To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Crop Conditions

The weather has been remarkably nice for a few weeks, and things are chugging along. We’re starting to see more bacterial diseases develop, though, as a result of the hot and humid weather a few weeks ago—see pest alerts and the bacterial diseases article in this issue for lots more information on those. Cucumbers and squash and zucchini are flooding in, and fresh onions are sizing up. Field tomatoes are loaded with green fruit, and peppers are starting to make fruit too. Sweet corn is out on stands, a week early, and garlic harvest is fast approaching!

The weather has been remarkably nice for a few weeks, and things are chugging along. We’re starting to see more bacterial diseases develop, though, as a result of the hot and humid weather a few weeks ago—see pest alerts and the bacterial diseases article in this issue for lots more information on those. Cucumbers and squash and zucchini are flooding in, and fresh onions are sizing up. Field tomatoes are loaded with green fruit, and peppers are starting to make fruit too. Sweet corn is out on stands, a week early, and garlic harvest is fast approaching!

It's been so nice to see so many of you at our twilight meetings so far this summer. We’ll be at Astarte Farm in Hadley next Tuesday, to talk about pollinator habitat and cut flower production—we hope you can join us! See the events section or click HERE for more information and to register.

Pest Alerts

Basil

Basil downy mildew (BDM) was confirmed in Hampshire Co. today, on Spicy Globe basil. This is fairly early to see BDM in MA. If you grow later successions of basil, now is a good time to switch to planting resistant varieties, if you haven’t already. Growing resistant varieties starting in July is the best management practice. Based on varietal responses in UMass trials, a recommended combination is to grow Prospera and Passion, and then introduce the new Prospera Active (which contains a 2nd BDM resistance gene in addition to the gene in the original Prospera) later in the season. Conventional growers can increase their protection with fungicides. Effective materials include Quadris, Reason, Revus, Orondis Gold, Orondis Opti, Ranman, and phosphorous acid fungicides. For more information on BDM-resistant basil varieties and labeled fungicides, see our article in the December 14, 2023 issue. Let us know (umassveg@umass.edu) if you see downy mildew on any of the resistant varieties this summer so that we can help track the evolution of this important pest.

Brassicas

Black rot is developing now in brassica crops, after the rain, heat, and humidity of the last few weeks. Black rot is caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. The pathogen is most often introduced into fields on seed, and then moves throughout fields via splashing water, wind, equipment, people, and insects. The bacteria enter the plant through insect feeding damage or other wounds and also through hydathodes—the tiny pores at the edges of the leaf that occur where the leaf veins end. Infected areas turn yellow then brown, and the veins often turn black. When infection occurs through hydathodes, characteristic V-shaped lesions develop at the edges of the leaves. If you have black rot in one brassica crop, slow the spread by working in clean fields before working in the infected crop. Incorporate infected crop residues promptly after harvest, and practice a 3-year crop rotation out of brassicas. Seed can be treated with hot water to eliminate the bacteria. Copper products can prevent the development of black rot if applied before plants are infected and with continued sprays at 7- to 10-day intervals after symptoms develop.

Black rot is developing now in brassica crops, after the rain, heat, and humidity of the last few weeks. Black rot is caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. The pathogen is most often introduced into fields on seed, and then moves throughout fields via splashing water, wind, equipment, people, and insects. The bacteria enter the plant through insect feeding damage or other wounds and also through hydathodes—the tiny pores at the edges of the leaf that occur where the leaf veins end. Infected areas turn yellow then brown, and the veins often turn black. When infection occurs through hydathodes, characteristic V-shaped lesions develop at the edges of the leaves. If you have black rot in one brassica crop, slow the spread by working in clean fields before working in the infected crop. Incorporate infected crop residues promptly after harvest, and practice a 3-year crop rotation out of brassicas. Seed can be treated with hot water to eliminate the bacteria. Copper products can prevent the development of black rot if applied before plants are infected and with continued sprays at 7- to 10-day intervals after symptoms develop.

Cabbage aphids were observed in low levels on broccolini this week in Hampshire Co. Cabbage aphids are green but covered in a waxy powder that makes them look gray. They are particularly damaging in Brussels sprouts when they infest the sprouts. Often, the first sign of infestation is small areas of blotchy yellowing on the top sides of leaves, opposite an aphid colony on the underside of the leaf. Scout weekly and treat if 10% of plants are infested. Include a spreader-sticker in all sprays unless the label prohibits it, to help materials adhere to the waxy leaves. Avoid the use of broad-spectrum insecticides that will also kill the beneficial insects that help keep aphid populations in check. Recommended conventional materials include Movento, Fulfill, Beleaf, Assail, and Admire Pro. The most effective materials for organic growers is a tank mix of insecticidal soap (e.g., M-Pede), azadirachtin (many products), and pyrethrins (e.g., Pyganic). Horticultural oils (e.g., JMS Stylet Oil, Suffoil X) will also work to smother the aphids. Control must start when populations are low.

