Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Lawn and Landscape Turf

version 1.51

This manual has been prepared by:

- Mary C. Owen, Extension Turf Specialist

- Jason D. Lanier, Extension Educator

Select technical content contributed by:

- Natalia Clifton - Extension Pesticide Specialist

- M. Bess Dicklow - Extension Plant Pathologist

- Dr. Scott Ebdon - Turf Agronomist

- Dr. Geunhwa Jung - Turf Pathologist

- Jason Lanier - Extension Educator

- Mary Owen - Extension Turf Specialist

- Randall Prostak - Extension Weed Specialist

- Dr. John Spargo - Soil Scientist

- Dr. Patricia Vittum - Turf Entomologist

and

additional sources as designated in the text.

Project assistance graciously provided by:

- Steve Anagnos - Lawn Care Pros, Martha’s Vineyard, MA

- Taryn LaScola - Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, Boston, MA

- Don McMahon - John Deere Landscapes, South Dennis, MA

- Carl Quist - Town of Longmeadow, MA

- Ted Wales - Hartney Greymont, Needham, MA

- Laurie Cadorette, UMass Extension

This project was originally part of a legislatively funded initiative undertaken by the University of Massachusetts Extension Turf Program in cooperation with the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources and the Massachusetts Farm Bureau Federation.

Best Management Practices - Overview

Please utilize the navigation menu to access the complete document

Overview

UMass Extension has recently developed a comprehensive manual of Best Management Practices (BMPs) for lawn and landscape turf, which is available for download by clicking the link to the right. The guide is a detailed collection of economically feasible methods that conserve water and other natural resources, protect environmental quality and contribute to sustainability.

The BMPs detailed in this document are agronomically sound, environmentally sensible strategies and techniques designed with the following objectives:

- to protect the environment

- to use resources in the most efficient manner possible

- to protect human health

- to enhance the positive benefits of turf in varied landscapes and uses

- to produce a functional turf

- to protect the value of properties

- to enhance the economic viability of businesses and communities

Lawn & Landscape Turf: A Key Resource

Residential and commercial lawns and utility-type turf comprise a significant portion of the the landscape in Massachusetts and beyond. These lawns may be at private residences, at business establishments, in industrial developments, on municipal properties, in parks, on public or private school grounds, and along roadsides and other utility areas. Lawns and similar turf areas are key resources, as they contribute to open space, provide recreation, add value to properties, and help to protect the environment. Properly maintained turf provides many functional, recreational, and ornamental benefits, which are summarized below.

Benefits of turf:

| Functional | Recreational | Ornamental | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Adapted from J. B. Beard and R. L. Green, 1994, from The Journal of Environmental Quality, The Role of Turfgrasses in Environmental Protection and Their Benefits to Humans. | |||

BMPs for Lawn & Landscape Turf

This BMP guide is intended for use in the management of lawn and landscape turf. While many of the practices delineated can be applied to the management of sports turf and other more intensively used turf, it is not the intent of this document to provide the more specialized BMPs that such intensive management systems require.

These BMPs are designed to be used in a wide range of lawn and landscape management situations. Not every BMP will apply to every site. Activities and practices may vary depending on management objectives and site parameters. In addition, there may be a specific practice or practices appropriate for an unusual site that does not appear in this

document.

When instituting a management program based on BMPs, the turf manager must first determine the desired functional quality of the lawn and the management level and resources necessary to achieve it. Various factors will need to be considered including site parameters, level and intent of use, potential for pest infestation, pest action level, and environmental sensitivity of the site.

BMPs for maintenance of lawn and landscape turf areas are most effectively implemented by an educated and experienced turf manager, but can also serve as guidelines for less experienced turf managers and others caring for lawn and landscape turf.

Integrated Pest Management

The BMPs in this document are based on the scientific principles and practices of integrated pest management (IPM). IPM is a systems approach that should form the foundation of any type of sound turf management program. This holds true whether the materials being used are organic, organic-based or synthetic. The components of IPM for lawn and landscape turf are detailed below and are described in more detail in pertinent sections of the document.

What is IPM? - Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a systematic approach to problem solving and decision making in turf management. In practicing IPM, the turf manager utilizes information about turf, pests, and environmental conditions in combination with proper cultural practices. Pest populations and possible impacts are monitored in accordance with a pre-determined management plan. Should monitoring indicate that action is justified, appropriate pest control measures are taken to prevent or control unacceptable turf damage. A sound IPM program has the potential to reduce reliance on pesticides because applications are made only when all other options to maintain the quality and integrity of the turf have been exhausted.

The key components of an IPM system for turf can be tailored to fit most management situations. The steps in developing a complete IPM program are as follows:

- Assess site conditions and history

- Determine client or customer expectations

- Determine pest action levels

- Establish a monitoring (scouting) program

- Identify the pest/problem

- Implement a management decision

- Keep accurate records and evaluate program

- Communicate

Introduction

LAWN AND LANDSCAPE TURF: A KEY RESOURCE

Residential and commercial lawns and utility-type turf comprise a significant portion of the Massachusetts landscape. These lawns may be at private residences, at business establishments, in industrial developments, on municipal properties, in parks, on public or private school grounds, and along roadsides and other utility areas. Lawns and similar turf areas are key resources, as they contribute to open space, provide recreation, add value to properties, and help to protect the environment.

Properly maintained turf provides many functional, recreational, and ornamental benefits, which are summarized below.

|

Functional |

Recreational |

Ornamental |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dust and mud control Entrapment of pollutants Environmental protection Fire prevention Glare reduction Ground water recharge Slope stabilization Heat abatement Noise abatement Security-visibility Soil loss and erosion control Protection of underground utility services Greenhouse gas reduction Storm water abatement |

Safe playing surfaces Low cost surfaces Mental health Physical health Entertainment |

Beauty Increased property value Community pride Complements the landscape Mental health |

|

Adapted from J. B. Beard and R. L. Green, 1994, from The Journal of Environmental Quality, The Role of Turfgrasses in Environmental Protection and Their Benefits to Humans.

Improperly or poorly maintained lawns are less functional in terms of aesthetics and recreation, may result in inefficient use of valuable natural resources such as water, and are more likely to be sources of environmental contamination.

Best Management Practices (BMPs) are intended to maximize the benefits of lawn areas and to minimize the potential for environmental impact that can happen as a result of inefficient, incorrect or irresponsible management practices.

BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES: AN OVERVIEW

Best Management Practices (BMPs) for lawn and landscape turf are economically feasible methods that conserve water and other natural resources, protect environmental quality and contribute to sustainability.

The BMPs detailed in this document are agronomically sound, environmentally sensible strategies and techniques designed with the following objectives:

- to protect the environment

- to use resources in the most efficient manner possible

- to protect human health

- to enhance the positive benefits of turf in varied landscapes and uses

- to produce a functional turf

- to protect the value of properties

- to enhance the economic viability of Massachusetts businesses and communities

The BMPs in this document are based on the scientific principles and practices of integrated pest management (IPM). IPM is a systems approach that should form the foundation of any type of sound turf management program. This holds true whether the materials being used are organic, organic-based or synthetic. The components of IPM for lawn and landscape turf are detailed below and are described in more detail in later pertinent sections of this document.

