A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content.

To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Featured Fungus: Downy Mildew of Coleus

Downy mildew of coleus is caused by the oomycete Peronospora choii. Symptoms include yellowing and/or browning of leaves, distortion, and leaf drop. Under humid conditions, sporangia (spores) are produced on a fuzzy gray to purplish growth on leaf undersides. Seedlings may be stunted or killed.

Downy mildew of coleus is caused by the oomycete Peronospora choii. Symptoms include yellowing and/or browning of leaves, distortion, and leaf drop. Under humid conditions, sporangia (spores) are produced on a fuzzy gray to purplish growth on leaf undersides. Seedlings may be stunted or killed.

This disease was originally believed to be Peronospora lamii, which causes downy mildew on mint. Genetic studies, however, have found that it is distinctly different from P. lamii and from P. belbahrii, which causes downy mildew of basil. Peronospora choii does not infect basil or mint, nor do the species found on these plants infect coleus. Agastache and perilla are also believed to be susceptible to P. choii.

Cool (59-68°F), humid conditions favor infection and development of sporangia. Sporangia are carried by air currents and splashing water to other plants, where they germinate on wet leaf surfaces and infect host tissue. The cycle continues as long as environmental conditions are conducive. In warmer (>77° F), less humid environments, symptoms may not develop on infected plants, appearing only when the temperature decreases.

Long term survival strategies for Peronospora choii have yet to be elucidated. Production of oospores, the thick-walled survival structures that allow some downy mildews to persist in soil, have not been reported in coleus downy mildew. It is also uncertain if the pathogen is seed-borne. When buying coleus, be sure to inspect plants carefully and buy plants that appear healthy.

Angela Madeiras, UMass Extension Plant Pathologist

Trouble Maker of the Month

Spotted Lanternfly Updates & Where to Report Sightings in Massachusetts

By the time this issue of Hort Notes is published, the invasive spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) will have hatched from its overwintering egg masses in locations where it has become established* in Massachusetts.

It remains important to look for and report any life stages of this insect that are found in Massachusetts. This includes the nymphs (immatures) as well as the adults and the egg masses the females will lay at the end of summer into fall. Any signs of this insect should be immediately reported to the MA Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR), at https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx .

*At the time of this publication, spotted lanternfly populations have been detected in Worcester County, MA (Fitchburg, Worcester, and Shrewsbury) and Hampden County, MA (Springfield).

Should I Be Treating for Spotted Lanternfly in Massachusetts?

That depends on a few factors. Is the property located in parts of Worcester and Hampden Counties where the spotted lanternfly has been established? Has MDAR been notified of the infestation in this exact location using the link above? Does the property have a population of the insect currently present? If so, is it threatening the health of high-value host plants (such as grapes/vineyards, but damage has also been observed by the scientific community on maple or black walnut)? If you’ve answered yes to all of these questions, management may be warranted.

This Spotted Lanternfly Management Fact Sheet provides helpful information and suggestions for next steps for land managers in Massachusetts.

How is the MA Department Agricultural Resources Currently Responding to SLF?

The MA Department Agricultural Resources (MDAR) continues to ask that all professionals and residents of Massachusetts report sightings of the spotted lanternfly in the state. MDAR officials have been busy! They have been scraping and destroying egg masses over the winter at high priority sites in Massachusetts that had the largest populations of adults seen in 2022. State and federal officials continue to work together to trap and monitor spotted lanternflies in high-risk locations (ex. along travel corridors) in Massachusetts. MDAR continues to work with nurseries if accidentally infested shipments arrive from other states with active spotted lanternfly populations. This includes asking nursery owners and operators to be trained on how to identify spotted lanternfly, display educational materials for their staff members and the public, and make use of current best management practices in the event treatment or mitigation is necessary. MDAR is currently assessing existing infestations in Worcester and Hampden Counties to determine whether insecticide treatments at high priority locations may help reduce populations of this pest.

Did you miss the quarterly spotted lanternfly update from MDAR? Not to worry! Watch the most recent update from May 17th.

