Jumping/Crazy/Snake Worms – Amynthas spp.

Identification

Jumping worms are smooth, glossy, and dark gray/brown in color. A mature adult is 4-5 inches long. (However some sources note that these species can be 1.5 – 8 inches in length during their lifetime.) Their clitellum (a lighter colored band around the worm) is cloudy-white to gray in color and completely wraps around the body of the worm. The surface of the clitellum is also flush with the body. The clitellum is found relatively close to the head of the worm, approximately 1/3 the total length of the worm from the head. Adult worms are firm and not coated with a slimy substance. They will thrash violently when disturbed, and are often found in large groups of individuals. Jumping worms do not burrow deep into the soil and are typically found on the soil surface in debris or leaf litter. However, jumping worms may be found in various habitats, such as yards, gardens, forests, mulch, compost, potted plants, and other similar areas. The observations from many states suggest that these worms prefer moist areas with high organic matter content, and are most commonly found on properties next to forested, wooded areas, flower beds, and in raised garden beds.

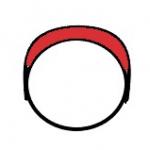

Sometimes Asian earthworms are confused with other species (at least 21 species of earthworms occur in Massachusetts: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/earthworms-in-massachusetts-history-concerns-benefits. The most common and visible species are Lumbricus terrestis, or nightcrawlers. Nightcrawlers tend to be pink or reddish in color with a dark head and pale body. They are relatively big. Mature nightcrawlers can be 6-8 inches in length, and have thick, slimy, and floppy bodies. They wiggle and stretch when disturbed, and do not tend to thrash violently or move in a snake-like manner. They can be perceived as slow and sluggish compared to Amynthas spp. Nightcrawlers (adults and immatures), especially Lumbricus terrestis tend to flatten their tail when they move, which is commonly used for initial identification. Their clitellum is reddish or pink in color, slightly raised from the rest of the body, and only partially surrounds the body, much like a saddle. The shape, color and position of the clitellum are important for proper identification (Figure 1), as shown in this picture of a jumping worm.

Sometimes Asian earthworms are confused with other species (at least 21 species of earthworms occur in Massachusetts: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/earthworms-in-massachusetts-history-concerns-benefits. The most common and visible species are Lumbricus terrestis, or nightcrawlers. Nightcrawlers tend to be pink or reddish in color with a dark head and pale body. They are relatively big. Mature nightcrawlers can be 6-8 inches in length, and have thick, slimy, and floppy bodies. They wiggle and stretch when disturbed, and do not tend to thrash violently or move in a snake-like manner. They can be perceived as slow and sluggish compared to Amynthas spp. Nightcrawlers (adults and immatures), especially Lumbricus terrestis tend to flatten their tail when they move, which is commonly used for initial identification. Their clitellum is reddish or pink in color, slightly raised from the rest of the body, and only partially surrounds the body, much like a saddle. The shape, color and position of the clitellum are important for proper identification (Figure 1), as shown in this picture of a jumping worm.

| Characteristic |

JUMPING/“Crazy” worms |

NOT JUMPING/“crazy” worms |

|---|---|---|

| Overall color of the body | Entire body has a pigmentation, usually dark in color (brownish, greyish). | At least some parts are pale; night crawlers might have a dark-colored head and upper/dorsal part of the body, but the underside and tails are light colored; entire body of some species is pale. |

| Clitellum color |

Distinctly white or much lighter than color of the body. |

Somewhat similar to color of the body. |

| Clitellum type |

Annular clitellum, encircling the worm’s body. |

Saddle-like clitellum, very distinct on the upper side, flattens on the underside. |

| Position of the clitellum |

Clitellum close to the head. |

Clitellum farther away from the head. |

| Movement | Snake-like movement, thrashing S-patterned movement. |

Slower, move by stretching the body segments and pulling the rest of the body to the head; some species might coil when disturbed, nightcrawlers flatten the tail. |

| Soil characteristics | Coffee grounds or like “Nerd©” candy in appearance. | |

| Seasonality/ Peak of adult activity | Most adults are observed in August - September. | Adults are active in early spring and the fall. |

Life Cycle

The life cycle of these jumping worms, and timing specific to Massachusetts, is not completely understood. In the springtime (April-May) the overwintered eggs (found in cocoons) hatch in the top 1-4 inches of soil. During the summer months, the worms feed and grow. When immatures hatch, it is almost impossible to see them. They become noticeable (if searched for) only in mid to late May. The first adults appear in the end of May – June, but the numbers are low and infestations are rarely noticed at that time. It is easy to misidentify earthworms if only immatures found. By August and September, this is when most observations of fully mature jumping worms occur. At that time, snake worms become quite abundant, infestations become very noticeable, and cause a lot of concern for property owners and managers.