What is IPM? - Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a systematic approach to problem solving and decision making in turf management. In practicing IPM, the turf manager utilizes information about turf, pests, and environmental conditions in combination with proper cultural practices. Pest populations and possible impacts are monitored in accordance with a pre-determined management plan. Should monitoring indicate that action is justified, appropriate pest control measures are taken to prevent or control unacceptable turf damage. A sound IPM program has the potential to reduce reliance on pesticides because applications are made only when all other options to maintain the quality and integrity of the turf have been exhausted.

The key components of an IPM system for turf can be tailored to fit most management situations. The steps in developing a complete IPM program are as follows:

-

Assess site conditions and history

-

Determine client or customer expectations

-

Determine pest action levels

-

Establish a monitoring (scouting) program

-

Identify the pest/problem

-

Implement a management decision

-

Keep accurate records and evaluate program

-

Communicate

These BMPs are intended for use in the management of lawn and landscape turf. While many of the practices delineated can be applied to the management of sports turf and other more intensively used turf, it is not the intent of this document to provide the more specialized BMPs that such intensive management systems require.

These BMPs are designed to be used in a wide range of lawn and landscape management situations. Not every BMP will apply to every site. Activities and practices may vary depending on management objectives and site parameters. In addition, there may be a specific practice or practices appropriate for an unusual site that does not appear in this document.

When instituting a management program based on BMPs, the turf manager must first determine the desired functional quality of the lawn and the management level and resources necessary to achieve it. Various factors will need to be considered including site parameters, level and intent of use, potential for pest infestation, pest action level, and environmental sensitivity of the site.

BMPs for maintenance of lawn and landscape turf areas are most effectively implemented by an educated and experienced turf manager, but can also serve as guidelines for less experienced turf managers and others caring for lawn and landscape turf.

USING THIS DOCUMENT

The following describes the manner in which this document is set up:

OBJECTIVE

Each section of this document contains management objectives that lead to overall goals: safety, protection of water and other natural resources; enhancement of environmental quality, sustainability, and economic feasibility.

Following each objective are the BMPs that support and contribute to that particular objective.

- Additional supporting information and detail appears in the bulleted text below each BMP.

1. Development and Maintenance of a Knowledge Base

OBJECTIVE

Maintain organized references on agronomics, management materials and pests, and provide for easy access to information as needed.

Develop and maintain professional turf management competency.

- This may include attending degree or certificate programs, workshops, conferences, field days, seminars and/or webinars, and in-house and on-the-job training

Learn about pest identification and biology to effectively implement pest management strategies.

- If an insect, disease, or weed population affects a lawn area, the turf manager must be knowledgeable about the life cycle of the problem pest.

- For example, when is damage most likely to occur? What is the most susceptible stage for control? How can cultural practices be targeted to reduce pest populations?

Maintain an organized library of turf management reference materials.

- The development of a library of reference materials will provide easy access to information as needed.

- Many excellent references are available. Consult Appendix E on page 127 of this document for a list of suggested resources and references.

Reference materials and other reliable information sources could include:

-

reference textbooks (see appendix)

-

trade journals

-

pest management guides

-

university and associated newsletters and e-newsletters

-

electronic media, websites

Create and maintain current files for key pests (weeds, diseases, and insects) as well as abiotic stresses.

- Hard copy or electronic files may consist of articles, fact sheets, images, web sites, excerpts from larger publications, personal notes, etc.

Example information that might be included in each pest file:

- life cycle

- environmental conditions and weather that favor pest activity

- symptoms

- best monitoring time

- best monitoring technique

- effective management tools and techniques: cultural, chemical, biological

Obtain and maintain appropriate licenses and professional certifications.

- Individuals applying pesticides should be properly licensed and/or certified as required by law.

- Association memberships and professional certification programs (e.g. MCLP, MCH, CSFM) are useful avenues for professional development.

Identify and access a reliable source of weather information regularly.

- Weather conditions and soil temperatures play a role in determining timing of cultural practices as well as pest activity and severity.

Types of critical data should include current, accurately predicted and archived information on:

- most recent and forecast weather

- temperature

- precipitation

- relative humidity and dew points

Note and record specific weather or phenological information.

- It is often useful to monitor and record soil temperatures at 1.0 inch weekly during key times of the season at locations representative of the range of different microclimates being managed.

- A record of dates of full bloom of key bio-indicator plants (i.e. Forsythia, dogwood, horsechestnut) can be important in tracking pest development.

- Major, extreme or unusual weather events and their effects on turf or implications for applications of fertilizer or pest management materials.

2. Site Assessment

OBJECTIVE: Determine and record site conditions, including areas of environmental sensitivity, as well as current and past problems and potential for future problems.

Conduct a detailed assessment of each site to be managed.

- Accurate site specifications are indispensible for planning with relation to management practices, materials applications, and renovation or reconstruction.

- Problem areas that impact turf health directly affect the potential loss of turf quality and function and increase the likelihood of pest infestations.

Points to consider in a thorough site assessment include:

- map or photo record of property

- square footage of turf area(s) being managed

- drainage patterns

- as-built drawings/maps of drainage and irrigation systems

- determination of functional condition and adequacy of drainage and irrigation systems

- the age, condition, and species composition of the turf (including cultivars if known)

- the physical condition, texture, and variation of soils on the site

- a current soil pH and nutrient analysis

- the fertility history and a summary of the current fertility program

- a pest history and current or potential problems

Identify and record permanent features of each site in relation to management of the turf.

- Permanent features on or in close proximity to the site should be assessed from two perspectives:

- How turf function and quality might be impacted by these features.

- How these features might be impacted by turf management practices.

The following are important items and structures that might be included:

- trees, shrubs, gardens and other landscape plantings.

- driveways and walkways

- parking lots and roadways

- fencing

- buildings

- temporary structures

- monuments or grave markers

- playgrounds and/or daycare facilities

- decorative ponds

- significant abutters that have potential for impact

- Changes to this record should be made as they occur.

Devote particular attention to the identification of areas of environmental sensitivity.

- Similar to above, areas of environmental sensitivity on or in close proximity to the site should be assessed from two perspectives:

- How turf function and quality might be impacted by these areas.

- How these areas might be impacted by turf management practices.

The following are key areas that should be included:

- wetland protection resource areas

- wells on property

- wells in proximity to property

- Zone I & II areas

- surface water features

- high water table areas

- catch basins

- exposed bedrock

- other environmentally sensitive areas

Determine and record agronomic problems in key locations and consider potential solutions.

- The recognition of agronomic problems is the first step in developing a solution.

Problems to note include but are not limited to the following:

- poorly adapted turfgrass species or cultivars

- insufficient fertility

- undesirable soil types

- excessive thatch

- excessive traffic stress

- compaction

- pet damage

- poor drainage

- shade

- localized dry spots

- poor air circulation

- southwest facing slopes

- tree root influence

- shallow soil or bedrock

- areas prone to damage from snow removal or salt application

3. Development of a Management Plan

OBJECTIVE: Determine the intended use and expected level of turf performance in making strategic and cultural management decisions.

Determine customer or client expectations to inform management objectives.