Also, check out these hot off the press resources from MDAR:

Spotted Lanternfly Look-alikes in MA

Spotted Lanternfly Egg Mass Look-alikes

Tawny Simisky, UMass Extension Entomologist

Q&A

Q. Recently, in videos on social media, I’ve been intrigued to see clover used in place of turfgrass for lawns. Is this something I should consider for my New England lawn?

A. A key distinction here is whether the interest is in a lawn composed entirely of clover, or of some clover mixed with traditional turfgrasses.

At the outset, there is seemingly a lot to like about clover as a lawn alternative. Clover is vigorous, low maintenance, heat and drought tolerant (generally… more on this below), attractive to pollinators, and perhaps most notably, fixes its own nitrogen supply from the atmosphere on account of a symbiotic relationship with special bacteria.

Much of the attention given to lawns centers on appearance, so much that folks frequently overlook the critically important functional “work” that turf does for us on a given site… services that we often take for granted. These include helping to protect the soil from disturbance and compaction (see next question below), providing a durable and uniform surface for recreation, preventing erosion, reducing dust and mud, and mitigating stormwater runoff, among many other beneficial services.

Compared with common turfgrasses, clover alone is simply not as effective at a number of these functional services. Notably, and despite some claims, commonly available species and varieties of clover do not have good wear and traffic tolerance (a principal consideration for the average lawn subject to moderate to high use), at least relative to well-adapted turfgrasses. When the surface is damaged by wear, clover is also not as adept at healing and recovery.

The long dormant season in New England also works against a wholly clover lawn. Succulent clover top growth dies back completely with the onset of cold weather, leaving little to no ground cover, and therefore vulnerable soil and a less functional site overall. This is another departure from what we comonly see with turfgrasses, which is that much of the dead shoot tissue persists and continues to perform those important services throughout the winter months.

Even in-season, under favorable conditions when plants are growing well, clover does not occupy available space as effectively and uniformly as turfgrasses. Thus, weed encroachment potential is increased. If there is a desire to manage those weeds, it can be very challenging to do so in a selective manner with applications of readily available management materials without also harming the clover.

All of that said, clover can be a viable and beneficial component of predominantly turfgrass lawns for those who can appreciate the aesthetic. In fact, this was an approach that was much more mainstream and common in decades past than it is today.

Nitrogen dynamics are central to maintaining turfgrass/clover mixtures. Some studies have shown that clover can produce up to 1 lb of N per 1000 square feet, depending on coverage and persistence, that directly benefits the turf community as a whole and reduces the need for applied fertilizer. Maintaining the optimum balance, however, can be tricky, as any applied N can make the grass more competitive which in turn can crowd out the clover. Where N levels are lower, the clover is often more prevalent. In all but the lowest maintenance lawns, the grass often dominates and the clover percentage tends to decline over time. Along with managing nitrogen levels, some folks also opt to overseed periodically to help maintain desired clover percentages in the stand.

When asked about planting clover as a component of turfgrass lawns, I most often point individuals in the direction of the so-called “microclover” varieties (such as ‘Pirouette’ and ‘Pipolina’), as they are readily available. These can be pricey, however, especially compared to the more standard “Dutch” white clover, which is typically much cheaper but unfortunately not a better substitute for most turf settings. The “microclover” varieties tend to grow more slowly and flower less prolifically than common white clover, but are reportedly less heat and drought tolerant relative to common varieties.

UMass has done some trials with “microclover” mixes. Observationally in these trials, the clover was vigorous but not especially “micro”… it often appeared similar in stature to standard white clover. Anecdotally, I have observed and heard that closer mowing can help maintain the smaller stature, but closer mowing runs counter to what is normally advised for most lawns, especially lower maintenance lawns in which the incorporation of clover can be most appropriate and advantageous.

Q. I hear the term soil compaction a lot with regard to plant care and soil health. What exactly is soil compaction and why is it detrimental to plants?

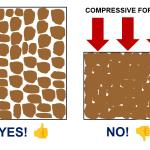

A. The solid fraction of soil has two principal ingredients: mineral fragments and organic material. What is important and valuable about soil is not only what is there, but also what isn’t there… in terms of the empty voids, the pore spaces.

These pore spaces are:

- how water infiltrates, and is held within, and drains from the soil.

