellent activity on Alternaria at this time.

- Use an adjuvant with fungicides that have translaminar or systemic activity for improved efficacy. All fungicides in Table 1 except Bravo are translaminar/systemic.

- Do not apply a copper bactericide in the same tank mix with an adjuvant; excessive leaf burn injury may occur.

- All fungicides listed in Table 1 except Bravo are at risk of contributing to Alternaria developing resistance. See specific product labels for rotation restrictions and seasonal maximum use rates. Be mindful of pre-mixes that have more than one FRAC group per fungicide that need to be managed for fungicide resistance.

Best management practices for avoiding fungicide resistance:

- FRAC 7 fungicides are no longer recommended for control of ALS and head rot.

- FRAC 3 is suspected to be slipping, i.e. ALS is developing resistance to this group.

- Do not apply a product more than 1-2 times before alternating to another FRAC group.

- Do not use more than 2 applications per FRAC group per crop. Bravo is the exception to this, because its multi-site mode of action reduces its risk for fungicide resistance and may be used up to 7 times.

- Save products with short PHIs for close to and during harvest: 0 (Endura, Quadris, Luna Sensation), 1 (Quadris Top) or 3 (Priaxor) days

- Do your fungicide spray program “puzzle” ahead of time. Although there are a lot of fungicide options, it can be tricky to not exceed 2 applications per FRAC per crop, especially when so many products contain premixes of two FRAC groups. It is a good idea to design a 4-week program to use from full canopy fill through harvest. Prior to this, Bravo should suffice. Start with the products that you want to use during harvest with 0 PHI and work backwards to avoid no more than 2 apps per FRAC. Although expensive, Switch (FRAC 9, 12) is an excellent rotation partner.

|

Table 1. Fungicide Recommendations for Controling Alternaria Leaf Spot and Head Rot in Brassicas |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Product |