Cabbage aphids were observed in low levels on broccolini this week in Hampshire Co. Cabbage aphids are green but covered in a waxy powder that makes them look gray. They are particularly damaging in Brussels sprouts when they infest the sprouts. Often, the first sign of infestation is small areas of blotchy yellowing on the top sides of leaves, opposite an aphid colony on the underside of the leaf. Scout weekly and treat if 10% of plants are infested. Include a spreader-sticker in all sprays unless the label prohibits it, to help materials adhere to the waxy leaves. Avoid the use of broad-spectrum insecticides that will also kill the beneficial insects that help keep aphid populations in check. Recommended conventional materials include Movento, Fulfill, Beleaf, Assail, and Admire Pro. The most effective materials for organic growers is a tank mix of insecticidal soap (e.g., M-Pede), azadirachtin (many products), and pyrethrins (e.g., Pyganic). Horticultural oils (e.g., JMS Stylet Oil, Suffoil X) will also work to smother the aphids. Control must start when populations are low.

Cucurbits

Angular leaf spot: We received another diagnosis of angular leaf spot this week in pumpkin. This disease is often introduced into a crop via seed and is then spread plant to plant by splashing rain or runoff, or insects or workers moving through the field. Symptoms begin as small, round, water-soaked spots, which expand until they are confined by veins, giving the characteristic angular look. The spots dry out and turn yellow-brown, and the dead tissue may fall out of the center, leaving a “shot-hole” appearance. If caught early in the field, copper may be effective in reducing the spread of angular leaf spot.

Angular leaf spot: We received another diagnosis of angular leaf spot this week in pumpkin. This disease is often introduced into a crop via seed and is then spread plant to plant by splashing rain or runoff, or insects or workers moving through the field. Symptoms begin as small, round, water-soaked spots, which expand until they are confined by veins, giving the characteristic angular look. The spots dry out and turn yellow-brown, and the dead tissue may fall out of the center, leaving a “shot-hole” appearance. If caught early in the field, copper may be effective in reducing the spread of angular leaf spot.

Nightshades

Pepper maggot flies will be emerging soon. If you have this pest on your farm, it’s time to start monitoring. Pepper maggot flies lay their eggs in the flesh of pepper fruit. The resulting maggot feeds inside the pepper then drops to the soil to pupate. Infested fruit often develop secondary rots. The simplest way to monitor for pepper maggot is to scout for the oviposition scars—small, dimpled marks left by the egg-laying females. Cherry peppers are a preferred host and can be planted in border rows for easy monitoring. As soon as oviposition marks are observed, apply an insecticide. Insecticides need to target the adult flies because the larvae are protected from pesticides inside the fruit. Labeled materials include alpha-cypermethrin (e.g. Fastac), dimethoate, malathion, zeta-cypermethrin (e.g. Mustang), and spinosad (e.g., GF-120 Naturalyte, which is labeled for organic use). Infested fruit should be removed from the field promptly and destroyed—make sure the larvae are not able to complete their life cycle in infested fruit in a cull pile. Using plastic mulch and weed mat as soil barriers should prevent the larvae from reaching the soil to pupate.

Pepper maggot flies will be emerging soon. If you have this pest on your farm, it’s time to start monitoring. Pepper maggot flies lay their eggs in the flesh of pepper fruit. The resulting maggot feeds inside the pepper then drops to the soil to pupate. Infested fruit often develop secondary rots. The simplest way to monitor for pepper maggot is to scout for the oviposition scars—small, dimpled marks left by the egg-laying females. Cherry peppers are a preferred host and can be planted in border rows for easy monitoring. As soon as oviposition marks are observed, apply an insecticide. Insecticides need to target the adult flies because the larvae are protected from pesticides inside the fruit. Labeled materials include alpha-cypermethrin (e.g. Fastac), dimethoate, malathion, zeta-cypermethrin (e.g. Mustang), and spinosad (e.g., GF-120 Naturalyte, which is labeled for organic use). Infested fruit should be removed from the field promptly and destroyed—make sure the larvae are not able to complete their life cycle in infested fruit in a cull pile. Using plastic mulch and weed mat as soil barriers should prevent the larvae from reaching the soil to pupate.