- how beneficial gases (like oxygen) reach plant roots, and how detrimental gases escape.

- where plant roots grow.

Although this is a textbook example and almost never realistic, the perfect soil for the growth of most plants would be somewhere along the lines of 50% pore space… so essentially half empty space. The other 50%, the solid fraction, would be approximately 45% mineral material and about 5% organic matter.

W hat compaction involves are compressive forces, such as foot or vehicle traffic, that essentially collapse and crush this precious soil pore space, thereby making it smaller. “Heavier” soils with higher clay content and/or higher organic matter content compress much more readily and are therefore more prone to compaction. “Lighter”, sandier soils are more compaction resistant. Soil compacts more easily when it is wet (water lubricates soil particles and causes them to move and shift more readily), and less so when it is dry.

hat compaction involves are compressive forces, such as foot or vehicle traffic, that essentially collapse and crush this precious soil pore space, thereby making it smaller. “Heavier” soils with higher clay content and/or higher organic matter content compress much more readily and are therefore more prone to compaction. “Lighter”, sandier soils are more compaction resistant. Soil compacts more easily when it is wet (water lubricates soil particles and causes them to move and shift more readily), and less so when it is dry.

Compaction is measured in terms of bulk density… the amount of solid material per unit volume. A higher bulk density means more solid material per unit volume, which translates to less pore space and higher compaction severity. These measurements can be made with the right field equipment or with the help of a soil testing lab. Often, compaction can be diagnosed imprecisely, using cues such as pooling of water due to poor drainage, thinning of groundcovers such as turfgrasses, or prevalence of compaction tolerant weeds such as path rush (Juncus tenuis).

Greater compaction means fewer resources for roots (the foundation of the plant system), which are doubly compromised by having less physical real estate in which to grow. This means greater overall stress, more plant energy and resources required to combat these challenges, reduced plant performance, and higher maintenance demands. A big takeaway for compaction is that it is a chronic condition, meaning that it has the potential to increase gradually over time in response to repeated compression events. Once soil is significantly compacted, it is very difficult to remedy without major and disruptive intervention.

The best compaction solution is prevention. Soil is most vulnerable when it is “open”, or bare, so prevention should start immediately at the time of construction or plant establishment. This might involve steps like minimizing heavy equipment use, removing and stockpiling topsoil during sitework, conducting necessary screening or mixing activities off-site, and not working the soil when it is wet. In established landscapes and gardens, management includes minimizing traffic stress (especially when soil is wet, such as in early spring); eliminating exposed soil by way of grasses, groundcovers, or mulches; varying patterns when traffic can’t be avoided (such as varying mowing patterns on lawns) and/or restricting traffic to dedicated paths; and use of proper cultivation practices when and where appropriate.

Jason Lanier, UMass Extension Turf Specialist

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

June is the month to . . . .

-

Prune spring flowering shrubs that have finished blooming. Shrubs such forsythia, viburnum, honeysuckle, lilac, azalea and rhododendrons are generally pruned soon after flowering. Spring flowering shrubs form their flower buds in mid- to late summer and flower the following spring on one-year old shoots. Pruning them after they have bloomed encourages formation of new flower buds for next season. Pruning them in early spring, late summer, or fall removes the flower buds and reduces the number of flowers in the spring. If full display of flowers is not important to you, then pruning them in early spring is not a problem.

-

Plant tender annuals and warm season vegetables. Tender annuals, herbs and warm season vegetables such as tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers can be planted in early June after the danger of frost is past. Before planting, make sure you prepare the soil well and incorporate compost or manure by tilling it in 6″ to 8″ deep. Compost or manure improves the soil structure and adds some nutrients to the soil. However, they don’t supply adequate nutrients to support healthy vegetable crops or garden plants. In addition, apply an organic or slow release fertilizer to ensure your vegetable crops and flowers have nutrients they need for optimal growth.

-

Add new mulch to beds as needed. If beds already have mulch from last year, a top dressing of a thin 1-inch layer with new mulch is adequate. For new beds, spread a 2-3 inch layer of mulch, being careful not to spread mulch over the crowns of perennial plants or pile it against the stems of shrubs or trees. Organic mulches such as ground bark, ground wood chips, or shredded leaves can provide benefits such as weed suppression, conserve soil moisture, reduce soil temperature, add organic matter, and enhance appearance.