- In general, the higher the level of quality desired, and the more intense the use of the turf, the higher the level of management needed to maintain a quality surface.

- Set realistic expectations based on communication between turf practitioner and customer or client.

Expectations considerations include, but may not be limited to:

- use and appearance of the turf

- acceptable level of pest infestation

- acceptable level of abiotic stress

- use of water and other resources

- use of synthetic, organic-based, or organic management materials

- budget and other financial resources

- other site specific details

OBJECTIVE: Determine and document action levels for various pests.

How much pest activity can be tolerated before action is necessary?

- This question will help to determine the response threshold or action level.

- The action level is the point at which a pest population reaches a level capable of causing unacceptable damage to the turf.

- The higher the level of turf performance desired, the lower the action level and the more likely it is that a turf manager will need to make a pesticide application to manage a problem pest.

Establish action levels for each key pest according to turf management objectives.

- Action levels for various pests will vary from site to site and may even vary from area to area on a given site.

- Due to the many factors that play a role in determining action levels, setting "across the board" levels is often not useful.

- Action levels may change during the growing season, in response to changes in management inputs, or in response to other pest or abiotic problems.

- Action levels may be affected by the number of monitoring events or visits. In many cases, the less often monitoring is done, the more likely it is that the action level will be lower.

- Ancillary information such as plant phenology and bio-indicators (stage and date of plant development) as well as growing degree days can also be considered.

The following factors will influence action levels and should be considered carefully:

- client or customer expectations

- management objectives

- turfgrass species and cultivars present

- turf use

- vigor and condition of turf

- time of year

- weather and environmental conditions

OBJECTIVE: Develop and implement a site specific management plan.

Set strategies for the upcoming year with an annual management plan.

- Formulate a yearly management plan based on site assessment information, client expectations and pest action levels as determined for the site.

The following information at a minimum should be included:

-

management objectives and practices

-

regulations that impact the particular site, and compliance factors for those regulations

-

identification of agronomic problems, with a plan for addressing causes:

- irrigation

- drainage

- excess wear and traffic

- landscaping (trees and shrubs)

- soil problems

-

cultural practices:

- construction, renovation, repair if needed

- seeding/overseeding

- irrigation

- fertility management

- mowing

- aeration and topdressing

- other practices specific to the site

-

scouting timetable and procedures

- identification of key pests in key locations at key times

- training and assignment of scouting personnel

-

pest management strategies

- determination of pest action levels

- scouting/monitoring plan

- cultural management

- biological management

- pesticide management

Monitor or scout for pests, potential pest problems and environmental stresses.

- Managed sites should be checked on a routine basis for pest presence, pest population density, and pest damage.

- Other potential problems (i.e. heat stress, excessive thatch accumulation, etc) should also be noted and recorded.

- Consult the appropriate pest sections of this manual for information useful in monitoring disease, insect, and weed pests as well as problems caused by abiotic factors.

- Refer to the Turf Pest Damage Monitoring Chart for approximations of when damage is most likely to occur.

Keep a written record of monitoring findings with an intended course of action.

- List or map locations where particular or key pests or problems first occurred during critical periods.

- List or map locations where particular environmental or other abiotic stresses first occurred during critical periods.

- Record action needed, and also action taken.

Record management activities.

- Keep a detailed record of yearly growing conditions and management activities.

Suggested record items:

- temperature

- precipitation

- humidity

- pest problems

- pest ‘hot spots’

- pesticide applications and results

- timing, frequency and effectiveness of cultural practices

- fertilizer and other materials applications

- soil and tissue test results

- soil pH

- uncommon occurrences such as flood, prolonged ice cover, etc.

- Note management activities that differ from those outlined in the yearly management plan.

- Determine if measures taken to manage a pest or alleviate a problem were truly effective in protecting and maintaining the quality and viability of the turf. These evaluations should be maintained as a key aspect of the written record.

- Keep pesticide application records as required by law.

- If applicable, customer program, invoicing and associated records should be kept on file.

- Staff are should be trained in Right to Know and other pertinent laws, and documentation should be retained in personnel files.

- Training records for staff using or handling materials and doing field work should be retained.

Encourage and maintain communication between supervisors, crew and other staff.

- Effective communication will promote success of management decisions and results.

- Train staff and crew in proper procedures.

Share the yearly management plan.

- Share management plans with appropriate staff, clients, and/or end-users. Discuss as needed.

- Clients, and/or end-users who utilize turf subject to pesticide applications should receive notification and documentation as required by law.

- If requested by clients and/or end-users, provide advance notice of site visits and applications.

- Provide an information sheet, post-treatment instructions and documentation to clients and/or end-users as appropriate.

Evaluate the management plan as implemented.

- All aspects of the management plan including pest management strategies should be evaluated each year and a written summary kept.

- Management strategies that need to be adjusted or implemented for future seasons can be identified in the course of the annual evaluation.

4. Turfgrass Selection

OBJECTIVE: Select turfgrass species and cultivars that are well adapted to the environmental conditions and to the intended use and maintenance level of a particular site.

For additional, detailed Turfgrass Selection information, including varieties that have performed well in Massachusetts in NTEP trials, see the Turfgrass Selection: Species & Varieties chapter of UMass Extension's Professional Guide for IPM in Turf.

Know the strengths and weaknesses of potential species and cultivars and select the right grasses for your site and management program.

- Turfgrass species vary in terms of appearance, appropriate uses, cultural requirements, pest resistance and stress tolerance. Individual cultivars (or varieties) within species provide additional options for effectively matching grasses with growing conditions and desired performance.

- Selection of adapted turfgrass species and cultivars is fundamental to the success of any management program for turf, as poorly adapted species and cultivars are major causes of turf deterioration.

- Well-adapted grasses require fewer inputs in terms of water, fertilizer, and pesticides, and are far more likely to perform as intended and exhibit favorable characteristics.

Carefully consider the desired level of cultural intensity.

- Consider the intended level of cultural intensity, the type of use, and the desired degree of turf performance.

- Some grasses require a higher level of management attention (water, fertility, mowing) to perform adequately, relative to other grasses.

- Higher maintenance species are best used where management receives a greater level of attention and effort, and is resourced accordingly. Common high maintenance areas include golf courses, athletic fields, parks, and some commercial or residential lawns.

- If a lower-input management scheme is desired, grasses are available that perform at an acceptable level with a relatively smaller degree of maintenance.

- Low maintenance turf species are typically adapted to situations with reduced inputs such as mowing, fertility, and irrigation. Areas appropriate for low maintenance species include roadsides, parking lots, industrial complexes, and some commercial or residential lawns.

- When specifying mixed stands, consider how they may trend if inputs are higher or lower.

Identify potential growth-limiting factors.

- Determine the characteristics and the adaptations of the turfgrass species (growth habit, recuperative potential, leaf texture, shoot density, establishment rate, appropriate mowing height, etc).

- Abiotic growth limiting (stress) factors include conditions such as shade, traffic, infertility, acidic soil pH, flooding, shallow root zone, poor soil condition, low temperature, drought, close mowing, etc.