Bacterial leaf spot (BLS) was reported on pepper this week. BLS symptoms start as small yellow-green specks that expand during favorable weather and coalesce into large dark streaks. BLS can occur on tomato or pepper and will infect fruit of both crops as well. There are 11 strains (0-10) of the BLS pathogen (Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatora)—some strains infect only pepper, some infect only tomato, and some can infect both. Pepper cultivars are available with BLS resistance, however they are usually resistant to specific races of the pathogen, so controlling this disease with resistant varieties effectively requires knowing what races of the pathogen are likely to be present. X10R™ varieties provide intermediate resistance to all strains. Copper products are the most effective, and the addition of mancozeb products (e.g. Penncozeb, Manzate, Dithane, Roper) can increase their efficacy. ManKocide is a pre-mix of mancozeb and copper.

Bacterial leaf spot (BLS) was reported on pepper this week. BLS symptoms start as small yellow-green specks that expand during favorable weather and coalesce into large dark streaks. BLS can occur on tomato or pepper and will infect fruit of both crops as well. There are 11 strains (0-10) of the BLS pathogen (Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatora)—some strains infect only pepper, some infect only tomato, and some can infect both. Pepper cultivars are available with BLS resistance, however they are usually resistant to specific races of the pathogen, so controlling this disease with resistant varieties effectively requires knowing what races of the pathogen are likely to be present. X10R™ varieties provide intermediate resistance to all strains. Copper products are the most effective, and the addition of mancozeb products (e.g. Penncozeb, Manzate, Dithane, Roper) can increase their efficacy. ManKocide is a pre-mix of mancozeb and copper.

Sweet Corn

European corn borer trap captures are low this week, as the first flight wraps up. The 2nd flight starts at 1400 GDDs, which should be in the next few weeks, but caterpillars are still feeding in tassels and ears. A good time to apply a pesticide is when tassels have just fully emerged, to catch the caterpillars before they migrate down from the whorl and tassels into the ears. Treat if 12% of plants are infested.

Corn earworm trap counts are lower this week in general, with moth captures at several locations not warranting any spray. If CEW trap captures are below 1.4/week, scout silking corn for ECB caterpillars and treat at the 12% threshold.

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | FAW | CEW | CEW SPRay interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western MA | |||||||

| North Adams | 1028 | n/a | - | - | - | - | - |

| Richmond | 884 | n/a | - | - | - | - | - |

| South Deerfield | 1097 | Whately | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chicopee Falls |

1129 |

Granby | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| Granville | 940 | Southwick | - | - | - | - | - |

| Central MA | |||||||

| Leominster |

980 |

Leominster | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lancaster | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | no spray* | ||

| Northbridge | 1003 | Grafton | - | - | - | - | - |

| Worcester | 999 | Spencer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | no spray* |

| Eastern MA | |||||||

| Bolton | 992 | Bolton | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | no spray* |

| Stow | 1006 | Concord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 days |

| Ipswich | 979 | Ipswich | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 days |

| Harvard | 969 | Littleton | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | no spray* |

| - | - | Millis | 0 | - | n/a | 0 | no spray* |

| Sharon | 964 | North Easton | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sharon | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| - | - | Sherborn | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | no spray* |

| Providence, RI | 1014 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| Swansea | - | - | - | - | - | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest * If CEW trap captures are below 1.4 moths/week, scout block for ECB and FAW caterpillars and make a pesticide application if 12% of plants in a 50-plant sample are infested. |

|||||||

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Bacterial Diseases of Vegetable Crops

We are seeing lots of bacterial diseases popping up after the hot then wet weather a few weeks ago. Bacterial pathogens thrive in hot, humid weather, so this is not a surprise.

Plant pathogenic bacteria can generally be divided into two categories: leaf spots and blights, and vascular pathogens.

Bacterial leaf spot and blight diseases are most often caused by species of Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas and tend to begin as small water-soaked spots that eventually turn brown. A yellow halo may or may not be present around the spots. In severe cases, spots can coalesce and destroy entire leaves. Because bacterial infection of the leaf tissue is limited by leaf veins, bacterial leaf spots are often angular in shape; however, this may not always be the case, and non-bacterial pathogens such as the downy mildews can also cause angular leaf spots.

These are the most common bacterial leaf spot diseases in vegetables:

- Bacterial leaf spot of tomato and pepper (Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatora) causes small, green-yellow spots on foliage that coalesce into large brown streaks. Spots do not have concentric rings or a halo. On tomato fruit, green fruit can become infected, and raised, brown, scab-like spots will develop.