-

Thin cool season vegetable crops planted in May. Cool season crops such as spinach, beets, radishes, carrots and lettuce are sowed thickly in rows and thinned later to the desired spacing to allow them to develop properly. Root crops such as carrots, beets, and radishes should be thinned to a 2-inch spacing to allow the roots to develop properly. These can be thinned as soon as they reach small edible size.

-

Weed the garden. Weeds compete with plants for nutrients and moisture. Do not ignore weeds until they get out of control but control them early. Controlling weeds early will be more effective and will take less time and effort. Weeds can be controlled by cultural methods such as cultivating, hoeing, and mulching or by using herbicides. Generally, cultural weed control provides good results, but in cases where a garden is overgrown with weeds, an herbicide may be more effective.

-

Thin excess fruits from fruit trees. After natural fruit-drop of apples, pears and peaches, thin excess fruits in order to produce larger fruits. When you remove some of the fruits on a branch, the remaining fruit develops to adequate size and quality. Thinning also reduces total fruit load on the branches and prevents breakage. If thinning is done early, it also helps increase the plants' ability to form more flower buds for next year.

-

Construct trellises for vining vegetables and ornamental plants. If you are growing vining vegetables such as cucumbers, pole beans, indeterminate (tall) tomatoes, and vining ornamental plants such as clematis, wisteria, and trumpet vine, construct trellises that are sturdy, durable and match your style. Train young vines to get the desired growth pattern.

-

Move houseplants outdoors for cleaning and repotting as needed. Houseplants that are too big for their pots can benefit from repotting, which can be an invigorating process for the plants. When repotting plants, select a pot that is 1 or 2 inches larger than the original pot. Trim off any rotted roots and pull apart circling roots before repotting. Houseplants growing in lower light levels in the house should be first placed in partial shade outdoors to prevent sunburn on leaves.

-

Start regular scouting for insect pests and diseases. Starting to scout early for insect pests and diseases and taking appropriate control measures will help limit the damage to plants. Scouting involves observing plants regularly, looking at all parts of the plant including tops and undersides of leaves and at the soil line. You may need a hand lens to see some insects and signs of disease. Before taking control measures, determine whether the damage is due to an insect pest, disease, or cultural practice.

Geoffrey Njue, UMass Extension Sustainable Landscapes Specialist

Shrub Multi-Season Standouts

There are plants in the landscape that have their shining moment for a couple of weeks and then fade into the background, the one hit wonders of the plant world (I’m looking at you Linnaea amabilis [fomerly Kolkwitzia]). While in their prime, they may be so showy that they warrant a spot in the landscape even if they lack multiple seasons of appeal. However, other plants show up for us throughout the year - floriferous in the spring, quality summer foliage or fabulous fall color, interesting bark in the winter. These multi-season standouts provide interest season after season. With limited space in many landscapes, plants with multiple seasons of appeal are ideal for creating visual interest throughout the year.

Large shrubs (or large shrubs trained to be small trees) can serve as the focal plant when other ornamental trees are too large. Amelanchier canadensis, commonly known as serviceberry is a great example. Serviceberry is a native, large shrub to small tree growing 15-30’ tall and 15-20’ wide. Trees are covered in small, white, five-petaled flowers in spring before leaf emergence. Unfortunately, flowers are showy but short lived, only lasting 1-2 weeks. Flowers give way to small green berries which turn red before maturing to black in fall. Leaves are medium to dark green in summer, turning a mix of orange and red in the fall. The fruit is edible and is attractive to birds. Plants are best grown in average, well-drained soil in full sun to part shade. Serviceberry is best used in woodland gardens, where it’s more natural form is best appreciated, but it can also be utilized in more formal landscapes as a small tree. Amelanchier spp. are also an early source of pollen and nectar for many species of bees and butterflies. There are multiple Amelanchier species appropriate for New England landscapes, all with similar ornamental features to A. canadensis.