- Biotic growth limiting factors include pests such as insects, diseases and weeds.

|

Species |

Wear |

Compaction |

Recovery |

Soil Texture |

Soil pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kentucky bluegrass |

Fair |

Good |

Good |

Well drained |

6.0 to 7.0 |

|

Perennial ryegrass |

Excellent |

Excellent |

Poor |

Variable |

6.0 to 7.0 |

|

Fine Fescues (Chewings, creeping red, hard) |

Poor |

Poor |

Fair |

Well drained |

5.5 to 6.5 |

|

Tall fescue |

Excellent |

Fair |

Poor |

Variable |

5.5 to 6.5 |

|

Species |

Cold |

Heat |

Drought |

Salinity |

Submersion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kentucky bluegrass |

Excellent |

Fair |

Good |

Poor |

Fair |

|

Perennial ryegrass |

Fair |

Fair |

Good |

Fair |

Fair |

|

Fine fescues (Chewings, creeping red, hard) |

Good |

Fair |

Good |

Poor |

Poor |

|

Tall fescue |

Fair |

Good |

Excellent |

Good |

Good |

|

Species |

Shade |

Fertility * |

Height of Cut |

Mowing Frequency |

Thatch Tendency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kentucky Bluegrass |

Poor |

Medium-High |

1.5 to 3.5 inch |

Low-Medium |

Medium |

|

Perennial Ryegrass |

Poor |

Medium-High |

1.5 to 3.5 inch |

High |

Low |

|

Fine fescues (Chewings, creeping red, hard) |

Excellent |

Low |

1.5 to 3.5 inch |

Low |

Medium |

|

Tall Fescue |

Fair |

Medium-High |

1.5 to 3.5 inch |

Medium |

Low |

* Fertility levels, in lbs. N per 1000 sq. ft.: medium-high = 3 to 5; low = 1 to 2.

Take advantage of National Turfgrass Evaluation Program (NTEP) data.

- NTEP provides extensive, reliable information about the performance of turfgrass species and cultivars in specific regions of the country.

- NTEP does not make recommendations; therefore the data must be interpreted and used to make informed choices.

- The key parameter provided by NTEP is turfgrass quality (TQ). Other available descriptive data may include genetic color, density, leaf texture, winter injury, traffic tolerance, disease potential, etc.

- NTEP information is free and can be accessed on the web at http://www.ntep.org.

Mix and/or blend species and cultivars whenever possible.

- Use of a single turfgrass species for establishment of a stand is rarely appropriate for lawns and similar turf areas, and is more common on some athletic fields and many golf courses.

- A turfgrass seed mix contains two or more different species of grasses.

- A turfgrass seed blend contains two or more cultivars of the same species of grass.

- Where appropriate, informed mixing and blending often results in a well-rounded turf that performs better than the sum of its parts.

- To incorporate diverse tolerances to pest and environmental stresses, mixes and/or blends are nearly always preferred to ‘monostands’ (a planting consisting of the same species and/or cultivar).

|

Use |

Species (% by weight) |

Rate (lbs/1000 ft2) |

|---|---|---|

|

Lawns: sun, med. to high maintenance |

65 to 75% Kentucky bluegrass* 10 to 20% perennial ryegrass* 15% fine fescue** |

3 to 4 |

|

Lawns: sun, low maintenance |

65% fine fescue* 10-20% perennial ryegrass* remainder Kentucky bluegrass |

4 to 6 |

|

Lawns: shade |

80 to 90% fine fescue* 10 to 20% perennial ryegrass* |

4 to 6 |

|

Lawns:well drained |

80% shade tolerant K. bluegrass* 20% perennial ryegrass* |

3 to 4 |

|

*Two to three improved cultivars recommended. ** One or more improved cultivars recommended. |

|

|

Exercise special care when selecting and managing tall fescue.

- Tall fescue is more readily adaptable to certain areas of New England, particularly the southern coastal areas.

- Some tall fescue cultivars can become coarse and unthrifty under conditions in which better adapted turfgrasses may perform better.

- Careful cultivar selection is critical, not only for performance and quality, but also for disease tolerance.

- Tall fescue is particularly susceptible to brown patch and Pythium diseases. Consult UMass Extension’s Professional Guide for IPM in Turf in Massachusetts, or NTEP data for disease tolerance of specific cultivars.

- Many tall fescue cultivars tend to become clumpy in heavily trafficked areas, and may require frequent overseeding to maintain acceptable density.

- When it is desirable to use tall fescue in a lawn or in the landscape, use a mix of tall fescue in combination with Kentucky bluegrass or perennial ryegrass, with no less than 80% of the mix being tall fescue.

5. Establishment, Renovation & Repair

Turf establishment, by the simplest definition, is the planting of turfgrasses. There are several different types of planting events, ranging from new plantings (i.e. constructing a new turf area where one did not exist before), to renovation or re-construction of an existing turf area, to overseeding or repairs for established turf.

Mature, well-established turf not only the most functional, but also most tolerant of pests, use, cultural practices, and environmental stresses. Well-established turf is also more likely to exhibit a desirable appearance. The goal of most establishment projects, then, is to produce a turf stand that is dense, deeply rooted, and will provide rapid cover and develop to maturity as quickly as possible.

What separates planting and establishment is that planting is an act, but establishment is a process. Turf establishment includes not only the act of planting, but also encompasses the period of time between planting and the point at which the turf reaches a certain level of maturity and appearance. This is commonly referred to as the establishment period. Specialized attention and practices are required during this period to help ensure a successful planting project. The length of the establishment period can vary considerably depending on many factors including site conditions, weather conditions, time of year, and turfgrass species/cultivars used.

A solid plan for any establishment project is critical. After a thorough site assessment and following proper turfgrass selection principles to match appropriate turfgrass species and cultivars to site conditions, user expectations, and resources for management, turf establishment has three general phases:

- Phase 1 – Site Preparation: evaluation, soil testing, cultivation, grading, amendments, seedbed preparation

- Phase 2 – Planting: seeding, sodding

- Phase 3 – Establishment Period: post-planting care in terms of mulches, irrigation, mowing, and fertilizer.

OBJECTIVE: Seek to optimize establishment timing for the best chance of short- and long-term success.

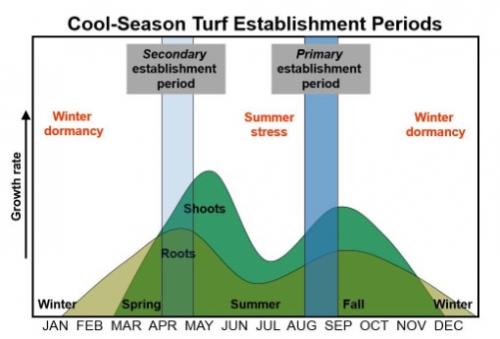

Plant during favorable periods whenever possible and avoid stress and pre-stress periods.

- Temperature is key to the adaptation of grasses (where they grow well), as well as when they grow well (month-to-month and season-to-season).