Active |

FRAC1 Group |

Risk of Fungicide Resistance |

PHI |

Restricted Use2 |

Maximum Use |

Rotation |

Cole Crops on Label3 |

Disease Control |

|

|

Relative Control of ALS4 |

Activity on DM5 |

|||||||||

|

Bravo Weather Stik 1.5 pt (+ other formuations) |

chlorothalonil |

M5 |

Very low |

7 days |

No |

11.7 pts |

None |

ALL |

Mediocre |

Good |

|

Quadris 6-15.5 fl oz (+ other formulation) |

azoxystrobin |

11 |

High |

0 days |

No |

90 fl oz |

None |

ALL |

Good |

Mediocre |

|

Switch 10-14 oz Alterity* 11-14 oz |

cyprodinil + fludioxonil |

9 12 |

Medium |

7 days |

No |

56 oz |

2 |

ALL |

Good |

None |

|

Priaxor 6-8.2 fl oz Everlon* 6-8.2 fl oz |

fluxapyroxad + pyraclostrobin |

7 11 |

Medium-High High |

3 days |

Yes |

24.6 fl oz |

2 |

ALL |

Excellent |

Mediocre |

|

Endura 6-9 oz |

boscalid |

7 11 |

Medium-High |

0 days |

No |

18 fl oz |

2 |

ALL |

Resistance!6 Good |

None |

|

Luna Experience 6-8.6 fl oz |

fluopyram + tebuconazole |

7 3 |

Medium-High Medium |

7 days |

Yes |

34 fl oz (= 4 apps) |

2 |

Brassica leaf greens only |

Caution!6 Mediocre-Good* |

None |

|

Luna Sensation 5-7.6 fl oz |

fluopyram + trifloxystrobin |

7 11 |

Medium-High High |

0 days |

Yes |

15.3 fl oz |

2 |

ALL |

Caution!6 Good |

Mediocre |

|

Luna Flex 10-13.6 fl oz |

fluopyram + difenoconazole |

7 3 |

Medium-High Medium |

1 day |

Yes |

27.2 fl oz (= 2 apps) |

2 |

ALL |

Caution!6 Mediocre-Good |

None |

|

Miravis Prime 11.4 fl oz |

pydiflumetofen + fludioxonil |

7 12 |

Medium-High Low-Medium |

7 days |

Yes |

34.2 fl oz (=3 apps) |

2 |

ALL |

Caution!6 Good |

None |

|

Inspire Super 16-20 fl oz Vango Esq* 14-20 fl oz |

cyprodinil + difenoconazole |

9 3 |

Medium Medium |

7 days |

No |

80 fl oz |

2 |

ALL |

Good-Mediocre |

None |

|

Quadris Top 12-14 fl oz |

azoxystrobin + difenoconazole |

11 3 |

High Medium |

1 day |

No |

56 fl oz |

1 |

ALL |

Excellent |

Not labeled |

|

Viathon 2 pt |

tebuconazole + phosphorous acid |

3 P07 |

Medium Low |

7 days |

No |

8 pt (=4 apps) |

None |

Brassica leaf greens only |

Good |

Good |

|

Topguard EQ 5-8 fl oz |

flutriafol + azoxystrobin |

3 11 |

Medium High |

7 days |

No |

32 fl oz (=4 apps) |

Rotation recommended |

ALL |

Mediocre-Good |

None |

|

Rhyme* 5-7 fl oz |

flutriafol |

3 |

Medium |

7 days |

No |

28 fl oz (=4 apps) |

None |

ALL |

Mediocre-Good |

None |

|

OMRI-Listed: |

||||||||||

|

Oso 5% SC 6.5-13 fl oz |

polyoxin D zinc salt |

19 |

Medium |

0 days |

No |

78 fl oz (=6 apps) |

None |

ALL |

Mediocre |

None |

|

Kocide 3000-O 0.5-0.75 lb7 |

copper hydroxide |

M1 |

Low |

0 days |

No |

8.8 lb (=11 apps) |

None |

ALL |

Mediocre-Poor |

Labeled** |

|

Cueva 0.5% v/v7 |

copper octanoate |

M1 |

Low |

0 days |

No |

13.25 qt (=2 apps) |

Rotation recommended |

ALL |

Mediocre-Poor |

Labeled** |

|

1FRAC: Fungicide Resistance Action Committee group. Fungicides that belong to the same FRAC group are at risk for developing cross-resistance. For best fungicide resistance management practices, fungicides belonging to different FRAC groups should be rotated. |

||||||||||

--Written by UMass Extension Vegetable Program. Chemical recommendations from Fungicide "Cheat Sheet" for Alternaria Leaf Spot and Head Rot in Broccoli and Other Cole Crops, 2024, by Christy Hopeting, Cornell Cooperative Extension, updated August 2024.

Late Season Cover Crops

There are many reasons to plant a late season cover crop. Generally, a late season cover crop will increase organic matter, improve soil structure, scavenge remaining nutrients, choke out weeds, and prevent soil erosion. There are several types of grasses, legumes, and brassicas that work well as winter cover crops, and each have their own strengths and weaknesses. Below we’ve described several good choices, depending on your specific goals and field conditions. These species do best when planted in late summer or early fall (see individual entries below for more details). While the fall planting window has extended, in some cases into November (!), remember that all cover crops are most effective when planted as quickly as possible following harvest.

Grasses

Grass cover crops can reduce erosion, absorb soil nitrogen (N), and produce a significant amount of organic matter. Kill grasses before maturity in the spring to ensure efficient decomposition. Mix grass species with a legume to reduce the C:N ratio and supply more N for the following year’s crop, or with any broadleaf species to increase weed suppression.

Winter or cereal rye (Secale cereale) is the most common cover crop used by growers in Massachusetts. It is inexpensive, readily available, easy to establish, and can be seeded up until 2 weeks before a killing frost. November-planted rye is more practically thought of as a very-early-planted spring cover crop since it will grow little until the spring. Rye is best planted before September 15 to recover the available N from the soil, produce enough canopy to outcompete weeds, and protect the soil from erosion. It consistently overwinters here and will continue to grow in the spring, producing up to 7,000 lbs/A of biomass to contribute to soil organic matter. It should be killed before the flowers emerge or be seeded with a legume to keep the C:N ratio low and prevent N tie-up . It can take several weeks and multiple tillage passes to break down in the spring, so it is best used in fields that will be planted into a late spring/early summer crop next year. Seeding rate: 90-120 lbs/A broadcast; 60-100 lbs/A drilled; 50-60 lbs/A mixed with a legume.