Next we have a sampling of shrubs with lovely spring flowers and beautiful fall fruit and foliage. Aronia arbutifolia, red chokeberry, is native to the eastern US. The cultivar ‘Brilliantissima’ is most commonly found in the nursery trade. It is more compact than the species, growing 6-8’ tall whereas the species grows 6-10’. Foliage is glossy dark green with a pubescent gray-green underside during the summer, turning bright red in the fall. The bright red fall color rivals that of the invasive Euonymus alatus (burning bush), making it a good native, non-invasive alternative. The small, five-petaled flower occur in corymbs and are white to light pink. The glossy red fruit also appears in clusters. ‘Brilliantissima’ fruit is larger, glossier, and more abundant than the species. The common name chokeberry refers to the astringent nature of the fruit. Aronia arbutifolia is best grown in average soil in full sun to part shade and is tolerant of wet soil, making it a good selection for rain gardens. It’s natural suckering habit makes it ideal for naturalized areas, but it can be maintained by removing root suckers. Also effective in mass plantings. Aronia arubutifolia is a nectar source for bees as well as a larval host for several moth species.

Closely related is Aronia melanocarpa, or black chokeberry. A. melanocarpa is also an eastern US native shrub, but is smaller than A. arbutifolia, growing 3-6’ tall and wide. Flowers are similar to A. arbutifolia. The black fruit is about the size of a blueberry and shares the bitter taste of the red chokeberry. Growing conditions are the same as for A. arbutifolia. The smaller size make it good for shrub borders and smaller gardens. Newer cultivars such as ‘UCONNAM165’ (Low Scape Mound) and ‘UCONNAM012’ (Groundhog) are low growing forms that are great options for smaller landscapes. Aronia melanocapra is another early source of pollen and nectar for bee species.

Traditionally grown for fruit production, Vaccinium corymbosum (highbush blueberry) deserves a place in the landscape for its ornamental features. Corymbs of pendulous urn-shaped white flowers are present in the spring. Blueberries emerge in summer, providing ornamental appeal as well as a tasty treat if the birds don’t eat them first. Fall color is a mix of red and purple. Plants are best grown in acidic soil in full sun to part shade. Cross pollination is needed for the best fruit crop. Vaccinum species support both pollinators and wildlife in the landscape. Culativars offer different size berries and different ripening timing. ‘Bluecrop’ has light blue berries that ripen mid to late July; ‘Elliott’ has very late season berries which ripen in August – September; ‘Patriot’ has medium blue berries that ripen in late June.

Also on the market is the Bushel and Berry series of blueberry which offers smaller plants (many around 2’ tall) that work well for smaller landscapes and containers. 'Peach Sorbet' has new growth that emerges with shades of pink and orange maturing to green; 'Pink Icing' spring foliage has pink and red hints before turning green with fall color that turns a unique shade of dark lavender blue; 'Jelly Bean' blueberries are reported to taste like blueberry jelly. Foliage had hints of red in northern climates during the year and yellow to red fall color.

Flowers, foliage, and fall color bring together the next group. The unique bottlebrush flowers of Fothergilla gardenii emerge before the leaves in late April to early May. F. gardenii is a small shrub native to the Southeastern United States; it grows 1.5-3’ tall and 2-4’ wide. Leaves have a unique shape with marginal teeth from the midpoint to the apex and a rounded base. Leaves are blue-green to green in summer and a beautiful mix of yellow, orange, and red in fall. Plants grow best in an acid soil in full sun to part shade. Although flowers are best in full sun, afternoon shade is beneficial in hot, dry summers. The small size makes F. gardenii a great choice for smaller landscapes. It can be used as a specimen or in groups. If a larger plant is desired, Fothergilla major has similar ornamental attributes with a large size (6-10’ tall x 5-9’ wide), larger flowers, and larger leaves.