- Bacterial speck of tomato (Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato) lesions look very similar to those of bacterial leaf spot but will eventually develop a yellow halo. Spots on fruit are dark but not raised, and the surrounding tissue is often more intensely green than unaffected areas. As with bacterial leaf spot, only green fruit is susceptible to infection.

- Angular leaf spot of cucurbits (Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans) affects all cucurbit crops, but cucumbers are most commonly affected. The pathogen is seed-borne so it often appears in the spring on cucurbit transplants. Lesions are initially small and round but become trapped by leaf veins and become angular. The centers of the lesions often crack and drop out, producing a “shot-hole” appearance. Under moist conditions, a milky white exudate containing bacterial cells may ooze out of the lesions on the lower leaf surface.

Some bacterial pathogens are capable of entering the host’s vascular system, where their proliferation blocks water-conducting vessels, causing a symptom known as vascular wilt. Plants suffering from vascular wilt will show symptoms of wilting even when soil moisture is adequate. Wilt may occur on only one side of affected hosts or may involve the entire plant.

Three common vascular diseases in vegetable crops are:

- Black rot of brassicas (Xanthomonas campestris); characteristic V-shaped lesions with brown centers and yellow margins form at the leaf margins when bacteria enter through hydathodes. Veins within lesions turn black. When bacteria enter through wounds, irregular lesions and localized vascular discoloration typically occur.

- Bacterial canker of tomato (Clavibacter michiganensis); typically causes marginal necrosis of leaves. Cankers and vascular discoloration are visible in stems. Adventitious roots are often abundant. Fruit may develop small white lesions with brown centers. Peppers are also susceptible though are not as commonly affected as tomato.

- Bacterial wilt of cucurbits (Erwinia tracheiphila); cucumbers and melons are most susceptible to this disease while symptoms in squash and pumpkin are typically milder. Cucumbers and melons develop wilting that may or may not disappear when temperatures drop in the evening. Eventually, leaves turn yellow or brown and plants collapse. Bacterial strands may be observed when the lower stem is cut and the two ends are gently pulled away from each other. Striped cucumber beetles spread the pathogen from plant to plant.

We also have had reports of tomato pith necrosis already this summer, which is a vascular bacterial disease of tomato, most commonly seen in high tunnel crops. This bacterial disease is quite different from other common bacterial diseases. Pith necrosis is caused by a weak bacterial pathogen, Pseudomonas corrugata, that infects plants that are growing too quickly. Leaves will turn yellow and stems will turn brown, although the main leader may remain green and healthy looking. Infected plants often produce lots of adventitious roots. Slicing open a stem will reveal darkly discolored vascular tissue. The disease is favored by high nitrogen fertility, cool nighttime temperatures, and high humidity. The only way to manage this disease is by avoiding favorable conditions, especially excessive nitrogen.

Management of bacterial diseases can be challenging, both in the greenhouse and in the field. They are best controlled by an integrated pest management (IPM) plan including elements such as crop sanitation, cultivar selection, and preventative application of bactericides. It is also helpful to understand a few things about bacterial biology.

Most plant pathogenic bacteria are capable of growing at a wide range of temperatures, but they tend to thrive at slightly warmer temperatures than many fungi, and each has an optimum range in which disease development is most likely to occur. For instance, Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, which causes a leaf spot on solanaceous crops, is most active at 61-75°F, while the optimum temperature range for Xanthomonas species is 77-86°F. Although disease development may slow or even cease at temperatures well outside the optimum, infections may simply remain quiescent until environmental conditions once again become conducive to disease.

While bacteria may sometimes be present in aerosols and can be carried on the wind, they are generally not as easily moved about by air currents as fungal spores are. Bacterial transmission between plants is most commonly facilitated by splashing water (especially wind-driven rain and overhead irrigation) and human activity. Insects may also carry bacteria on their bodies or in their saliva. Unlike many fungi, bacteria cannot penetrate host tissue directly, but instead must enter through small wounds or natural openings such as stomata and hydathodes. Plant pathogenic bacteria require the presence of free moisture for several hours in order to cause infection, and so prolonged periods of high humidity and leaf wetness are highly conducive to disease development. Cultural management practices aimed at lowering humidity and leaf wetness duration are therefore critical for disease prevention. In the greenhouse, these practices include heating and ventilating and increasing horizontal air flow by using fans. In the field, use drip irrigation instead of overhead, and plant in areas of full sun, adequate soil drainage, and good air circulation. Proper plant spacing and weed management should be employed in both scenarios.