Annual or Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) are also gaining popularity in the Northeast. These grasses have dense root systems that outcompete weeds, protect against erosion, and are easy to incorporate in the spring. Annual ryegrass can tolerate some flooding. Perennial ryegrass is more cold-hardy but also harder to kill if it goes to seed. Both ryegrasses are good for interseeding since they are shade and traffic tolerant, but may not germinate very well under dry conditions. Plant 6-8 weeks before the fall frost date. The seed is small and light, so specialized equipment such as a Brillion seeder is needed to seed a large area. Seeding rate: 20-30 lbs/A broadcast; 10-20 lbs/A drilled; 8-15 lbs/A mixed with a legume.

Oats (Avena sativa) come up quickly and can be seeded in late summer. They are best planted before September 15, similar to winter rye. Unlike winter rye, oats will winterkill in Massachusetts, making for simpler field preparation in the spring. However, oats provide less weed control, lower organic matter contribution, and do not contribute N to the following crop in the spring. Mixing with an overwintering legume, such as hairy vetch, can produce N without the timing complications of killing a mixed cover crop stand in the spring. Seeding rate: 110-140 lbs/A broadcast; 80-110 lbs/A drilled; 60-90 lbs/A mixed with a legume.

Oats (Avena sativa) come up quickly and can be seeded in late summer. They are best planted before September 15, similar to winter rye. Unlike winter rye, oats will winterkill in Massachusetts, making for simpler field preparation in the spring. However, oats provide less weed control, lower organic matter contribution, and do not contribute N to the following crop in the spring. Mixing with an overwintering legume, such as hairy vetch, can produce N without the timing complications of killing a mixed cover crop stand in the spring. Seeding rate: 110-140 lbs/A broadcast; 80-110 lbs/A drilled; 60-90 lbs/A mixed with a legume.

Winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) is increasingly being used both as a cereal grain and as a cover crop. It is winter hardy, but does not grow as tall or mature as quickly as rye so there is no rush to kill it in early spring and risk compacting wet soils. Wheat is excellent for erosion control, scavenging N, P, and K, building soil organic matter, and improving tilth. For best results, plant it in late summer to early fall, before September 15. Best growth will be in well-drained soils with moderate fertility. Rye is a better choice on wet soils. Wheat works well as a companion crop for legumes, such as hairy vetch or crimson clover, because they all mature at the same time in the spring. Seeding rate: 90-120 lbs/A broadcast; 60-100 lbs/A drilled; 60-90 lbs/A mixed with a legume.

Triticale (x Triticosecale) is a hybrid between wheat and rye. It can be seeded as early as August or as late as late October and can produce more fall growth than winter wheat, providing more weed suppression and erosion control. Seeding rate: 90-100 lbs/A broadcast; 75-80 lbs/A drilled; 60-90 lbs/A mixed with a legume.

Legumes

Legume cover crops are a good choice if you are interested in adding N to the soil and reducing your nitrogen fertility bill. Legumes fix N from the air and store it in their leaves and then roots during the winter. That N is made available to plants when the legume is tilled in and starts to decompose in the soil. It's a good idea to inoculate seed with the appropriate N-fixing bacteria before planting. Bacterial inoculants are specific to closely related legumes (you'll most commonly see them separated into clover/alfalfa and pea/vetch groupings). Regular use of the same types of cover crops may establish bacterial populations in the soil but most growers add inoculants annually since they are essential to N fixation and affordable. If well-managed, legume cover crops can provide as much as 100-150 lbs N/A to the following crop.

Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) benefits from growing with a nurse crop such as rye or wheat to help reduce matting during the spring and to keep weeds down. The vetch and the grain can be mixed together in the seed drill or broadcast seeder. A vetch + grass cover crop mixture retains more soil moisture than a grass planted alone. In the spring, incorporate vetch at early bloom, typically in late May. Vetch seeded in early August is less likely to survive the winter. With a good flail mower, vetch can be used in a reduced tillage system without matting and tangling in the equipment. Seeding rate: 25-40 lbs/A broadcast; 15-40 lbs/A drilled, 15-20 lbs/A mixed with a grass.

Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) benefits from growing with a nurse crop such as rye or wheat to help reduce matting during the spring and to keep weeds down. The vetch and the grain can be mixed together in the seed drill or broadcast seeder. A vetch + grass cover crop mixture retains more soil moisture than a grass planted alone. In the spring, incorporate vetch at early bloom, typically in late May. Vetch seeded in early August is less likely to survive the winter. With a good flail mower, vetch can be used in a reduced tillage system without matting and tangling in the equipment. Seeding rate: 25-40 lbs/A broadcast; 15-40 lbs/A drilled, 15-20 lbs/A mixed with a grass.

Red clover (Trifolium pratense) is a short-lived perennial that is somewhat tolerant of soil acidity and poor drainage. Mammoth red clover produces more biomass for plow-down than medium red clover but does not regrow as well after mowing. Mammoth will often establish better than medium red clover in dry or acidic soils. Sow in early spring or late summer. Red clover can be undersown in mid-summer into corn or winter squash before it vines, and into other crops such as fall brassicas if soil moisture is plentiful. Clovers germinate and grow slowly and so can be planted along with a faster-growing grass and/or peas as a nurse crop. Clovers are a good option to include in a field that won’t be planted into a cash crop for a full year or more. Seeding rate: 10-15 lbs/A broadcast; 6-15 lbs/A drilled; 6-10 lbs/A mixed with a grass.

Crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum) grown as a winter annual should be seeded early August to early September in New England; seed it too early and it will make seeds in the fall. While it grows well in dry conditions, it may have trouble germinating. This clover is a better fall weed suppressor than hairy vetch. Crimson clover is easily killed by incorporation or can even be rolled or mowed in the spring at late-bloom stage for no-till operations. It will germinate faster than other clovers. Seeding rate: 22-30 lbs/A (15-20 lbs/A in a mixture) broadcast; 15-18 lb/A (10-12 lbs/A in a mixture) drilled.

Crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum) grown as a winter annual should be seeded early August to early September in New England; seed it too early and it will make seeds in the fall. While it grows well in dry conditions, it may have trouble germinating. This clover is a better fall weed suppressor than hairy vetch. Crimson clover is easily killed by incorporation or can even be rolled or mowed in the spring at late-bloom stage for no-till operations. It will germinate faster than other clovers. Seeding rate: 22-30 lbs/A (15-20 lbs/A in a mixture) broadcast; 15-18 lb/A (10-12 lbs/A in a mixture) drilled.

Balansa clover (Trifolium michelianum) is a winter-hardy annual clover with smaller seeds than crimson clover. It grows slowly in the fall and is best grown with a nurse crop like oats. Hollow stems make balansa clover more suitable for spring roller crimping than other legumes. Seeding rate: 10-15 lbs/A broadcast; 6-15 lbs/A drilled; 6-10 lbs/A mixed with a grass.

Peas (Pisum sativum subsp. arvense) come in two main types: Austrian winter peas (black peas) and Canadian field peas (spring peas). Both can be planted mid-August to mid-September in much of New England. These peas fix N more quickly in dry conditions than white clover, crimson clover, or hairy vetch but winterkilled "spring" field peas will not produce a nitrogen credit for spring crops. Peas are susceptible to Sclerotinia so don’t plant them in a field with a history of white mold. Drill or incorporate seed 1-3 inches deep to ensure good soil moisture contact. Seeding rate: 80-120 lbs/A broadcast; 75-100 lbs/A drilled; 60-80 lbs/A in a mix.

Brassicas

Brassicas are used as cover crops for pest management or, in the case of the tillage radish, for improving water drainage and soil structure. Brassica cover crop species are susceptible to the same pests as brassica cash crops, so be sure to factor in any brassica cover crops that you plant when planning crop rotations for pest management.

Tillage radish (Raphanus sativus) is also known as daikon, forage, or oilseed radish. Tillage radishes act as biological subsoilers as their taproots can grow to 8-14 inches long. With its deep roots, this cover crop can recover P, S, Ca, and B for the following season, but a cash crop must be planted early in the spring or else these nutrients are lost through fast decomposition and the deep root holes. Best planted in late August, this cover crop typically winterkills in November or December. A unique no-till strategy with forage radish includes seeding it in the late summer along with cover crop mixtures on 6-ft. centered beds, then in the spring, place transplant plugs directly in the holes where the radishes grew. This cover crop releases most of its scavenged N in winter and early spring, but growing with a hardy grass like rye can recapture the N released by radish decomposition. Higher seeding rates are effective for weed management, while lower seeding rates are better for breaking compaction. Seeding rate: 10-13 lbs/A broadcast; 7-10lbs/A drilled; 5-8 lbs/A in a mixture.

