Section 5: Disease Management

In this section:

Scouting for turf diseases

The following key is patterned after Shurtleff (1987) in “Controlling Turfgrass Pests” but has been adapted to turfgrass diseases common in Massachusetts. The four sections include COLD, COOL/WARM, and HOT temperature diseases as well as problems not generally related to temperature.

Technical terminology has been minimized. The word “mycelium” (or hyphae) refers to the web-like growth of fungi on turf when wet. “Black specks” are the spore containers produced by a few of the disease causing fungi. “Sclerotia” are dark, pinhead-sized or slightly larger masses of mycelium that some fungi produce as survival structures.

How to use this key

Decide first the temperature when symptoms first appeared. Then read the subsections to decide which best describes the problem. Symptoms of diseases are often quite different on lawns than on highly maintained, low-mown turf such as putting greens. The most common diseases are indicated by a star (★).The diagnosis of turf diseases can be difficult even in the laboratory. Use this key only as a general guide. For information about disease diagnostic services available from UMass, refer to the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab at ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory.

Section I. Cold Weather (32–45°F) Diseases and DisordersA. Irregular patterns or streaks in turf.

B. Turf killed (rotted or straw-colored) in wettest areas.

Section II. Cool-to-Warm Weather (45–75°F) DiseasesA. Circular patches or rings in turf after grass greens up in spring.

B. Irregular patterns (usually) in turf.

Section III. Hot Weather (over 75°F) DiseasesOccur from late spring to late summer.

A. Circular patterns in turf.

B. Irregular patterns of weak, thin, dormant or dead grass. Large areas appear dry, then wilt, and turn brown.

Section IV. Other Causes of Poor Turf Usually Independent of Temperature.A. Turf gradually becomes pale green to golden yellow and grows slowly; stand often thins out.

B. Turf suddenly appears scorched.

C. Round to irregular patches of dead or dormant grass; often follows dry periods. BURIED DEBRIS, INSECT INJURY or THICK THATCH D. Turf bare or thinned; often in traffic areas, dense shade, waterlogged soil, etc.

E. Turf dry, bluish green (footprints visible), wilts may later turn brown. DROUGHT, WILT or IMPROPER WATERING |

Cultural management of turf diseases

Though it can be challenging to maintain intensively-managed turfgrass without fungicides, good cultural practices will reduce the need for fungicide applications and make necessary applications more effective. In fact, effective and well-timed cultural practices may minimize or eliminate the need for fungicide applications in lawns and other less intensely maintained turfgrass areas.

Starting right

Prepare the site well. Remove stumps, construction materials and other debris. Improve drainage where necessary, and fill in low areas. Test soil pH and adjust to 6.0 to 7.0 if required. Break up soil clumps to provide a uniform area for seed or sod.

Choose seed or sod carefully (see Turfgrass Selection: Species and Cultivars). Inspect sod for diseases or other problems. Choose high quality, pathogen-free seed. Many disease resistant cultivars are now available and should be included in blends and mixtures. Genetic variability in turfgrasses will reduce the chance for epidemics that kill or damage large areas of turf.

General landscaping decisions can have significant impacts on turf health. Pruning of tree branches may increase light penetration to allow better turfgrass growth. Trees, shrubs, and other plantings should be placed to allow good air circulation, so turf will dry quickly after rain or dew. In very shady areas, shade-tolerant turfgrass cultivars or other groundcovers should be planted.

Seed should be planted only in well prepared soil with good drainage when temperatures stay in the range to allow rapid germination and establishment. Keep soil and seed moist, but do not over-water.

Routine Care

Fertilizers - Apply according to current recommendations and based on a soil test. Excess nitrogen will cause succulent growth that is more susceptible to disease. Avoid nitrogen applications (especially water soluble/quick-release fertilizers) during leaf spot season early in spring, during hot, humid weather, and just before dormancy in fall, which may leave turf more susceptible to snow molds and winter injury. Be sure, however, to meet the minimum nitrogen requirement for the turfgrass species and use as some diseases (e.g. red thread, rusts, and dollar spot) are encouraged when nitrogen is deficient.

Herbicides - Herbicides can stress turfgrasses and make them more susceptible to diseases. Apply carefully according to label directions and with attention to environmental conditions.

Some herbicides may have fungistatic effect and provide some degree of disease control. Noting fungistatic occurrences may be useful for reducing the amount of fungicide applied, by applying fungicides in combination with fungistatic herbicides.