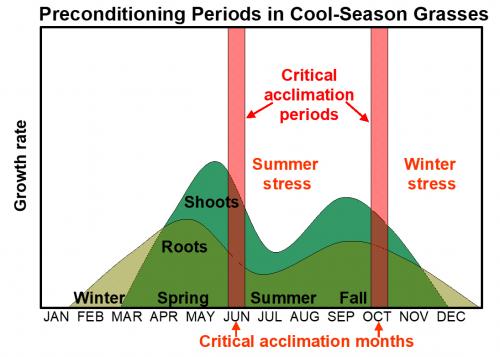

- Cool-season turfgrass shoots grow best when air temperatures are in the range of 60°-75° F, and cool-season turfgrass roots grow best when soil temperatures are in the range of 50°-65° F

- Seasonal peaks in growth (spring and late summer) correspond with periods when temperatures are in the favorable range, and growth slows or stops during periods when temperatures are outside of this range (above or below).

- The ideal approach, then, is to plant just ahead of the most favorable periods for growth, to align the establishment period with the best possible conditions.

- Whenever possible, avoid planting during stress and pre-stress periods (eg. late spring, summer, late fall). Planting during these periods greatly reduces the potential for long-term success, and often requires greater effort and inputs.

Recognize that late summer is vastly preferable to spring for planting of cool-season turfgrasses in New England.

- Although a period of favorable growing conditions occurs in both spring and late summer in New England, a host of additional factors make late summer the ideal planting time:

|

Factors |

Spring |

Late Summer |

|---|---|---|

|

Timing: * |

Best approach is to plant as early as possible, but opportunity varies based on winter/spring transition. |

Best planting window approximately 3rd week of August to 3rd week of September, on average. |

|

Growth period exposure: |

Only one brief favorable growth period before the first onset of summer stress. |

Two favorable periods before first onset of summer stress. |

|

Soil moisture: |

Typically wetter soils (more difficult to prepare). Less initial need for irrigation. |

Typically drier soils (easier to prepare). More need for irrigation, particularly during early establishment. |

|

Soil temperature: |

Cooler soil temperatures. |

Warmer soil temperatures. |

|

Precipitation and evaporative demand: |

Decreasing precipitation, on average, and increasing evaporation. |

Increasing precipitation, on average, and decreasing evaporation. |

|

Weed competition: |

Increasing competition from annual, warm-season weeds, in particular crabgrass (herbicides normally required for control). |

Little competition from germinating weeds (herbicides not typically necessary). Only winter annual weeds germinate in the fall. |

|

Herbicide conflicts: |

Seeding not compatible with applications of several common preemergence herbicides. |

Preemergence herbicides not commonly applied/necessary during this period. |

|

Cultivation: |

Cultivation required for planting can stir the soil seed bank during the period of maximum annual weed seed germination. |

Most appropriate time for annual cultivation practices, often performed in conjunction with planting. |

|

Deciduous trees: |

Deciduous trees leafing out = increasing shade. |

Deciduous trees soon to drop leaves = decreasing shade. Must account for leaf drop on tiny seedlings. |

*In Massachusetts, the best windows for establishment may vary on parts of Cape Cod and on the islands that warm later in the spring and stay warmer later into the fall.

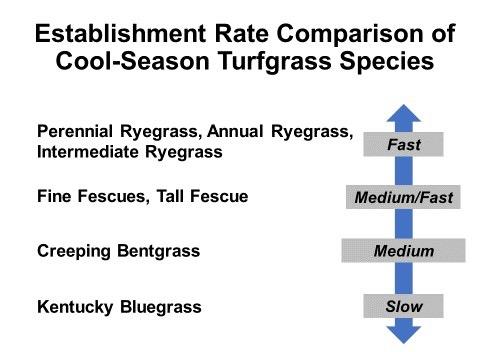

Account for the establishment rate of the turfgrass species and varieties used.

- The overall speed of turf establishment is affected by a number of factors including temperature, moisture, fertility, site conditions, etc.

- A key trait that influences the length of the establishment period is the inherent establishment rate of the turfgrass species and varieties used.

In general, an establishment rate comparison by cool-season turfgrass species is as follows:

- Thus, slower establishing species, such as Kentucky bluegrass, should be seeded earlier during appropriate planting "windows".

- Slower species will require a comparatively longer period of specialized care during the establishment phase.

- With faster species, such as perennial ryegrass, more timing flexibility is possible.

- Faster establishing species are also better suited to overseeding or repairs, when factors such as competition with existing grasses or a pressing need for rapid cover come into play.

Understand that expected returns begin to diminish rapidly as fall progresses.

- In fall, average temperatures gradually decrease. Colder nights have an especially pronounced effect.

- Both day length and the angle of the sun are decreasing (shorter days and lower levels of available light = less photosynthesis = less vigorous growth and development).

- At some point in the fall, plant processes begin to shift away from growth and towards preparation for winter. Thus, grasses planted later in the season will be slower to establish, less hardy, and more susceptible to winter injury.

What about dormant seeding?

- Dormant seeding is seeding after soil temperatures seasonally fall below the range in which seeds germinate (< 40°-45° F... dormant seeding should not be attempted until temperatures fall below this range), with the idea that the seeds will lie dormant over winter and begin to germinate as soon as conditions allow in the spring.

- When late-summer seeding is not an option, dormant seeding may or may not be as effective as an early spring seeding

- A gamble… cannot be counted on to work every time or as well as seeding at more desirable times! Best for enhancements, emergencies, and last resorts, as opposed to new projects.

- Follow-up seeding or overseeding may be needed in the following season in cases where conditions have not been favorable for a fully successful dormant seeding.

|

Dormant Seeding Pros |

Dormant Seeding Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Pay special attention to weeds for spring establishment projects.

- When turf must be planted in the spring, one of the most significant challenges is competition from increasing annual weed pressure. A number of these weed species have warm-season (C4) physiology, which enables them to thrive under hot and dry conditions.

- Since cool-season turfgrasses are increasingly stressed under such conditions, warm-season weeds become increasingly and overwhelmingly competitive as spring progresses into summer. The first step to combat this problem with a spring seeding is to plant as early as possible.

- For the best chance of success, spring seedings are often performed in conjunction with application of pre-emergence herbicides.

- Several common pre-emergence herbicides are not compatible with seeding, and vice versa, and many herbicides cannot be used post-emergence for a period of time as well. The few currently labeled herbicide materials that are compatible with seeding include mesotrione and quinclorac.

- For specific management approaches for spring weed control, refer to the Weed Management chapter of UMass Extension’s Professional Guide for IPM in Turf for Massachusetts.

OBJECTIVE: Properly prepare the planting site to promote rapid and complete establishment.

Have a sound project plan, starting with site preparation

- Use information collected during site assessment to make site modifications, if needed.

- Establishment projects should include proper soil preparation, which includes soil testing.

- Since turf is a perennial system, new establishment projects or re-construction projects that "open" the soil present a rare opportunity to fully incorporate lime, fertilizer, and other amendments into the root zone; to install sub-surface features such as drainage or irrigation components; and to alter the grade.

Test existing soil, as well as soil or amendments, which may be added to the site.

- Test for chemical characteristics (pH, fertility, nutrient reserves, heavy metals, salinity, etc.).

- Test for physical characteristics (texture, particle size distribution, percent organic matter etc.).

- Ensure that any amendment materials are compatible with the soil already present on the site. Uninformed additions of soil or organic material are strongly discouraged and may lead to soil problems that are extremely difficult to address.