Brown mustard (Brassica juncea) found in many of the ‘Caliente’ seed mixes is a biofumigant planted to combat root-knot nematode and a variety of soil-borne fungal pathogens, including Fusarium, Verticillium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium, and Phytophthora capsici. It is also allelopathic against weeds. If allowed to flower, this crop is highly attractive to honeybees. Successful biofumigation with this cover crop is achieved by following these steps:

Brown mustard (Brassica juncea) found in many of the ‘Caliente’ seed mixes is a biofumigant planted to combat root-knot nematode and a variety of soil-borne fungal pathogens, including Fusarium, Verticillium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium, and Phytophthora capsici. It is also allelopathic against weeds. If allowed to flower, this crop is highly attractive to honeybees. Successful biofumigation with this cover crop is achieved by following these steps:

- Apply adequate fertility (50 lbs N/A and 20 lbs S/A).

- Allow it to flower before incorporation.

- Mow and disc or rototill under and roll or pack the soil immediately.

- Irrigate after incorporation or incorporate before rain to enhance fumigation.

Plant brown mustard in late August through September. Seeding rate: 10-15lbs/A broadcast; 8-12 lbs/A drilled.

It is always better to plant a cover crop, regardless of the type, than leave a field bare; leaving a field bare over the winter is very damaging to soil structure and will increase erosion and reduce long-term fertility. Though it may take several growing seasons or a lifetime to perfect the art of cover cropping, your soil will thank you.

Resources:

- Northeast Cover Crops Council Cover Crop Explorer and Species Selector Tool.

- A Comprehensive Guide to Cover Crop Species Used in the Northeast United States. Prepared by USDA-NRCS.

- Managing Cover Crops Profitably. 3rd ed. Published by the Sustainable Agriculture Network, Beltsville, MD.

- Cover Crop Plant Guides prepared for USDA by NRCS, RMA and FSA.

- Cover Crop Chart prepared by USDA-ARS.

--UMass Veg Program. Revised for 2024 by Arthur Siller.

Fruit Rots of Pumpkins & Winter Squash

While this summer wasn’t disastrously wet like last year, we had our share of rain, often in big bursts that resulted in saturated fields and then lots of Phytophthora blight. Phytophthora blight is always a top concern in winter squash, but the other diseases in this article can lead to significant losses as well. Take note of what diseases are present in your squash and pumpkin crops this fall to inform crop rotations and management for next year.

Many types of pathogens—fungi, bacteria, and viruses—can cause fruit rots, spots, and other abnormalities in pumpkins and winter squash that render them unmarketable. The most common rots, which happen to be caused by fungi (and one fungal-like organism), will be discussed below. Most of these fruit-rotting pathogens also affect the foliage, so controlling the disease on the leaves can reduce the amount of inoculum present to infect fruit later in the season. For descriptions of foliar symptoms and tips for managing these diseases on the foliage see the July 27, 2023 issue of Veg Notes and for chemical recommendations, please see the pumpkin and squash disease section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide.

Phytophthora Blight (Phytophthora capsici, an oomycete pathogen)

Phytophthora Blight (Phytophthora capsici, an oomycete pathogen)

Perhaps the most serious fruit rot in wet years, infection by Phytophthora begins as a water-soaked or sunken spot, most often occurring at the site of fruit contact with the soil, since that is where the pathogen is spreading from. As the rot develops, a mass of powdery white sporangia will develop in the water-soaked spot and will continue to spread, eventually covering the entire fruit. The pathogen survives in the soil for many years—the exact duration is not known, but a reasonable estimate is 8-10 years. Disease can develop and spread rapidly when soil moisture is high and temperatures are between 80-90°F. Entire fields may be destroyed very quickly.