Liming - Adjust pH according to soil test recommendations. Disease occurrence may increase at pH extremes (too high or too low). Lime applied late in autumn can increase Microdochium patch (pink snow mold) incidence and high pH can predipose turf to take-all patch infection during the spring.

Mowing - Mowing wounds turfgrasses and can spread pathogens (disease-causing organisms). Minimize wounding and shredding of grass blades by keeping mower blades sharp and adjusted properly. If possible, mow when the turf is dry. Mow as high as possible for species and the turf use, using the maximum mowing height in hot weather. Avoid mowing more than one-third of the total height at each cutting to reduce stress to the root system. Mowing in autumn until turf stops growing can help to reduce damage from snow molds.

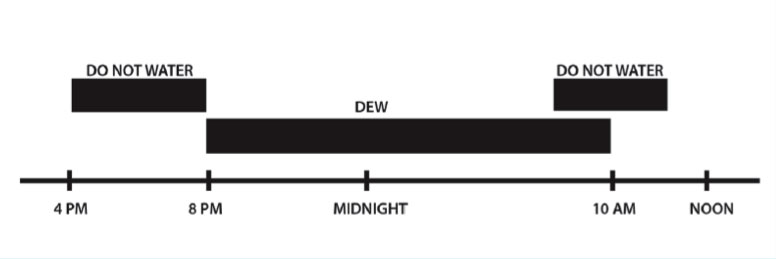

Watering - Water is necessary for good plant growth, but too much water floods open spaces in the soil, depriving roots of oxygen. Disease-causing fungi reproduce by spores that, like seeds, need water to germinate and infect turf. Dry turfgrass blades reduce disease by reducing infection. Deep and infrequent watering is strongly preferred to shallow, frequent watering to minimize leaf wetness and to encourage an extensive root system. Every effort should be made to not extend the duration of time blades are wet from dew or irrigation. Do not water in late afternoon or early evening. Night irrigation after dew appears may help conserve water, but is not recommended on hot, humid nights because it can increase some diseases (Figure 2). Avoid light, frequent sprinklings (syringing) except to prevent wilting in close-cut or shallow rooted turf and during hot, dry weather. In certain situations, keeping upper soil layers moist may help to reduce the occurrence of necrotic ring spot and summer patch.

Figure 2. When NOT to water turf

Thatch - Thatch is mostly composed of partially decayed above- and below-ground lateral stem tissue (stolons and rhizomes). A thin layer is beneficial in most turf situations. When thatch is more than 1/2” thick, it reduces nutrient and water absorption and harbors insect pests and disease pathogens. Prevent excessive thatch formation by providing adequate fertility in combination with aeration, verticutting and topdressing when needed. Mechanical removal of thatch is disruptive and should be accomplished in spring and late summer when time and conditions will allow for sufficient turf recovery.

Compaction - Several diseases (e.g. necrotic ring spot, summer patch, or athracnose basal rot) are worse in areas with compacted soil. Core aeration can help relieve soil compaction and improve turf quality. On some sites, traffic management may also be appropriate to minimize soil compaction.

Targeted cultural practices

Some sites have a history of disease problems, while others exist in a growing environment conducive to certain diseases. For some pathogens, targeted cultural practices can go a long way towards preventing disease occurrence, reducing severity of disease when it does occur, and promoting recovery from damage. Table 18 details cultural management strategies for some of the most common turf diseases encountered in the Northeast.

Table 18. Cultural management strategies for common turf diseases.

| Disease (Pathogens) | Turfgrass Hosts* | Season | Cultural Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algae, Mosses | all turfgrasses | Apr – Nov | Improve fertility and drainage. Alleviate compaction. Modify shade-causing agents to increase light penetration. |

|

Anthracnose (Crown/Basal Rot) |

bentgrasses, annual bluegrass | Mar – Sept | Provide adequate N fertility. Avoid stress from too little or too much water and compaction. Raise mowing height. |

| Bentgrass Dead Spot Ophiosphaerella agrostis | bentgrasses less than 6 years old on sand-based root zones. | June – Sept | Add N. Rake out and reseed. |

|

Brown Patch |

all turfgrasses, tall fescue, bentgrasses, perennial ryegrass | July – Sept | In hot weather, avoid excess N and excess water. Avoid night watering. Remove dew from putting greens. |

|

Brown Ring Patch (Waitea Patch) |

annual bluegrass, rough bluegrass, creeping bentgrass | Dec – July | Apply adequate N for rapid recovery from damage. Dethatch and improve drainage. Symptoms can often be masked with N or iron. |

|

Copper Spot |

bentgrasses | June – Sept | Avoid excess N. Minimize leaf wetness. Plant resistant cultivars. |

| Damping-off, Seed Rot several fungi including Pythium spp., Fusarium and Rhizoctonia solani |

all turfgrasses | Apr – Oct | Ensure careful seedbed preparation. Use good quality seed. Maintain soil moisture but avoid overwatering. |

|

Dollar Spot |

all turfgrasses, bentgrasses, annual bluegrass | June – Sept | Avoid N deficiency and water stress. Minimize leaf wetness. Relieve compaction and excess thatch. Raise mowing height. |

| Downy Mildew (Yellow Tuft) Sclerophthora macrospora | all turfgrasses | May – Sept | Avoid excess N and excess watering. Iron sulfate may mask symptoms. Improve drainage. |

| Fairy Ring (various fungi) | all turfgrasses | April – Nov | Mask symptoms with N or iron. Core aerate and water. Fumigate or remove soil in severe cases. |

|

Gray Leaf Spot |

perennial ryegrass, tall fescue | July – Nov | Avoid excess N. Minimize leaf wetness. Reduce shade, lower mowing height. |

|

Leaf Smuts |

bentgrasses, Kentucky bluegrass | April – Nov | Avoid excess N in spring. Avoid water stress. Plant resistant cultivars. Collect clippings and discard. |

| Leaf Spots and Blights/ Melting Out “Helminthosporium” spp. Ascochyta, Bipolaris, Curvularia, Drechslera, Nigrospora, Septoria, Leptosphaerulina |

all turfgrasses, Kentucky bluegrass, bentgrasses, fine fescues | April – Oct | Avoid excess N, especially in spring. Raise mowing height. Minimize leaf wetness. Plant resistant cultivars. |

| Necrotic Ring Spot Ophiosphaerella korrae | Kentucky bluegrass, esp. sod (3-4 yrs old), fine fescues, annual bluegrass | June – Sept | Avoid water and fertility stress. Avoid compaction and excess thatch. Utilize slow release N sources. |

|

Powdery Mildew |

Kentucky bluegrass, fine fescues | July – Sept | Reduce shade and increase air circulation. Avoid excess N. |

|

Pythium Blight |

all turfgrasses, perennial ryegrass, bentgrasses | June – Aug | Avoid excess N and night watering in hot weather. Do not mow when wet or when disease is active. Improve drainage and air circulation. |

| Pythium Root Dysfunction Pythium volutum | creeping bentgrass | Sept – June | Avoid excess N. Improve drainage. Aerate Regularly. |

|

Pythium Root Rot |

all turfgrasses, bentgrasses and annual bluegrass in sand greens | Mar – Nov | Improve drainage. Increase soil organic matter. |

| Red Thread Laetisaria fuciformis and Pink Patch Limonomyces roseipellis | all turfgrasses, perennial ryegrass, fine fescues | April – Oct in mild, wet weather | Avoid N deficiency, water stress, and low pH. Minimize leaf wetness. Water deeply and infrequently. Improve light penetration and air circulation. |

|

Rusts |

all turfgrasses, Kentucky bluegrass, perennial ryegrass | July – Oct | Avoid N deficiency and water stress. Minimize leaf wetness. Plant resistant cultivars. Reduce thatch. Raise mowing height and collect clippings. Water deeply and infrequently. |

|

Slime Molds |

all turfgrasses | June – Sept | Mow or hose away. Fungicide applications are not necessary. |

| Snow Molds: Pink Snow Mold (Microdochium Patch) Microdochium nivale and Gray or Speckled Snow Mold (Typhula Blight) Typhula spp. | all turfgrasses, bentgrasses | Nov – April | Avoid lush growth in fall. Continue mowing until autumn growth ceases. Avoid prolonged snow cover; do not allow excessive piling of snow on turf and reduce drifting with placement of snow fences. Fertilize lightly in spring to promote re-growth. |

|

Summer Patch |

fine fescues, annual bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass | July – Sept | Avoid water stress and overwatering. Avoid compaction. Maintain adequate fertility. Lower pH in top inch of soil. Raise mowing height. Utilize slow release forms of N. Apply 2 lb/A MnSO4 annually in spring. |

|

Take-all Patch |

bentgrasses | Mar – June Sept – Nov | Avoid heavy lime applications. Lower pH in top inch of soil. Improve drainage. Apply acidifying fertilizers. |

|

Yellow Patch (Cool Weather Brown Patch) |

bentgrasses, Kentucky bluegrasses, perennial ryegrass | Nov – April | Avoid excess N. Minimize leaf wetness. Improve drainage and air circulation. |

| * The most susceptible turfgrass species are in bold italics. | |||

Biological management of turf diseases

At this time, many research programs are investigating biological controls for turf diseases. The two main areas of emphasis are the use of organic composts and the use of specific microbes that inhibit disease-causing fungi. There are some new commercial products for the biological control of turf diseases that consist of specific microbes, and many potential products are currently under study. Several organic composts have exhibited some suppression of certain diseases, but much more research is needed before recommendations can be made. Such composts are thought to contain microbial populations that inhibit disease-causing fungi. Different composts inhibit certain diseases but not others; other composts do not appear to suppress disease at all.

Genetic resistance can also be considered a form of biological control because certain turfgrass cultivars are resistant to or tolerant of some diseases. Selection of disease-resistant cultivars or disease-immune species is a priority in many turfgrass breeding programs. If a certain disease is a continuing problem, it can be helpful to investigate the availability of new disease-resistant cultivars that can be used for over-seeding or reestablishment of damaged areas. See Turfgrass Selection: Species and Cultivars for information on disease tolerant cultivars that are well-adapted to Massachusetts conditions.

There is little doubt that the use of biological control products and improved genetic resistance will become a more significant part of turfgrass disease management in the near future. However, these new alternatives will work best as part of an integrated disease management program that includes a strong cultural approach to reduce stress factors and minimize opportunities for infection by pathogenic fungi.

Characteristics of turf fungicides

Most common turfgrass diseases are caused by fungi. Fungicides kill or inhibit the growth of fungi.

There are two general categories of fungicides:

- contact/protectant

- penetrant

Contact/protectant fungicides remain on the outside of the plant and protect the plant from new infection. They must be applied at comparatively short intervals that can range from 5 to 14 days, because the fungicides are degraded by ultraviolet light, washed from the leaf surface by irrigation or rain, or mowed away. These fungicides do not have curative activity and new growth is not protected. Thorough coverage of plant tissue is critical to successful protection. Examples of contact/protectant fungicides commonly used in turf include captan, chlorothalonil, chloroneb, etridiazole, fluazinam, fludioxonil, mancozeb, maneb, PCNB, and thiram.

Penetrant fungicides are absorbed into plant tissue and may provide some curative action. The duration of control afforded by penetrant fungicides is often much longer than that offered by contact fungicides, and some redistribution into new tissue may occur as the plant grows. Application intervals vary, but often range from 14 to 21 days and longer. According to specific topical modes of action, penetrant/systemic fungicides can be further divided into three sub-categories:

- Localized penetrants form a protective barrier on the plant surface and permeate into the leaf in the area where deposition occurred. These fungicides have some curative activity, but do not move upward or downward inside the plant. Examples include iprodione, polyoxin D zinc, trifloxystrobin, and vinclozolin.

- Acropetal penetrants form a protective barrier on the plant, permeate into the plant, and move upward in the plant’s xylem. These fungicides have protective activity including new growth, and have good curative activity. Examples include azoxystrobin, fenarimol, mefenoxam, and triadimefon.

- Systemic penetrants form a protective barrier on the plant, permeate into the plant, move upward in the plant’s xylem, and move downward in the plant’s phloem. These fungicides have protective activity including new growth, and have good curative activity. Of the currently available penetrant/systemic fungicides, only fosetyl-Al (Aliette Signature) is truly systemic and moves both upward and downward in the plant.

Refer to Table 20 for a list of available fungicide materials and their respective topical modes of action.

Fungicide resistance

Some fungicides are site specific in their mode-of-action. This means that it takes very little genetic change on the part of a fungus for resistance to occur. Resistance may result in poor disease control, meaning that higher application rates or shorter intervals are needed to maintain healthy turf, or complete control failure. Resistance may develop suddenly or gradually depending on the fungicide involved. Once resistance has developed in a fungal population, it may last for a long time or gradually disappear if the fungicide is no longer used, depending on the fungicide and site-specific factors. Resistance is common for some diseases, but not observed for others. Fungicide resistance has been documented for anthracnose, dollar spot, Microdochium patch, gray leaf spot, and Pythium blight.

The best strategy is to try to prevent, or at least delay, resistance. All penetrant fungicides are at risk for resistance development due to their “single-site” mode-of-action. Contact/protectant fungicides are unlikely to result in resistance because most of them have “multi-site” modes-of-action with the exception of fludioxonil (Medallion) and a few others which have a “single-site” mode-of-action. There are multiple chemical groups with different biochemical modes-of-action for broad-spectrum disease control in turfgrass that are at risk for resistance. Fungicide resistance has already been reported in five of these groups (Benzimidazole, Dicarboximide, Demethylation Inhibitor (DMI), Strobilurin (QoI) and Phenylamide).

Table 19. Turfgrass pathogens and chemical classes with documented fungicide resistance.

| Turfgrass Disease (causal agent) | Resistance to chemical classes (see Table 20) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzimidazole | Dicarboximide | DMI | QoI | Phenylamide | |

| Anthracnose (Colletotrichum cereale) | X | X | X | ||

| Dollar spot (Sclerotinia homoeocarpa) | X | X | X | ||

| Gray leaf spot (Pyricularia grisea) | X | ||||

| Microdochium patch/pink snow mold (Microdochium nivale) | X | ||||

| Pythium blight (Pythium aphanidermatum) | X | ||||

Mix or alternate between different site-specific chemical groups or with multi-site contact/protectant fungicides, indicated by different FRAC (Fungicide Resistance Action Committee) code numbers, to prevent or delay the development of resistance. Changing fungicides by brand or trade name will not prevent resistance if the active ingredient or chemical group is the same. Fungicide labels list the active ingredient(s) in smaller letters below the brand name. Be especially careful when using combination (pre-mixed) products, which may include fungicides subject to resistance prevention strategies. Tables 20-22 list fungicide materials along with their corresponding FRAC codes for ease of reference.

Guidelines to prevent or delay resistance to turf fungicidesMinimize disease conditions

Make proper fungicide choices

Know the material

|

Table 20. Chemical classes, trade names and topical modes of action of fungicides registered for use on turf.

| Common Name | FRAC 1 | Group Name | Trade Name(s) | Topical mode of action 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

azoxystrobin |

11 |

Strobilurin (QoI) |

Heritage (50WG, TL, G) |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

boscalid |

7 |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor |

Emerald 70EG |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

captan |

M4 |

Phthamlimides |

Captan (50W, 50WP, 4L), Captec 4L |

Contact |

|

chloroneb |

14 |

Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

Terraneb SP, Teremec SP, Andersons Fungicide V, Proturf Fungicide V |

Contact |

|

chlorothalonil 3 |

M5 |

Chloronitrile |

Andersons 5% Daconil 5G, ArmorTech (825 DF, CLT 720), Concorde SST 6F, Daconil (5G, 2787, Zn, Ultrex, WeatherStik), Echo 720F, Ensign 720, Equus 500ZN, Manicure (6FL, Ultra), Lebanon Daconil 5G, Legend, Pegasus (6L, DFX, HPX) |

Contact |

|

cyazofamid |

21 |

Quinone inside Inhibitors (QiI) |

Segway |

Localized Penetrant |

|

etridiazol (ethazole) |

14 |

Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

Koban, Terrazole 35WP, Truban |

Contact |

|

fluazinam |

29 |

Uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation |

Secure |

Contact |

|

fludioxonil |

12 |

Phenylpyrrole |

Medallion (WDG, WP) |

Contact |

|

fluoxastrobin |

11 |

Strobilurin (QoI) |

Fame 480SC |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

flutolanil |

7 |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor |

ProStar 70WP, Moncut 70-DF |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

fluxapyroxad |

7 |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor |

Xzemplar |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

fosetyl-Al (Aluminum tris) |

33 |

Phosphonate |

Autograph, Chipco Aliette, Chipco Signature, Chipco Signature Xtra, Lesco Prodigy Signature, Viceroy 70DF |

Systemic Penetrant |

|

iprodione |

2 |

Dicarboximide |

Andersons Fungicide X, ArmorTech IP 233, Chipco 26 GT, Chipco 26019, Iprodione Pro, Lesco 18 Plus, Proturf Fungicide X, Raven |

Localized Penetrant |

|

isofetamid |

7 |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor |

Kabuto |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

mancozeb |

M3 |

Dithiocarbamate |

Dithane 75DF, Fore Rainshield 80WP, Junction, Lesco Mancozeb DG, Lesco 4 Flowable Mancozeb, Manzate Pro-Stick 200, Protect DF, WingMan (4L, DF) |

Contact |

|

mandestrobin |

11 |

Strobilurin (QoI) |

Pinpoint |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

maneb |

M3 |

Dithiocarbamate |

Maneb 80WP, Maneb 75DF, Pentathalon (LF, DF) |

Contact |

|

mefenoxam |

4 |

Phenylamide |

Andersons Pythium Control, Mefanoxam, Subdue MAXX |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

metalaxyl |

4 |

Phenylamide |

Subdue 2E, Subdue GR, Subdue WSP, Apron (seed treatment), Vireo MEC |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

metconazole |

3 |

Demethylation Inhibitor |

Tourney |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

myclobutanil |

3 |

Demethylation Inhibitor |

Andersons Golden Eagle, Eagle 20EW, Siskin |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

PCNB (pentachloronitrobenzene or quintozene) |

14 |

Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

Andersons FFII 15.4G, Defend 4F, Engage 75W, Fluid Fungicide II, Lesco Revere 4000 4F (10G), Parflo 4F, PCNB 12.5G, Penstar 75WP, Terraclor 400F (75WP), Turfcide 400F (10G) |

Contact |

|

penthiopyrad |

7 |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor |

Velista |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

phosphite (salts) |

33 |

Phosphonate |

Appear, Alude 5.2F, Biophos, Fiata Stessguard, Fosphite, Jetphiter, Magellan, Phostrol, Reliant, ReSyst 5F, Vital 4L |

Systemic Penetrant |

|

polyoxin D zinc salt |

19 |

Polyoxin |

Endorse 2.5WP, Affirm 11.3WDG |

Localized Penetrant |

|

propamocarb |

28 |

Carbamate |

Banol 6S |

Localized Penetrant |

|

propiconazole |

3 |

Demethylation Inhibitor |

ArmorTech PPZ 143, Banner GL, Banner MAXX II, Kestrel, Lesco Spectator, Procon-Z, ProPensity, Propiconazole Pro 1.3MEC, PropiMax, Strider |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

pyraclostrobin |

11 |

Strobilurin (QoI) |

Insignia Intrinsic SC, Insignia |

Localized Penetrant |

|

tebuconazole |

3 |

Demethylation Inhibitor |

Clearscape, Mirage Stressguard, Tebuconazole 3.6F, Torque, Skylark, |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

thiophanate-methyl |

1 |

Benzimidazole |

Allban, Andersons Systemic Fungicide 2.3G, ArmorTech TM 462, Cleary's 3336 (F, WP, DG lite, G, GC, Pro-Pak, Plus), Fungo (Flo, 50WSB), Lesco T-Storm 2G, Systec, T-Bird (4.5L, WDG), Tee-Off 4.5F, T-Methyl SPC 50 WSB, TM (4, SF, 85WDG) |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

thiram |

M3 |

Dithiocarbamate |

Defiant 75WDG, Thiram, Spotrete F |

Contact |

|

triadimefon |

3 |

Demethylation Inhibitor |

Accost 1G, Bayleton (50WSP, Flo), Andersons Fungicide VII 0.59G, Andersons 1% Bayleton 1G, Lebanon Bayleton 1G |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

trifloxystrobin |

11 |

Strobilurin (QoI) |

Compass 50WDG |

Localized Penetrant |

|

triticonazole 5 |

3 |

Demethylation Inhibitor |

Trinity, Chipco Triton (70WDG, Flo) |

Acropetal Penetrant |

|

vinclozolin |

2 |

Dicarboximide |

Curalan 4F, Touché EG |

Localized Penetrant |

|

1 Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) Code: fungicides with the same FRAC code have the same mode of action. M-codes indicate multi-site chemicals with low risk of resistance development. It is recommended to rotate applications by FRAC code and not to make sequential applications of fungicides with the same FRAC code.

|

||||

| Updated October 2017 | ||||

Table 21. Pre-mixed fungicide products registered for use on turf.