Flowers, foliage, and fall color bring together the next group. The unique bottlebrush flowers of Fothergilla gardenii emerge before the leaves in late April to early May. F. gardenii is a small shrub native to the Southeastern United States; it grows 1.5-3’ tall and 2-4’ wide. Leaves have a unique shape with marginal teeth from the midpoint to the apex and a rounded base. Leaves are blue-green to green in summer and a beautiful mix of yellow, orange, and red in fall. Plants grow best in an acid soil in full sun to part shade. Although flowers are best in full sun, afternoon shade is beneficial in hot, dry summers. The small size makes F. gardenii a great choice for smaller landscapes. It can be used as a specimen or in groups. If a larger plant is desired, Fothergilla major has similar ornamental attributes with a large size (6-10’ tall x 5-9’ wide), larger flowers, and larger leaves.

Although it doesn’t get as much attention as Hydrangea macrophylla or H. paniculata, Hydrangea quercifolia is worthy of a spot in the landscape. Oakleaf hydrangea grows 6-8’ tall and wide and is native to the southeastern US. The common and species names come from the resemblance of the leaf shape to those of Quercus (oak). Flowers are long panicles of white flowers, similar in appearance to some cultivars of H. paniculata. Leaves are dark green in summer, turning to a mix of red, orange, and reddish purple in fall. Mature branches have exfoliating bark that provides winter interest. Winter hardiness can be a problem in USDA hardiness zone 5 and a sheltered location is needed to help protect flower buds. Temperatures below -10o F can cause loss of flower buds or can cause the plant to die back to the ground. Flowers are formed on old wood and plants should be pruned immediately after flowering. Oakleaf hydrangea can be used as a landscape specimen, accent, or in groups. There are a number of cultivars offering different features: ‘Brido’ (Snowflake) has large pyramidal flower panicles with mostly sterile double white flowers; ‘Munchkin’, ‘Pee Wee’, and ‘Little Honey’ are all dwarf forms. ‘Little Honey’ also has leaves that emerge golden yellow, slowly fading to chartreuse over the summer before finally becoming green in fall before the showy red foliage arrives. ‘Ruby Slippers’ is another compact form that has flowers that emerge white but quickly turn to pink and mature to ruby red.

Looking for a flowering shrub tolerant of heavy shade? Itea virginica (Virginia sweetspire) could be the plant for you! An Eastern US native, the species is a rounded, spreading shrub growing 3-5’ tall and wide. Drooping racemes of fragrant, small white flowers cover the plant in late spring to early summer. The oval leaves are dark green in summer, turning a vibrant mix of red, orange, and gold in fall. When red dominates, Virginia sweetspire can compete with burning bush with its showy fall display. This adaptable plant prefers a medium well-drained soil in full sun to part shade but can tolerate wet soil and heavy shade. It is important to note however that deeper shade reduces the flowering impact. Amazing in mass, but equally effective as a specimen. Cultivars include ‘Sprich’ (Little Henry) which offers a smaller size (2-3’) and better flowering and fall color, ‘Henry’s Garnet’ which also has larger flowers and better fall color, and ‘SMNIVMM’ (Fizzy Mizzy) which has unique upright flower racemes.

A plethora of ninebark have arrived on the market in the last decade. The species, Physocarpus opulifolius, is a central and eastern US native. It is an upright, spreading shrub growing 5-9’ tall and 4-6’ wide. Clusters of small white to pink flowers occur along branches in late spring. Leaves of the species are 3-5 lobed and green in summer without good fall color. Mature branches have exfoliating bark that provide winter interest. Plants grow well in full sun to part shade and are tolerant of dry soil conditions. Light pruning should occur immediately after bloom. Overgrown plants can be trimmed back hard in winter to rejuvenate the plant. The large size of the species makes it a better choice for the shrub border, but smaller cultivars are more at home in landscape beds. Although the leaves of the species are not all that exciting, cultivars offer a variety of leaf colors from yellow to copper orange to deep purple. ‘Diabolo’ is similar is stature to the species but with deep purple leaves. ‘Seward’ (Summer Wine) and ‘SMPOTW’ (Tiny Wine) also offer deep purple foliage but smaller sizes. ‘Mindia’ (Coppertina) is a compact form with copper spring foliage that turns red by summer. ‘Dart’s Gold’ has foliage that emerges bright yellow in spring slowing fading to lime green in summer with yellow fall color. Flowers of cultivars are similar to that of the species. Flowers of ninebark are attractive to pollinators. If supporting insects is a priority, it should be noted that purple leaf varieties have been shown in research to be less attractive to leaf eating caterpillars than the species.