Start with clean seeds and transplants. A good IPM program involves starting with clean seeds and transplants. Like some fungal diseases, bacterial diseases can also be seed-borne. Hot water treatment can significantly reduce the number of bacterial cells present in seed. The UMass Extension Vegetable Program offers a hot water seed treatment service; click here for more information. If pots or stakes must be re-used, they should be sanitized. Do not save seeds from infected plants. Grow resistant varieties when available. Some bacterial pathogens (e.g. Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, which causes leaf spot of peppers) are comprised of several races, so keep in mind that resistant cultivars may not be resistant to all races. Current information on disease resistant vegetable cultivars may be found at vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/Tables/TableList.htm.

Field sanitation. Most plant pathogenic bacteria do not survive more than a month or two on their own in the soil; however, they can survive for much longer inside of infected plant debris in the soil and may also persist in perennial weeds. Sanitation is therefore another important cultural practice for disease prevention and management. Remove infected plants and plant debris from the greenhouse or field. It is also advisable to remove healthy looking plants adjacent to symptomatic ones. In the field, plow deeply at the end of the season to bury remaining plant debris and speed its breakdown. In no-till systems, remove crop debris as thoroughly as possible and dispose of it off-site. Rotate away from host crops for at least two years. In addition to decreasing relative humidity, good weed management also removes alternative host plants.

Chemical control. Some fungicides containing copper, copper plus mancozeb, and phosphorus acids also have bactericidal activity and are labeled for use on vegetables. Organic products based on botanical oils, Bacillus species, and other ingredients may also be helpful. Trade name of products with those active ingredients can be found in Table 26 of the New England Vegetable Management Guide. Keep in mind, however, that the efficacy of these products is limited and there is no substitute for good crop management practices.

Tips for maximizing spray efficacy include the following:

- Obtain an accurate diagnosis. With the exception of those mentioned above, most fungicides have no effect on bacteria. Knowing that a disease is caused by a bacterium and not a fungus enables the grower to select an effective product to apply, potentially saving time, money, and unnecessary applications of pesticides.

- Be aware that none of these products can cure a plant that is already infected, but they can help prevent healthy plants from becoming infected; therefore, they are best used as protectants.

- Thorough coverage is imperative.

- Remove symptomatic plants and plant debris from the greenhouse or field as thoroughly as possible before spraying.

- Don’t apply bactericides when plants are wet or use an air blast sprayer. The force of the air blast sprayer can spread drops of moisture containing bacteria among plants and at the same time cause small wounds through which infection can occur.

- Do not rely on copper alone for bacterial disease management. Copper-resistant strains of some plant pathogenic bacteria have been identified.

- Experimental evidence suggests that greater efficacy may be achieved when a plant defense activator like acibenzolar-s-methyl (e.g., Actigard) or extract of Reynoutria (e.g., Regalia) is included in the spray program.

--Written by Angela Madeiras, UMass Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab

Garlic Harvest, Curing, & Storage

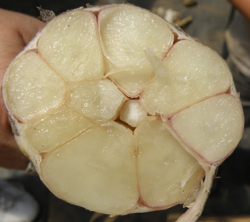

Garlic harvest is fast approaching and has happened already on some farms. This is a big task that usually occurs around mid- to late July. As you start to prepare for garlic harvest, here are some tips from Crystal Stewart-Courtens of Cornell Cooperative Extension, on determining ideal harvest timing: heads should be left in the ground as long as possible to attain maximum bulb size (which doubles in the last stage of growth), but not so long that the cloves begin to separate, as overripe bulbs sell and store poorly. Harvest when leaves begin to turn yellow, but when about 60% are still green—one rule of thumb is to harvest when there are a minimum of three leaves left that have not begun to brown at the tips. Check bulbs by cutting through the head sideways to see if the cloves fill the wrappers – if they are loose within the wrappers, the garlic has a little ways to grow. A little of the outermost wrapper may have started to discolor at this point. Harvest before the cloves start to separate from each other within the bulb, which can happen relatively quickly, especially in a wet year. It is better to harvest too early than too late. Find more harvest and storage tips from Crystal in Veg Notes from a few weeks ago!

Garlic harvest is fast approaching and has happened already on some farms. This is a big task that usually occurs around mid- to late July. As you start to prepare for garlic harvest, here are some tips from Crystal Stewart-Courtens of Cornell Cooperative Extension, on determining ideal harvest timing: heads should be left in the ground as long as possible to attain maximum bulb size (which doubles in the last stage of growth), but not so long that the cloves begin to separate, as overripe bulbs sell and store poorly. Harvest when leaves begin to turn yellow, but when about 60% are still green—one rule of thumb is to harvest when there are a minimum of three leaves left that have not begun to brown at the tips. Check bulbs by cutting through the head sideways to see if the cloves fill the wrappers – if they are loose within the wrappers, the garlic has a little ways to grow. A little of the outermost wrapper may have started to discolor at this point. Harvest before the cloves start to separate from each other within the bulb, which can happen relatively quickly, especially in a wet year. It is better to harvest too early than too late. Find more harvest and storage tips from Crystal in Veg Notes from a few weeks ago!