Mature adults reproduce parthenogenetically (do not need a mate to reproduce) and deposit egg-filled cocoons into their surroundings. It is not currently known how many eggs each adult can lay in the wild, however in laboratory settings, up to 30 cocoons with 2 eggs each have been observed. Frost kills the adults, and the egg-filled cocoons (which are about the size of a mustard seed) overwinter. Cocoons are resistant to the cold and drought conditions. They are very difficult to detect due to their tiny size, and dirt-like color. As such, they can be very easily moved in soil, mulch, compost, potted plants, etc. Physically removing jumping worm cocoons is impractical.

Prevention

Unfortunately, there are currently no curative management options available for property owners and managers dealing with existing jumping worm infestations. There are no pesticides labelled for earthworm management in the United States, so no products can be legally used for this purpose. Therefore, prevention is essential. Some preventative measures that concerned citizens can utilize include but are not limited to:

- Learn how to recognize jumping worms and teach your family, friends, colleagues, etc.

- Look for jumping worm adults and their grainy, dried coffee ground-like castings. Not seeing the adults on the substrate surface, but have reason to believe they may be there? Try mixing a gallon of water and 1/3 cup of ground yellow mustard seed and pouring that slowly over the soil/area with suspicious castings. If present in that location, the worms will be irritated (not killed) and brought to the surface where they can be collected for identification. (Note: this is not a means of managing these earthworms, but merely a tool that can possibly be used for detection.)

- Do not purchase worms advertised as jumping worms, snake worms, Alabama jumpers, or crazy worms for any purpose (ex. composting or fishing baits).

- Anglers: never dispose of unused fishing baits into the environment. Always throw away unwanted bait worms in the trash.

- Gardeners: look for evidence of jumping worms in soil, compost, mulch, potted plants, etc. If you see coffee ground-like castings in these materials or notice jumping worm adults, identify them using the above guide. Try not to move materials known to contain jumping worms to new locations. Specifically, reduce human aided long distance disperal of jumping worms, if possible. Jumping worms have been observed to move up to 40 ft. per year on their own (natural dispersal).

- Composters: heat materials to the appropriate temperatures and duration following protocols that reduce pathogens. Recent research suggests that heating* the cocoons of jumping worms to somewhere around 104°F for 3 days will kill the egg-containing cocoons. *Note: UMass Extension has received many questions about solarizing home gardens or raised beds. Research into this is ongoing, and there are still many questions regarding what steps need to be taken to achieve optimal results. We currently do not have step-by-step instructions for using solarization to manage jumping worms in the landscape.

What to do if you already have jumping worms on your property?

- Do not panic. If the worms are located on your property, take precautions to prevent moving them to new geographic locations. However, natural dispersal of jumping worms will occur over time, and there is no way to eradicate them once they are established in a location.

- Remove and destroy any adult jumping worms if you see them. This can be done by dropping them into a bucket of soapy water or sealing them in a plastic bag.

- Do not attempt to manage the worms with chemicals or products that are not labelled for that purpose. Currently, there are no pesticides or approved methods to manage jumping worms. Using products without this use explicitly included on the label is illegal.

Further Resources:

Invasive Insect Webinar Series Featuring Dr. Olga Kostromytska, University of Massachusetts - Invasive Earthworms in Massachusetts – Biology, Impacts, and Research Updates

Cornell University Cooperative Extension fact sheet - Jumping Worms

Plant and Soil Science Dept., University of Vermont - Amynthas agrestis: The Crazy Snake Worm

University of Minnesota Extension - Jumping Worms

University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension - Invasive in the Spotlight: Jumping Worms

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources - Jumping Worms

References

Blackmon, James H. et al. “Temperature Affects Hatching Success of Cocoons in the Invasive Asian Earthworm Amynthas agrestis from the Southern Appalachians.” Southeastern

Naturalist 18 (2019): 270 - 280.

Written by: Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program and Dr. Olga Kostromytska, Entomologist and Extension Assistant Professor, Stockbridge School of Agriculture