The previously mentioned species are all native to North America. The following selection is of non-native species appropriate for New England landscapes.

Only fairly recently becoming available in the trade, Heptacodium miconoides (seven-son flower) warrants consideration for the landscape. This is a large shrub to small tree with a fountain shape growing 10-15’ tall and 10’ wide that can serve as an excellent specimen in the landscape. Terminal panicles of fragrant white flowers arrive in late summer to early fall. Flowers are followed by purplish-red fruits with rose-pink calyces that persist into fall. Winter appeal is provided by the exfoliating bark. Although not a native, H. miconoides is a good fall source of nectar for butterflies and hummingbirds. Plants tolerate a wide range of soil and prefer full sun.

Pendulous racemes of creamy yellow bell shaped flowers with pink-red veins provide the common name of redvein enkianthus for Enkianthus campanulatus. Native to Japan, Enkianthus is an upright shrub growing 6-8’ tall and 4-6’ wide. During the summer, leaves are green to bluish green in whorls around the ends of the branches. When fall color is good, it has vibrant red leaves with a mixture of yellow, orange, and purple highlights. Plants are best grown in full sun to part shade and are at home with other acidic loving plants such as Rhododendron.

Another genus that belongs on the list of multi-season standouts that isn't covered here is Viburnum. Spring blooms, dazzling berries, and good fall color describe many of the species (although not all Viburnum species have a good berry set or fall color). Instead of highlighting a particular Viburnum, I will note that Viburnum leaf beetle susceptibility should be considered when choosing a Viburnum for the landscape, as plants can be considerably damaged. Please refer to the UMass Extension Fact Sheet on Viburnum leaf beetle for information on the beetle, control, and plant susceptibility.

Although these plants are by no means exclusive of the multi-season standouts that can grace our landscape, it is a great place to start when looking for a new addition to the plant palate.

Mandy Bayer, PhD, Horticulturist and Landscape Plant Specialist

A Note for Growers on the May 18, 2023 Freeze Event

Massachusetts experienced a widespread, late-season freeze on the morning of May 18. While there are broad concerns about damage to agricultural crops that have made headlines, some producers of ornamental crops were adversely affected as well. Growers that have related crop losses that exceed 30% may be eligible for emergency assistance. Note that in order to qualify, an operation must have 50% or more of production "on farm", and finished crops purchased for resale are not eligible. Contact the Farm Service Agency office in your county: https://offices.sc.egov.usda.gov/locator/app?state=ma&agency=fsa

Upcoming Events

For details and registration options for these upcoming events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

- 6/27/23 - Insects and Ornamentals Walkabout, New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill, Boylston MA, 2:00-4:00 pm.

1 pesticide contact hour for categories 36 and Applicator's (Core) License; 2 ISA, 1 MCA, 1 MCLP, and 1 MCH credits available. - 7/19/23 - UMass Turf Research Field Day, South Deerfield MA, 9:00 am - 1:00 pm.

2 pesticide contact hours for categories 37, Dealer, and Applicator's (Core) License; 1 MCLP, 1 MCH, and 0.25 CGCS education points and credits available.

Pesticide Exam Preparation and Recertification Courses

These workshops are held virtually. Contact Natalia Clifton at nclifton@umass.edu or go to https://www.umass.edu/pested for more info.

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources

TickTalk webinars - To view recordings of past webinars in this series, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples. By mail is preferred, but clients who would like to hand-deliver samples may do so by leaving them in the bin marked "Diagnostic Lab Samples" near the back door of French Hall. The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. See our website for instructions on sample submission and for a sample submission form at http://ag.umass.edu/diagnostics.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The lab is accepting orders for Routine Soil Analysis (including optional Organic Matter, Soluble Salts, and Nitrate testing), Particle Size Analysis, Pre-Sidedress Nitrate (PSNT), Total Sorbed Metals, and Soilless Media (no other types of soil analyses available at this time). Testing services are available to all. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Tick Testing - The UMass Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing options at: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources.