Periodical cicadas were known to the native peoples of North America for centuries before Europeans arrived, but first recorded by European settlers in 1634. These insects are a wonder of nature, and should be respected and studied with awe; however, for a short time, they may feel like "pests" to some. Periodical cicada species emerge every 13 to 17 years, depending upon the species. 17-year cicada species, such as those representing Brood X, include Magicicada septendecim, M. cassini, and M. septendecula. 13-year cicada species include Magicicada tredecim, M. neotredecim, M. tredecassini, and M. tredecula. Some cicadas emerge later than the majority of the brood, and may be found the year after a very large emergence in an area - however, these are typically eaten very quickly by predators. For parts of Massachusetts, historically, Brood XIV is the one that we need to watch, which is on track to emerge again in 2025. (Brood XIV is regionally distributed across KY, GA, IN, MA, MD, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, TN, VA, and WV and was last active in 2008.)

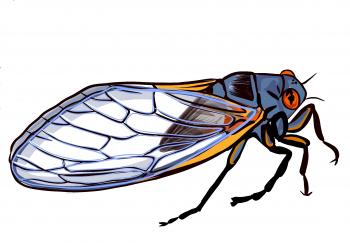

The immature stages of these insects live on the roots of trees and shrubs, growing very slowly. In the case of 17-year cicada's (such as Brood X which was recently active in 2021), in the 17th year of their life they will emerge from the soil, usually in late-May to early-June. As they emerge, they can climb trees, buildings, and all other manner of upright structures. They shed their nymphal skins (many of which remain visible to observers, stuck to these objects) and adults move to the trees. Adults will conduct a bit of feeding, and males make their well-known “buzzing” sound to attract females to mate (only males sing). Females will then use their ovipositor (egg-laying structure) to insert their eggs into the twigs of trees and shrubs (laying up to 600 eggs). Six to ten weeks later, those eggs will hatch, and nymphs will move to the ground where they will dig into the soil and begin feeding on host plant roots. After that time, their underground stages will go largely unnoticed until the next adult emergence event.

In addition to periodical cicadas, Massachusetts is home to dog-day cicada species (Tibicen spp.). These are the largest cicadas in North America, and are much less commonly observed (but frequently heard). Males make the loud, long, buzzing sounds that mark our summer days. These species are sometimes called annual cicadas, as the adults emerge each year. Nymphs take 2-5 years to develop, but overlapping generations result in annual adult appearance.

Periodical cicadas cause injury to a wide variety of deciduous trees and shrubs, but oaks are primary hosts. Females cause damage when they lay a series of small groups of eggs (inserting them into twigs). Small branches or twigs may be girdled or killed by this process. The damage may also predispose the impacted branches to breakage and allow for easy-access by pathogens. Adults feed on the fluids they extract from twigs, and the nymphs feed in a similar manner on the roots of trees. Injury as a result of this feeding is considered to be minor. Broods of periodical cicada adults have synchronized emergence events every 13 or 17 years. These events can be loud and very noticeable to the public. Many people incorrectly categorize periodical cicadas with Biblical locusts. An important thing to remember about periodical cicadas is that they are native to North America and have evolved with our forests. Some research suggests that they are natural pruners of trees, their oviposition damage actually leading to fuller canopies by removing branch tips. When they die, the adult cadavers return nutrients to the soil. Mammals and birds eat them. Periodical cicadas often do not seriously damage their hosts, and are present so infrequently, and co-evolved with our forests, that management is not necessary.

Brood XIV is expected to emerge in parts of Massachusetts in 2025. Watch for nymphs to emerge from the soil by late-May or early-June. At that time, the nymphs will crawl up upright structures and shed their skins (molt) and emerge as adults. Watch for flagging host plant branches as a result of the damage caused by egg laying adult females.

Mesh netting (no larger than 1/2 inch openings) is a good way to protect newly planted, smaller trees during a periodical cicada emergence year. This is only necessary if it is certain that the planting is in an area, during a year, that is expecting emergence. Netting needs to be placed on trees prior to cicada emergence, and kept on them for the 4-6 weeks of expected cicada activity. If possible, avoid transplanting trees in the fall and spring the year prior in areas where a periodical cicada emergence is expected. Also wait to prune trees where females are expected to oviposit (lay their eggs) until after the emergence has occurred.

A wide variety of predators will take advantage of the periodical cicada feast when it becomes available. However, predators are often oversaturated (there are not enough predators to eat all of the cicadas) during an emergence year, so the population is not reduced. This is the ultimate strategy of the cicadas, to emerge in force to avoid predation. Certain species of birds will feed on periodical cicadas (grackles, crows, etc.) and fish will even eat periodical cicadas that emerge near streams. In fact, certain species of birds may experience significant fluctuations in their populations during and post periodical cicada emergence (Koenig and Liebhold, 2005).

Periodical cicadas experience a fungal infection by Massospora cicadina, which has a life cycle such that adult cicadas can become infected by the fungus, followed by the next generation of cicada nymphs. The fungus impacts the adult periodical cicadas such that their behaviors become more attractive to other adults, increasing the likelihood of transmission of the fungus between individuals.

Bifenthrin (NL)

Carbaryl (L)

Chlorpyrifos (N)

Cyfluthrin (NL)

Imidacloprid (L)

Lambda-cyhalothrin (L)

Pyrethrins + piperonyl butoxide (L)

Zeta-cypermethrin (L)

Chemical management or physical barriers, such as netting, usually only required on younger trees. Chemical management of periodical cicadas may be difficult, and impractical, and is generally not recommended. However, there are products available containing the above active ingredients labeled for use against periodical cicadas in Massachusetts.

When used in a nursery setting, chlorpyrifos is for quarantine use only.

Make insecticide applications after bloom to protect pollinators. Applications at times of the day and temperatures when pollinators are less likely to be active can also reduce the risk of impacting their populations.

Note: Beginning July 1, 2022, neonicotinoid insecticides are classified as state restricted use for use on tree and shrub insect pests in Massachusetts. For more information, visit the MA Department of Agricultural Resources Pesticide Program.