Tips for managing Phytophthora blight

Manage soil moisture by sub-soiling and avoiding over-irrigating. Select well-drained fields and avoid areas of fields that do not drain well. Destroying diseased areas plus a buffer of healthy plants at the start of an outbreak can be effective in slowing the spread of disease. Reduced- and no-till production has been shown to greatly increase soil drainage capacity and help manage Phytophthora blight. Biofumigation with ‘Caliente’ mustard can reduce inoculum in the soil. There are no squash or pumpkin varieties that are resistant to Phytophthora blight; pumpkins with hard, gourd-like rinds may hold up better in the field in general but are not resistant to the disease. Oomycete-specific fungicides can be effective in reducing severity of Phytophthora blight in squash and other hosts such as peppers and tomatoes, if applied early and regularly. For full recommendations on managing Phytophthora blight, see the article in the July 13, 2023 issue of Veg Notes.

Fusarium Fruit Rot (Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae)

Fusarium Fruit Rot (Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae)

Fusarium is another soil-borne pathogen that attacks squash and pumpkin fruits at the soil line. Surfaces of fruit that are in contact with the soil develop tan to brown, firm, dry, sunken lesions which may occur in concentric rings and remain firm unless invaded by secondary organisms. Severity of infection varies with soil moisture and the age of the rind when infection occurs—younger fruit is more susceptible to severe rot. Fusarium can survive in seed but does not affect the germination or viability of the seed. This pathogen produces abundant overwintering structures (chlamydospores), but these only survive in the soil for 2-3 years. Cultivars vary in their resistance, with larger pumpkins generally being more susceptible.

Black Rot (Didymella bryoniae)

Black Rot (Didymella bryoniae)

This disease produces a distinctive black decay on squash and pumpkin fruit. Initially, a brown to pink, water-soaked area develops, in which numerous, black fruiting bodies (pycnidia) are embedded. Black rot on butternut may look very different than on other squashes; on butternut it may appear as a superficial, hardened, tan to white area which can develop concentric rings. Large Halloween pumpkins are more susceptible to black rot than smaller pie types. The pathogen is soil- and seed-borne and can overwinter in infected crop debris as dormant mycelium or chlamydospores. Wounding is not required for disease initiation, but striped cucumber beetle or aphid feeding and powdery mildew infection all lead to increased susceptibility. This disease is called gummy stem blight when it infects cucurbit leaves and stems. Controlling powdery mildew can significantly reduce black rot infection of pumpkins. For recommendations for chemical control of powdery mildew, see the https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/newsletters/vegetable-notes/vegetable-notes-2024-vol-368#dm-pm.

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum orbiculare)

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum orbiculare)

Cucurbit anthracnose is common on the fruit and foliage of watermelons, squash, melons, and cucumbers in humid regions. Young fruit may turn black and die if their pedicels are infected, while older fruit develop circular, noticeably sunken, dark green to black lesions which may produce a salmon colored exudate under moist conditions. In addition to the lesions, infected fruit may have a bitter or off-taste. Infected fruits can deteriorate quickly due to the invasion of secondary rot organisms. C. orbiculare can be seed-borne and also survives between crops in infected crop debris, volunteer plants, and weeds in the cucurbit family. It is spread by splashing water, workers, and tools in warm, humid weather.

Scab (Cladosporium cucumerinum)

Scab (Cladosporium cucumerinum)

Scab can affect all parts of cucurbit plants, but is a concern primarily because of the disfiguring scabby lesions that develop on fruit. The disease is favored by heavy fog, heavy dews, or light rains, and temperatures at or below 70°F. The spores are produced in long chains and are easily dislodged and spread long distances by wind. On foliage, the first sign of the disease is pale-green, water-soaked lesions which turn gray and become angular as they are contained by leaf veins. On fruit, spots first appear as small sunken areas which can be mistaken for insect injury. The spots may ooze a sticky liquid and become crater-like as they darken with age. Dark green, velvety layers of spores may appear in the cavities and secondary soft-rotting bacteria can invade. Severity of symptoms varies with the age of the fruit when it becomes infected. C. cucumerinum overwinters in infected crop debris and soil, and may also be seed-borne. Spores produced in the spring can infect in as little as 9 hours, produce spots within 3 days, and produce a new crop of spores within 4 days.

Plectosporium Blight (Plectosporium tabacinum)

Plectosporium Blight (Plectosporium tabacinum)

Plectosporium blight affects many plant parts but is most damaging when it affects cucurbit fruit. Pumpkins, yellow squash, and zucchini are the most susceptible. Plectosporium lesions are white to tan; on stems and leaf veins, they are elongate and boat-shaped (imagine a bird’s-eye-view of a canoe), while leaf and fruit lesions are more rounded. Severe stem and petiole infections cause leaves to become brittle and can result in death of leaves and defoliation. On fruit, the pathogen causes white, tan, or silvery russeting; individual lesions can coalesce to form a continuous scabby layer. Plectosporium blight is favored by wet weather; in wet years, crop losses in no-spray and low-spray fields can range from 50 to 100%. No resistant cultivar of pumpkins has been reported. It is not known to be seed-borne.

Management of Fungal Fruit Rots:

-

Start with disease-free seed or use fungicide-treated seed. Cucurbit seeds cannot be treated with hot water to eliminate pathogens because the seeds are too large for the heat to penetrate quickly enough.

-

Do not save your own seed if disease is present in the field.

-

Select well-drained fields with good air circulation to promote rapid drying of foliage and fruit.

-

Rotate out of cucurbits for 2 or more years.

-

Fungicide sprays can reduce diseases which start in the foliage and then splash on the fruit e.g. Plectosporium blight, scab, and anthracnose. To effectively control disease, applications must begin before or just as symptoms begin to develop and must be made regularly.

-

Destroy and plow crop residues promptly after harvest to prevent their spreading and hasten their breakdown in the soil.

-

Avoid chilling injury to winter squash and pumpkins in storage, as this can allow for spread of some diseases in storage. Store fruit at 50-55°F and ~60% relative humidity. For information on curing and storage conditions for pumpkins and winter squash, see the September 14, 2023 issue of Veg Notes.

—M. Bess Dicklow, UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab (retired)

News

39th Massachusetts Tomato Contest This Tuesday August 20th

The 39th Annual Massachusetts Tomato Contest will be held at the Boston Public Market on Tuesday, August 20th. Tomatoes will be judged by a panel of experts on flavor, firmness/slicing quality, exterior color and shape. Growers can bring tomatoes to the Boston Public Market between 8:45am and 10:45am on August 20th or drop their entries off with a registration form to one of the regional drop-off locations on Monday, August 19th. Drop off locations include sites in South Deerfield, Southboro, North Easton and West Newbury. These tomatoes will be brought to Boston on Tuesday.

For complete details, including drop off locations, contest criteria, and a registration form, click here. Be sure to include the registration form with all entries.

Questions? Please contact David Webber, David.Webber@mass.gov.

Call for Comments for Potential Mancozeb Registration Changes

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released their proposed interim registration review decision for mancozeb in July 2024. Mancozeb is a multisite mode of action fungicide used for the prevention and control of fungal pathogens in fruit and vegetable crops, ornamental plants, and turf grass.

There is an open comment period for the public to provide responses to the proposed risk mitigation revisions and how they could impact production. The comment period ends on September 16, 2024. To view the amended proposed interim registration review in its entirety, see Docket No. EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0291 at www.regulations.gov. For instruction on how to submit comments, visit https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/07/17/2024-15650/pesticide-registration-review-proposed-decisions-for-several-pesticides-notice-of-availability-and.

Proposed changes relevant to vegetable crops include new spray-drift reduction measures, new personal protective equipment requirements and engineering controls, spray drift management measures, and changes to REIs (broccoli, cabbage to 6 days; pepper, tomato, and cucurbit to 3 days). The proposed revisions also include several use terminations, including all uses in grapes. Rutgers Cooperative Extension has provided a good summary of all of the proposed changes here.

Events

Bees and Beyond: Pollinators at the Arboretum

When: This Saturday! August 18, 2:00-3:30pm

Where: Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130

Registration: Free. Registration is required. Click here to register.

Join pollinator expert and UMass Extension educator Nicole Bell for a walk through the Arboretum’s meadows to find bees and other pollinators in their natural habitat. Nicole will use a sweep net to find and catch bees in the landscape so participants can see them up close, while we talk about the most common bees found in Massachusetts, where they live and what they eat, and the importance of places like the Arboretum for pollinator conservation.

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health - South Deerfield, MA

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Save the Date! Gaining Ground Farm Tour

When: Thursday, October 17, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Gaining Ground, 341 Virginia Rd., Concord, MA 01742

Join New Entry and UMass Extension for a farm tour of Gaining Ground Farm in Concord, MA!

Registration and event details coming soon.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.