By Michele Meder, Genevieve Higgins, and Susan B. Scheufele

Background and Objectives

Cabbage aphid populations have been increasing in recent years and are now a major concern across New England. Brussels sprouts are especially susceptible, since aphids get into buds and are hard to reach with pesticide sprays. Therefore, alternative methods for controlling aphids are necessary. In other systems, interplanting with insectary plants (flowers that provide pollen and nectar and can serve as food and habitat for beneficial insects) is standard practice. One example of this is lettuce production in CA, where alyssum is planted every so often in the bed to support insects which are predators and parasitoids of aphid pests. Cabbage aphids are a little different than aphid pests of lettuce—they are larger and contain sulfur compounds that are not appealing to some predators—but nevertheless there is a large body of literature supporting the idea that predators (especially syrphid fly larvae) and parasitic wasps (especially the native braconid wasp, Diaeretiella rapae) can impact cabbage aphid populations in the field. The purpose of this study was to compare several species of insectary flowers to see if any are more attractive to syrphids and parasitic wasps, and to identify which species of syrphids and wasps are present in New England. Similar studies were conducted in NH and CT in 2018.

Methods

Brussels sprouts were planted around the experiment in order to provide cabbage aphid hosts to help attract predators and parasitoids. Each flower was grown in a 15-sq. ft. plot and replicated four times. The insectary flowers tested were:

- Alyssum 32 plants/plot

- Buckwheat direct seeded at 6” spacing

- Phacelia direct seeded at 12” spacing

- Calendula 32 plants/plot

- Dill 36 plants/plot

- Cilantro 36 plants/plot

- Ammi 32 plants/plot

Plants were direct-seeded or transplanted on July 13th, except Ammi majus which was planted on July 6th, and cilantro and dill which were planted on July 20th. The Phacelia never germinated so we have no data on that plant this year; in past years it was very attractive to a diversity of insects. To assess the relative attractiveness of each species of flower, we observed plots in 2-minute increments and recorded the number of syrphids, small wasps, and other insects landing on flowers within a 1 square foot area. We then sampled from each plot with a 15 inch muslin sweep net and later characterized the number and types of insects collected. We also recorded information about the weather, time of day, and flowering activity at the time of sampling. Over the winter, we identified wasps and syrphids as best as possible.

Results & Discussion

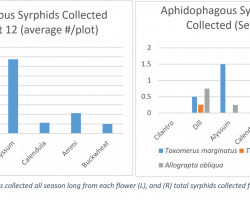

The first flowers to open were Ammi, which were started earlier in the greenhouse, in late-July. Calendula, buckwheat, and alyssum began flowering on August 3rd and dill and cilantro began flowering on August 23rd and September 4th, respectively. When we look at the total number of syrphids from aphid-eating (aphidophagous) groups collected in sweep nets, the alyssum had by far the most, followed by dill and then cilantro and Ammi (Figure 2-L). These flowers all have small petals and very open habits or umbels. In order to compare all the flowers side-by-side, we must look only at dates on which all flower species were open, which is unfortunately only two dates in September (Figure 2-R). On these dates, again we see far more aphidophagus syrphids on alyssum, and just a few individuals on dill, Ammi, and buckwheat. The greatest diversity of syrphids was found on dill.

Of the aphidophagus syrphids collected, Toxomerus marginatus was by far the most common; others we collected included Taxomerus germinatus,

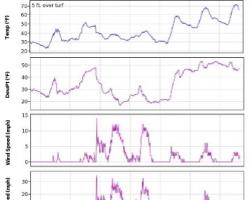

Melanostoma mellinum, Allograpta obliqua, and a Sphaerophoria species. The number of T. marginatus collected increased in early-September and then plummeted in late-August, as weather became gray, windy, and rainy. When the sun came out again in October, we started collecting lots of T. marginatus again. This species seems to be present during most of the fall brassica growing period and would be a useful species to continue to try to attract into our brassica fields.

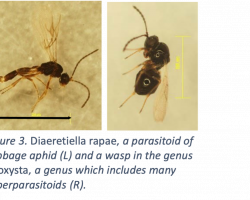

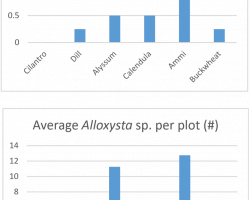

Our collection of small and potentially parasitic wasps is quite large and diverse. These specimens have turned out to be much more difficult to identify to species or even to genus than the syrphids, and we are still working on identifying them. At least several commonly collected wasps are braconids or ichneuomonids, which are both groups that include parasitoids of vegetable pests. Other commonly collected wasps are from groups that parasitize the parasitoids (hyperparasitoids), making things more complicated. We have positively identified D. rapae, the native parasitoid of cabbage aphid, in our sweet net collections, and we have also observed it hatching out of mummified aphids collected from the field (Figure 4). We collected the most D. rapae from Ammi, perhaps indicating a preference for that flower relative to other flower species tested (Figure 5). We believe that another commonly collected wasp is a member of the genus Alloxysta, which includes known hyperparasitoids of beneficial braconid and apheliniid wasps (Figure 4). This wasp was collected from all of the flowers, but was collected in greatest numbers from Ammi and alyssum (Figure 5).

Conclusions

This long-term regional survey for predators and parasitoids of cabbage aphids has gotten off to a great start, with all three cooperating institutions developing shared protocols for planting, observing, and collecting beneficial insects in brassica fields. So far, we have identified many aphidophagous syrphids and parasitic wasps collected from insectary flowers, and have determined that many are common across states. One challenge we encountered was that we collected such a large number and diversity of wasps that we had difficulty identifying all of them. In the future, we may consider collecting aphid mummies from farms across New England and characterizing only wasps that hatch out of these mummies, in order to narrow down our survey to include only these species of wasp. Other future directions may include: evaluating different flower species; investigating when different syrphids or wasps are active throughout the season; looking at other factors that seem to play a role in cabbage aphid outbreaks, including entomopathenogenic fungi, heavy rain, and other cultural practices.