Use hand tools to loosen soil under the bulbs or a mechanical harvester to undercut the bed. Pulling bulbs out when they are tight in the ground can open wounds at the stem-bulb junction and allow for fungal infections. Fresh bulbs bruise easily and these wounds can also encourage infection. Don’t knock off dirt by banging bulbs against each other, boots, shovels, or buckets— shake or rub gently, and leave the rest to dry out during curing.

If short on curing space, tops can be cut in the field, with a sickle bar mower or by hand, leaving stems as short as 1.5” or as high as 6”. In many cases, topping vs. not is dictated by curing scenarios—leaving tops on can facilitate hanging bulbs to cure, whereas topping plants is more conducive to curing in bulb crates or mesh bags. Recent Cornell trials have indicated that disease incidence does not increase when trimming garlic down at this stage.

Curing is important for successful bulb storage and finding the ideal conditions for curing can be a challenge. Curing in the field runs the risk of sunscald, while curing in poorly ventilated barns can result in yield loss from disease. Good airflow around the bulbs is critical. Avoid high temperatures (above 90°F) and bright sunlight. Stewart-Courtens notes that garlic will dry well even at 110°F but a physiological disorder called waxy breakdown starts to occur at about 120°F, so be sure to monitor temperatures in the drying area. Rapid curing can be achieved by placing trimmed bulbs roots-up on 1” wire mesh in a hoophouse or high tunnel covered with shade cloth, and with the sides and ends open. A well-ventilated barn will also work, but be sure that bulbs are hung with adequate air circulation or on open racks up off the floor. Curing takes 10 to 14 days and is complete when the outer skins are dry and crispy, the neck is constricted, and the center of the cut stem is hard.

Curing is important for successful bulb storage and finding the ideal conditions for curing can be a challenge. Curing in the field runs the risk of sunscald, while curing in poorly ventilated barns can result in yield loss from disease. Good airflow around the bulbs is critical. Avoid high temperatures (above 90°F) and bright sunlight. Stewart-Courtens notes that garlic will dry well even at 110°F but a physiological disorder called waxy breakdown starts to occur at about 120°F, so be sure to monitor temperatures in the drying area. Rapid curing can be achieved by placing trimmed bulbs roots-up on 1” wire mesh in a hoophouse or high tunnel covered with shade cloth, and with the sides and ends open. A well-ventilated barn will also work, but be sure that bulbs are hung with adequate air circulation or on open racks up off the floor. Curing takes 10 to 14 days and is complete when the outer skins are dry and crispy, the neck is constricted, and the center of the cut stem is hard.

Storing Bulbs. After curing, garlic can be kept in good condition for 1 to 2 months at ambient temperatures of 68 to 86°F under low relative humidity (< 75%). However, under these warm conditions, bulbs will eventually become soft, spongy and shriveled due to water loss. For long-term storage, garlic is best maintained at temperatures of 30 to 32°F with low relative humidity (60 to 70%). Good airflow throughout storage containers is necessary to prevent any moisture accumulation. Under these conditions, well-cured garlic can be stored for 6 to 7 months. Storage at higher temperatures (60°F) may be adequate for the short term, but it is important to select a place with low relative humidity and good air flow. As with onions, relative humidity needs to be lower than for most vegetables because high humidity causes root and mold growth; on the other hand, if it is too dry, the bulbs will dry out.

Storing Seed. Garlic bulbs that are to be used as seed for fall planting of next years’ crop should be stored at 50°F and at relative humidity of 65 to 70%. Garlic cloves break dormancy most rapidly between 40 to 50°F, hence prolonged storage at this temperature range should be avoided. Storage of planting stock at temperatures below 40°F results in rough bulbs, side-shoot sprouting (witch’s brooms) and early maturity, while storage above 65°F results in delayed sprouting and late maturity.

| Storage scenario | Length of Storage | Temperature | Relative Humidity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term | 1-2 months | 68-86°F | <75% |

| Long-term | 6-7 months | 30-32°F | 60-70% |

| For seed | 50°F | 65-70% |

Garlic cloves used for seed should be of the highest quality, with no disease infections, as these can be spread to new fields and to the next year’s crop. See our Culling Garlic: Don’t Store or Plant Infected Bulbs article for what diseases and pests to look out for when preparing seed garlic. One of the most important clove-borne pests of garlic is garlic bloat nematode—keep an eye out for symptoms of this devastating pest and submit samples to the UMass Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab to make a positive identification; for submission instructions and contact info visit https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory.