- For comprehensive details on soil testing and soil fertility, refer to the Soil and Nutrient Management chapter of this document.

Conduct site preparation activities in a manner that minimizes adverse environmental impact and results in no future compromise to the turf system.

- Control all weeds, especially difficult perennial weeds.

- Remove all debris from land clearing and similar operations; never bury debris. Debris left to decay in the soil may result in future problems such as fairy rings, proliferation of mushrooms, poor drainage, depressions, stress spots or failures.

- Work to minimize the area of soil exposed as well as amount of time that soil is bare.

- Protect any exposed soil from erosion. Use temporary groundcovers or cover crops if land will be bare for an extended period. Cover stockpiled soil, and do not leave soil exposed over winter.

- Protect entryways to water resources (i.e. catch basins and other drainage pathways) from runoff from exposed and stockpiled soil or amendments. Environmental protection measures may include installation of erosion control barriers such as straw bales, silt fences, berms, compost filter socks and sediment basins. Maintain protection until turf is well established.

- When conducting sitework with heavy equipment, remove and stockpile topsoil and/or bring in new topsoil. Mix soil and amendments off-site to reduce compaction concerns.

Grade properly.

- Provide for proper water movement and drainage.

- Surface drainage: movement of water across the top of the soil, via directed slope.

- Internal drainage: downward movement of water into, through and out of the soil profile and drainage features.

- When grading, it is especially important to consider a range of scenarios, from regular precipitation to extreme storm events, to help ensure that water will move off the site in an effective and environmentally responsible manner under a variety of conditions.

- When rough grading, be sure to match contours of sub-grade to desired finished grade, to ensure adequate and consistent root zone depth.

- Install underground irrigation and drainage components beneath the sub-grade. Eliminate depressions and pitch the grade away from buildings.

- Avoid altering the grade around established trees to prevent damage to the root system (no cutting, no filling).

- Compaction caused by construction activities should be remedied before topsoil is replaced.

- Allow for soil to settle before final grading. Final grading should be done just prior to final bed preparation for seeding or sodding.

Provide for irrigation and sub-surface and surface drainage if necessary.

- Install any sub-surface irrigation components prior to planting if specified and appropriate for the site and the management program.

- Where surface drainage is not sufficient and where otherwise warranted, sub-surface drainage should be installed.

- Where possible, and when it will not interfere with the use of the turf, grade to allow turf to take advantage of runoff from impervious surfaces such as parking areas, driveways, and rooftops.

Prepare the root zone.

- An ideal root zone for a lawn is friable, fertile, and has good infiltration, drainage and water holding capacity.

- Provide for a minimum 6 inch depth of root zone.

- When using existing soil incorporate amendments, fertilizer and liming materials as specified by results of a soil test. Refer to the Soil and Nutrient Management chapter of this document for additional information.

- When amending existing soil, till in small amounts at a time to achieve uniform distribution.

- Note that excessive tilling or tilling when the soil is wet can damage soil structure.

- Whenever possible, and when amending with large quantities of materials, remove topsoil and mix with amendments off-site, then replace uniformly mixed/amended soil.

Prepare the final planting bed.

- The final objective is a firm (not compacted), granular bed for seed or sod.

- Remove all rocks and debris and ensure a uniform surface.

- Drag or hand rake the site if necessary.

- Irrigate lightly to settle the soil, or roll lightly to firm if needed.

OBJECTIVE: Use a planting method that is appropriate for the site, the budget, and project objectives.

SEEDING

Know that the single most important investment in ensuring high quality turf is the use of high quality seed.

- Seed cost is relatively low when compared with other turf management inputs.

- An investment in high quality seed is relatively small when the potential number of years that a turf stand can persist is considered, as well as the reduction in management inputs often realized with higher quality turf.

Read and understand turfgrass seed labels.

To inform and protect the buyer, certain information must be listed on the seed label:

- The name of the seller

- The lot number: can be used to track the origin of the seed. Useful as a reference if a problem develops.

- The seed variety or varieties: in some cases it is legal to list species with only VNS (Variety Not Stated) designation.

- Pure seed content (purity): % by weight of each species or variety. A measure of seed quantity, not quality.

- Germination percentage: % of each pure seed component that was capable of growth at the time of testing (under ideal conditions).

- Date: the date on which the seed was tested. Germination percentage declines with age of the seed.

- Crop seed content: Can be more undesirable than weed seeds as a source of contamination. Should be as low as possible!

- Weed seed content: % of all seeds that are not pure seed or crop seed. Ideally 0.5% or less.

- Noxious weeds: expressed as per pound or per ounce of content weeds officially classified as difficult to manage.

- Inert matter: % by weight of all material in the seed that will not grow. Lower inert matter = better value!

For more information, refer to our Understanding a Turfgrass Seed Label fact sheet.

Use certified seed whenever possible and available.

- Certified seed must meet minimums for purity and more rigid standards for weed and crop seed content.

- Seed certification helps to guarantee authenticity of turfgrass varieties.

- Certified seed carries a color-coded certification tag: blue tag = 95% purity, gold tag = 96-97% purity.

Determine and use an appropriate seeding rate.

-

Proper seeding rate is critical to achieving a functional turfgrass stand that will develop to maturity as quickly as possible.

-

Turfgrass plants compete for space and resources with each other and with potential invaders (weeds).

Lower than optimum seeding rate =

Higher than optimum seeding rate* =

An open stand of low shoot density which is less functional and encourages weed invasion.

A stand composed of many small plants that are slow to mature and less tolerant of stress.

* Please note that high rate overseeding and repairs, when done properly, is an accepted and successful practice in many sports fields management programs.

- Optimum seeding rate ranges take into account factors such as: seed size and number per pound, growth habit, minimum purity and germination differences among species.

- Large seeds = less seed per pound = higher seeding rate

- Small seeds = more seed per pound = lower seeding rate

- Growth habit affects seeding rate: adhering to at least minimum seeding rates is especially important with bunch-type grasses, which have a lower capacity to spread laterally relative to stoloniferous or rhizomatous grasses.

- The better the conditions for seeding (soil type, seedbed, time of year) the less seed will be needed.

- As a general rule, seeding rates should be increased by up to 50% to compensate for poor conditions.

Factors or conditions that contribute to poor germination and seedling survival include:

- poor soil conditions, including drainage (excessive or poor), improper pH, nutrient deficiency, compaction, salinity.

- poor seedbed because of inadequate or excessive soil firming, excessive tilling, rocks and debris at soil surface, poor seed to soil contact or coverage, inadequate or excessive mulch, or steep grades that contribute to soil erosion.

- less than optimum seeding time, causing late spring/early summer mortality (drought and heat stress, weed competition, and disease) or late fall/early winter mortality (winter desiccation, frost heaves, unfavorable temperature).

- poor post planting care, consisting of inadequate soil moisture (irrigation), improper mowing and fertilization practices, not controlling traffic, etc.

For specific seeding rate guidelines for turfgrass species and recommended mixtures, refer to the Turfgrass Selection: Species and Varieties chapter of UMass Extension’s Professional Guide for IPM in Turf for Massachusetts.