| Pre-mixed Products (Common Name) | FRAC 1 | Trade Name(s) |

|---|---|---|

|

azoxystrobin + chlorothalonil 2 |

11 + M5 |

Renown |

|

azoxystrobin + difenconazole |

11 + 3 |

Briskway |

|

azoxystrobin + propiconazole |

11 + 3 |

Headway, Headway G, Contend B |

|

Benzovindulflupyr + difenconazole |

3 + 7 |

Contend A |

|

chlorothalonil 2 + acibenzolar-S-methyl |

M5 + P1 |

Daconil Action |

|

chlorothalonil 2 + propiconazole |

M5 + 3 |

Concert II, Echo Propiconazole Turf Fungicide |

|

chlorothalonil 2 + tebuconazole |

M5 + 3 |

E-Scape ETQ |

|

chlorothalonil 2+ thiophanate-methyl |

M5 + 1 |

Broadside, ConSyst, Peregrine, TM/C WDG, Spectro |

|

chlorothalonil 2 + fludioxonil + propiconazole |

M5 + 12 + 3 |

Instrata |

|

chlorothalonil 2 + iprodione + tebuconazole + thiophanate-methyl |

M5 + 3 + 3 + 1 |

Enclave |

|

fluoxastrobin + chlorothalonil 2 |

11 + M5 |

Fame C |

|

fluoxastrobin + tebuconazole |

11 + 3 |

Fame T |

|

fluopyram + trifloxystrobin |

7 +11 |

Exteris |

|

iprodione + trifloxystrobin |

2 + 11 |

Interface Stressguard |

|

mancozeb + copper hydroxide |

M3 + M1 |

Junction |

|

mancozeb + myclobutanil |

M3 + 3 |

MANhandle |

|

propamocarb + fluopicolide |

28 + 43 |

Stellar |

|

pyraclostrobin + boscalid |

11 + 7 |

Honor |

|

pyraclostrobin + fluxapyroxad |

11 + 7 |

Lexicon |

|

pyraclostrobin + triticonazole 3 |

11 + 3 |

Pillar G Intrinsic |

|

thiophanate-methyl + chloroneb |

1 + 14 |

Proturf Fungicide IX |

|

thiophanate-methyl + flutolanil |

1 + 7 |

SysStar |

|

thiophanate-methyl + iprodione |

1 + 2 |

ArmorTech TMI 20/20, 26/36 Fungicide, Dovetail, Lesco Twosome, Proturf Fluid Fungicide |

|

thiophanate-methyl + mancozeb |

1 + M3 |

Duosan (WP, WSB) |

|

triadimefon + flutolanil |

3 + 7 |

Prostar Plus |

|

triadimefon + trifloxystrobin |

3 + 11 |

Armada |

|

triadimefon + trifloxystrobin + stress guard |

3 + 11 |

Tartan Stressguard |

|

1 Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) Code: fungicides with the same FRAC code have the same mode of action. M-codes indicate multi-site chemicals with low risk of resistance development. It is recommended to rotate applications by FRAC code and not to make sequential applications of fungicides with the same FRAC code. 2 Use of chlorothalonil is regulated in Massachusetts under the Public Drinking Water Supply protection regulation, see the Pesticide Regulations section of this guide for details. 3 Use of triticonazole is regulated in Massachusetts under the Public Drinking Water Supply protection regulations, see the Pesticide Regulations section of this guide for details. |

||

| Updated October 2017 | ||

Disease management with fungicides

To get the most from a fungicide application within an IPM program, it is important to proceed in an informed and intelligent manner. Keep in mind that fungal pathogens of plants are dependent on a susceptible host and specific, favorable environmental conditions in order to cause disease. Planting resistant turfgrass cultivars (see Turfgrass Selection: Species and Cultivars) and modifying the growing environment to help reduce disease will make fungicides more effective. The most important aspect of disease control is correct identification of your target pest. It is imperative to be certain of the identity of the pathogen prior to any fungicide application. If in doubt, send a turf sample to the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab (ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory). Knowing the pathogen allows you to know which grass species are susceptible or resistant, the optimum conditions for disease development, and the sensitivity of the pathogen to specific fungicides.

If you experience reduced efficacy or complete failure from fungicide applications to control dollar spot and athracnose, the UMass Pathology Lab offers both in vitro and molecular assays to assess potential fungicide resistance in the disease population. See the Fungicide Resistance Assay page of this web site for information.

![]() Table 22. Commonly used turf fungicides and the diseases they are labeled to control or suppress.

Table 22. Commonly used turf fungicides and the diseases they are labeled to control or suppress.