Over 2019 and 2020, Christy Hoepting of Cornell Cooperative Extension, conducted trials to evaluate various garlic curing and storage conditions. A planting of German hardneck garlic was divided up between 13 and 24 storage regimes in 2019 and 2020, respectively, and bulb characteristics including % shrink, bulb density, bulb firmness, wrapper tightness, bulb color, and Fusarium and black mold incidence were evaluated. Here are some take-home messages from the trials:

- The best-performing treatment was curing in a greenhouse with open sides, no fans, with garlic in mesh bags in a single layer on wooden pallets. After curing, the garlic was stored in a steel barn, where temperatures never dropped below 50°F and relative humidity ranged from 50-80%.

- Warm and humid storage conditions resulted in high incidence of Fusarium bulb rot, as would be expected.

- Cold storage reduced the incidence of Eriophyid mites, as lower temperatures inhibit their reproduction. E. mite populations will grow at room temperature.

- No consistent trends were observed in regards to topping vs. not topping. Neither practice led to higher rates of disease incidence or consistent differences in bulb quality. However, it does take longer to cure garlic with tops on (see Table 1).

- Washing or rainfall during curing reduced bulb quality and increased disease.

- Curing garlic in 1-ton boxes with heated forced air reduced bulb quality.

| Curing Condition | No. of Days to Complete Curing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Topping Conditions of Garlic During Curing | |||

| Temperature | Relative Humidity | Topped to 2-3" necks | Topped to 6-7" necks |

| 80°F | 90% | 19 days | 33 days |

| 80°F | 70% | 11 days | 19 days |

| 105°F | 90% | 7 days | 9 days |

| 105°F | 70% | 6 days | 7 days |

A useful summary from Hoepting’s write-up:

"No matter the post-harvest practices used by our growers, the garlic came back fairly high quality. If you are happy with the quality of your garlic, do not change a thing. If your garlic has softer bulbs and looser wrapper leaves than you would like, consider adjusting your curing or storage conditions. Perhaps, it is being kept in the curing phase for too long and is being overdried. Maybe, you can cure it slower with natural ventilation instead of with fans, or top the bulbs to leave a longer neck (e.g. 6”). If you have issues with eryophyid mites showing up after storage, consider storing your garlic under cooler conditions. In very general terms, high humidity (>85%) for prolonged periods of time, no matter the temperature, can exacerbate diseases."

--UMass Extension Vegetable Program. Cornell Cooperative Extension garlic storage trials originally reported in Cornell Veg Edge Volume 18 Issue 14, on July 13, 2022.

News

New MDAR Service: Farm Transfer Plan Assistance or Farm-Pass

MDAR’s new Farm-Pass Program will provide direct assistance to help Massachusetts farm owners pass their farm on to the next generation. This service is targeted to owners who have already identified a successor – either within the family or not – who is interested in transitioning to own and manage a commercial farm business on the farm property in the near future. This is a no-cost opportunity for farm owners, family members, and the identified successor to work one-on-one with an experienced, dedicated planner to create a customized farm transfer plan. Participants will meet regularly to set goals for retirement and the future farm business, and create tangible next steps to transfer assets and management.

MDAR's Farm Transfer Plan assistance program will match participants with a professional planner with experience working with farms on business management, financials, and farm transfer to meet regularly over the course of approximately one year. The planners will NOT provide legal or tax advice but WILL help you develop a written action plan that identifies concrete next steps to work on with your attorney and/or CPA/tax advisor to make the transfer happen.

Three rounds of this program are anticipated under this RFR. Applications will be accepted on a rolling basis, but must be received by the following dates in order to be considered for each round’s start date as follows:

- To start by August 30, 2024, applications must be received by July 15, 2024.

- To start by March 1, 2025, applications must be received by January 15, 2025

- To start by June 1, 2025, applications must be received by April 15, 2025

CLICK HERE to apply. The PDF titled “AGR-FTPA-FY25-26” is the Request for Response with information and the application form.

Questions? Contact Melissa Adams, 857-276-2377, Melissa.L.Adams@mass.gov or Laura Barley, 857-507-5548, Laura.Barley@mass.gov.