Use an appropriate and effective seeding method.

- Maximize seed to soil contact through every avenue available.

- Divide seed in half and seed in two directions when possible for maximum coverage and uniformity, using equipment appropriate to the particular site and operation.

- Drop spreaders are somewhat preferred for precise application (better suited for tight areas and around non-turf areas), rotary spreaders are less precise (better suited for larger, open areas).

- Spreader calibration is seldom practical for seed. A general guideline is to start at 20% open/80% closed and adjust as needed (seed is much more forgiving than fertilizers or pesticides).

- Seed ‘drills’ (Brillion-type seeders) are very precise, but best suited for large areas and sod farms

- Seeding by hand is imprecise and should be avoided with the exception of small repairs.

Consider the use of hydroseeding on large or hard to access areas.

- Careful attention to turfgrass selection, proper use of quality mulch materials, correct application methods, and good follow-up care lead to better long-term results from hydroseeding. For example, contrary to popular belief, the use of hydroseeding does not typically eliminate the need for careful irrigation during the establishment period.

|

Hydroseeding Pros |

Hydroseeding Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

SODDING

Consider establishment from sod if the site, project and budget allow.

- Sodding involves transplanting of turf from one site to another.

- Fast and effective, but expensive compared to other establishment methods.

- Can provide opportunities for establishment at times that would otherwise be less than ideal. Sod laid in spring, for example, is better able to compete with annual weed pressure than turf planted from seed.

- Most appropriate for high value sites, or situations where functional turf cover is needed very quickly.

Use proper methods for sod installation.

- Specialized care for handling and establishment are required. Sod must be installed ASAP after harvest (normally within 24 hours). Prevent sod rolls or pieces from drying out and protect from overheating prior to installation.

- Sod can be installed any time soil is not frozen (for best results, soils should be warm enough for root growth: > 50º F).

- Soil on sod should be as close as possible to soil on site; this reduces potential for layering problems.

- Site preparation is virtually the same as for seeding (finished grade; lime and fertilizer according to soil test; firm, granular planting bed), with the planting bed being slightly firmer, but not compacted.

- Moisten (don’t soak) sod prior to installation.

- Lay sod by staggering the seams, perpendicular to slope. Stake or staple on slopes greater than 10%.

- Roll sod lightly to eliminate air pockets and ensure soil contact.

- Irrigate sod deeply as soon as possible after installation, enough to wet the underlying soil... this helps to promote good rooting and establishment.

- Fill in any seams that open with seed/soil/compost “divot mix”.

- With sod, post-plant fertilizer applications must be delayed until the root system is well developed and has knit strongly into the existing soil.

Pay attention to sod thickness for specialized installations.

- Sod thickness refers to the amount of soil attached to the sod and does not include shoots or thatch.

- Sod is often available in various thicknesses, typically ranging from 1/2” to 2”, and also various widths.

- Different sod thicknesses suit different applications:

Thinner sod = lower cost = lower initial stability = faster establishment

Thicker sod = higher cost = higher initial stability = slower establishment

- Thicker cut sod is most often used for specialized installations (typically sports fields where play will happen shortly after installation), and is not necessarily appropriate for lawns.

OBJECTIVE: Provide attentive post-planting care to promote turf growth and development during the establishment period.

Understand that careful attention to moisture during the establishment period is a critical aspect of any planting project.

- Adequate moisture is required not only to initiate the seed germination process, but also to sustain young seedlings before their root systems are fully developed. In the case of sod, adequate moisture is necessary for the sod to root down into the soil on the site.

- Too little water will cause seedlings or sod to dry out, which could result in delayed development or death of plants.

- Too much water can inhibit germination, rooting and shoot growth, promote disease problems ("damping-off") and may cause washing of seed and soil.

- The basic approach is to keep the planting site evenly moist but not soggy, and to gradually scale back irrigation as the turf, in particular the root system, develops and matures.

- At first, water frequently to a shallow depth. As seedlings mature, gradually taper the frequency of irrigation while increasing the duration of each irrigation event to water more deeply, eventually recharging the root zone and allowing for some soil drying between irrigation events.

Use compatible mulches when planting from seed to enhance establishment and protect the soil.

- The best mulches are weed-free, bio-degradable, and non-smothering.

- Mulches can be used during establishment to:

- Retain moisture, and help with tricky water management

- Help prevent soil erosion, especially on slopes

- Protect seed/seedlings from movement due to washing or wind (keep seed in place)

- Protect seed/seedlings from foraging animals or birds

- Buffer temperature fluctuations

- Mulch types:

Mulch types Features Loose ‘straw’ mulches

Seek out ‘clean’ straw such as oat or barley. Avoid local ‘hay’ due to high potential for undesirable weed seeds.

Straw and wood-fiber netting:

Fast, uniform coverage, but higher cost than loose straw options. Very good erosion control. Most are bio-degradable, leave-in-place systems.

PennMulch or similar products:

Made from recycled newspaper and include water-holding polymers, similar to hydroseeding mulch.

Pay particular attention to fertility during the establishment period.

- Establishing turf uses available nitrogen very quickly. Watch for slow growth, yellowing, and other signs of nutrient deficiency.

- Maintain fertility, especially N, to maintain vigorous growth and prevent deficiency.

- If establishing turf needs a fertility boost, apply up to an additional 0.5 lbs N/1000 ft2 from a mostly readily available source when establishing turf is at least 2-3 inches high. Use special care that such an application does not result in burning.

- In the case of sod projects, post-plant fertilizer applications must be delayed until the root system is well established. This process may take up to six weeks, or longer. Nutrients applied too soon will not benefit the plants and have a higher probability of loss to leaching and runoff.

Begin mowing as soon as the turf can withstand traffic.

- Mowing is a key step for turf establishment, as mowing stimulates tillering which is the primary driver of turf density.

- When dealing with new turf, the best way to time the first mowing is to use the '1/3 rule’ as a general guideline.

- Accordingly, an appropriate mowing height should be determined in advance, and the turf should be cut when it reaches a height around the 1/3 rule threshold. In other words, when seedlings reach a height about ⅓ higher than desired lawn height, and can withstand traffic, begin to mow to a height appropriate for the species and use.

- If concern exists about traffic or compaction on the site, opt for smaller lighter walk-behind equipment for the first few mowings, as opposed to larger, heavier riding equipment.

- The 1/3 rule can also be used to determine the appropriate mowing frequency as the turf matures.

Stay on top of weeds.

- When feasible, mechanically remove weed infestations from newly established lawns.

- Annual weeds will eventually mow out of new turf.

- Do not apply weed control materials until turf is well established - consult the product label for specific timing information.

- Follow label instructions of any herbicide carefully to avoid damaging young turfgrass plants. Spot treat whenever possible.

OBJECTIVE: Re-plant when turf performance deteriorates below an acceptable level and cannot be improved through normal cultural practices.

Choose a re-planting approach that fits the situation.

There are two general categories of re-planting:

- Renovation (less disruptive) – Process of replacing the turf plants on a site without making changes to the soil or grade. Does not normally include total removal of existing turf, but usually includes eradication of the existing stand with non-selective herbicides or extended covering. May include some superficial cultivation in the interest of promoting seed-to-soil contact.