39th Massachusetts Tomato Contest to be Held on August 20

The 39th Massachusetts Tomato Contest will be held at the Boston Public Market on Tuesday, August 20. Tomatoes will be judged by a panel of experts on flavor, firmness/slicing quality, exterior color and shape. Always a lively and fun event, the day is designed to increase awareness of locally grown produce.

Open to commercial farmers in Massachusetts, growers can bring tomatoes to the market between 8:45 am and 10:45 am on August 20 or drop their entries off with a registration form to one of the regional drop-off locations on Monday, August 19. Drop off locations include sites in South Deerfield, Southboro, North Easton and West Newbury. These tomatoes will be brought to Boston on Tuesday.

For complete details, including drop off locations, contest criteria, and a registration form, click here. Be sure to include the registration form with all entries.

The Massachusetts Tomato Contest is sponsored by MDAR and New England Vegetable and Berry Growers Association, in cooperation with the Boston Public Market. Please consider participating to showcase one of the season’s most anticipated crops!

Questions? Contact David Webber, David.Webber@mass.gov.

Events

Field Walk at Astarte Farm - Hadley, MA

When: Tuesday, July 9, 2024, 4-6pm followed by light dinner

Where: Astarte Farm, 123 West St., Hadley, MA 01035

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join Astarte Farm, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program and NOFA/Mass for a twilight meeting!

- Ellen and Dan from Astarte Farm will lead a tour of the farm, highlighting pollinator habitat that they've installed. The habitat was installed with funding from NRCS.

- Hannah Whitehead, UMass Extension Educator, will talk about the benefits of pollinator habitat for organic farmers.

- Sarah Berquist, UMass Lecturer and cut flower farmer, will discuss the flowers that she grows at Astarte.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is supported by and MDAR Specialty Crop Grant and the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Field Walk at Morning Glory Farm - Edgartown MA

When: Wednesday, July 17, 2024, 6-8pm

Where: Morning Glory Farm, Edgartown, MA

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension specialists Sue Scheufele and Maria Gannett for a field walk at Morning Glory Farm. We will identify current pest and weed issues in vegetable crops and discuss their management. There will be lots of time for Q&A, discussion, and dinner and refreshments will be provided.

2 pesticide recertification credits are available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by NOFA/Mass and Martha’s Vineyard Ag Society with support from the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Water & Climate Change Twilight Meeting at Bardwell Farm – Hatfield, MA

When: Friday, August 2, 2024, 5-7pm, with dinner and discussion to follow

Where: Bardwell Farm, 49 Main St., Hatfield, MA 01038

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension and CISA for a climate-themed twilight meeting at Bardwell Farm in Hatfield, MA!

- Lisa McKeag will share findings from her recent water quality survey of farms around MA and discuss potential risks and impacts of weather and climate change and rising year-round temperatures on agricultural water quality.

- Harrison Bardwell will show off his new automated irrigation system, and discuss irrigation practices and funded projects around the farm.

- Sue Scheufele will discuss increasing pest risks caused by a hotter climate on vegetable pests including an on-farm trial for managing Phytophthora blight in peppers hosted by Bardwell Farm.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Save the Date! UMass Research Farm Field Day

When: August 13, 2024, time TBD

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA

Registration: Coming soon!

Come learn about all the research being done by students and faculty across CNS and by UMass Extension on a tour of the farm. Topics include pollinator habitat, bee health and disease ecology, novel cover cropping strategies, intercropping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, genetic basis of flowering traits in agriculture, and vegetable variety trials including heat-resistant lettuce varieties for summer production.

Field Walk at Siena Farms - Sudbury, MA

When: Wednesday, August 21, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Siena Farms, 113 Haynes Rd, Sudbury, MA 01776

Registration: Free! Please register in advance, for food ordering purposes. Click here to register.

Join us for a field walk at Siena Farms! Someone from the farm will discuss their sunflower production, and the UMass Extension Vegetable Program will lead a pest walk. Light dinner and refreshments will be served at the end, with plenty of time to talk with fellow growers!

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is funded by a grant from the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture.

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference - Registration Now Open!

When: Tuesday - Thursday, December 17-19, 2024, 8am-6pm daily

Where: Doubletree Hotel, 700 Elm St., Manchester, NH 03101

Registration: Before November 30, $115/person, or $85 for additional attendees if registering as a group. Students $50. Registration capped at 1,400. Click here to register.

The NEVF Conference includes more than 25 educational sessions over three days, covering major vegetable, berry and tree fruit crops as well as various special topics. A Farmer-to-Farmer meeting after each morning and afternoon session will bring speakers and farmers together for informal, in-depth discussions on certain issues. The extensive trade show has over 120 exhibitors.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.