- Re-construction (more disruptive) – Involves wholesale removal of existing turf on a site in conjunction with tilling or other soil cultivation, at least to the depth of the root zone, or deeper. Frequently includes addition of soil amendments, addition of topsoil, and/or changes to grade.

Choose renovation when turf has deteriorated due to stress, pest damage or unadapted grasses, but the soil and overall growing environment remain generally suitable.

- A general guideline is to renovate when 50% or more of the turf is composed of undesirable grasses or weeds.

- Renovation is a great opportunity to more closely match grass species and varieties to site conditions.

- When circumstances or budget do not permit a justifiable re-construction, a renovation approach will most often yield measurable improvement.

- Even in situations where the means and need for re-construction exist, opting for renovation first can delay major disruption and may at best have satisfactory results and at least buy some time (perhaps multiple seasons) before the larger investment of funds and energy in a wholesale re-construction project.

- Time renovation projects to coincide with an opportune time for turfgrass growth and development.

Evaluate the site prior to beginning the renovation process, and correct factors that may have contributed to turf deterioration.

- The turf may be in poor condition because of unadapted grasses, extensive thatch accumulation, excessive disease and/or insect damage, a heavy infestation of difficult-to-control weeds, or a number of other factors.

- An important step in renovation is to eliminate whatever factors caused poor quality, followed by re-planting. Renovation will only yield temporary improvement unless the original factors that led to poor quality are remedied.

Control all weeds present prior to planting.

- Most broadleaf weeds can be selectively eliminated by using commonly available herbicides. When infestations are small, spot treatments may be effective.

- Follow label directions for appropriate intervals following herbicide application before proceeding with renovation in order to allow for complete herbicide uptake and allow any chemical residues in the soil to dissipate.

- It may be advisable to permit the lawn to grow slightly higher than normal prior to weed control to allow the weeds to grow larger, thus producing more leaf area for better herbicide uptake and control.

- Small infestations of bunch type (non-spreading), weedy grasses can be removed by digging. Remove the weedy grass and soil to a depth of about 2 to 3 inches. Remove soil for a distance of about 2 to 3 inches outside of the clump to ensure the removal of all parts of the undesirable plant. Spot treatments with a non-selective herbicide that allows for seeding quickly following treatment may also be effective.

- Perennial weeds which spread via rhizomes (underground creeping stems) or stolons (above ground runners) cannot be controlled by digging, and are more effectively controlled using a non-selective herbicide.

Fertilize and lime if necessary.

- Proper soil fertility and pH are essential for successful renovation.

- Application rates of fertilizer and lime should be based on soil test results. For more information, refer to the Soil and Nutrient Management chapter of this document.

- Obtain a soil test at least 3 to 4 weeks prior to renovation, if possible.

Prepare the seedbed.

- Mow as low as possible, somewhere in the range of 1/2 inch to 3/4 inch is a good target

- If there is an appreciable accumulation of thatch (especially if more than 1/3 inch), remove it at this time using a de-thatcher, power rake or vertical mower.

- To provide a good seedbed and help ensure good seed-to-soil contact, use a de-thatcher set to penetrate the soil to a depth of about 1/4 inch. Smaller areas can be hand-raked to loosen the soil to the proper depth.

- When raking or dethatching, do not remove more than 50 percent of the dead debris because the remaining debris serves as mulch, which protects against soil erosion and seed displacement, and helps with moisture retention.

- Remove all loose debris prior to seeding.

- Power slice seeding is an additional, very effective approach that combines the cultivation and planting steps and yields superior seed-to-soil contact.

Seed the area.

- Use seed from a mix an/or blend similar to that in the existing turf unless improper turfgrass selection was the original cause of poor performance. In the latter case, match new species and varieties to the growing environment on the site, the intended use of the turf, and the management program (see the Turfgrass Selection: Species and Varieties chapter of UMass Extension’s Professional Guide for IPM in Turf for Massachusetts).

- Apply seed uniformly over the area to be renovated. To help insure uniform coverage, apply the seed in two directions at right angles to each other.

- Rake lightly following seeding (a leaf rake works well), or drag with a drag mat to work the seed into the soil to a depth of about 1/4 inch.

- Roll the area if possible to promote good seed-to-soil contact.

- If the area being renovated is on a slope, application of weed-free mulch may be necessary to prevent erosion.

Provide follow-up care for the site.

- Water lightly and frequently, two to three times per day if necessary, to keep the seed bed damp during the period of germination and establishment.

- When seedlings reach a height about ⅓ higher than desired lawn height, and can withstand traffic, begin to mow to a height appropriate for the species and use.

Consider full-scale re-construction when there are ongoing problems that go beyond just the plants present.

- Re-construction provides opportunities not typically available in a perennial turf system including ability to incorporate fertilizer and soil amendments, improve drainage, and alter the grade.

- In other instances, digging may be required to remove boulders or buried debris, or to install physical infrastructure such as irrigation system components.

- Compared with renovation, re-construction is more expensive, time-consuming, labor intensive, and functionally and aesthetically disruptive.

- Cultivation can damage soil structure, introduce the possibility of soil erosion, and stir the 'seed bank'.

- In the majority of circumstances, therefore, complete re-construction should be based on identifiable need or, from a strictly agronomic perspective, treated as a last resort.

After tillage and eradication of existing turf, the steps for re-construction are identical to the practices for new establishment outlined in the first part of this chapter.

OBJECTIVE: Use specialized establishment practices to effectively maintain turf cover and density.

Overseed regularly to maintain adequate turf cover and density.

- Overseeding is the process of introducing seed into a living, often established stand of turf, in order to make repairs or to maintain adequate turf density.

- Overseeding is a key practice on heavily-trafficked areas and sports fields.

- When overseeding is performed to gradually introduce different grass species or cultivars and alter the stand composition over time, it may also be referred to as interseeding.

Use effective overseeding methods.

- Like renovation, overseeding requires superficial cultivation to promote seed-to-soil contact.

- Common approaches include broadcast seeding following disruptive practices such as aeration, dethatching, or topdressing.

- Power slice seeding is a very effective, efficient, and minimally disruptive overseeding method.

Take turfgrass selection into account when overseeding.

- Because of competition with existing, living turf, faster-establishing turfgrass species such as perennial ryegrass are best-suited for overseeding.

- Slow-establishing grasses, particularly bluegrasses, are more challenging to overseed successfully.

- For better results with slower grasses, suppress existing turf with moderately close mowing prior to overseeding. This can also be accomlplished with plant growth regulators in more sophisticated programs.

- Continue mowing regularly; base mowing frequency and height of cut on mature grasses present.

Repair thin or bare patches regularly, on an as needed basis.

- Loosen soil if necessary or aerate with core aeration or vigorous raking. ‘Garden Weasel’ type cultivators are an excellent tool for small patches.

- Apply seed.

- Topdress with fine finished compost or mulch.

- Irrigate in the same manner as for new seedings.

Pre-germinate seed for very quick repairs.

- Place seed into a cloth sack.

- Submerge sack into a bucket or barrel of water and soak for at least 12 hours. Sufficient time may vary depending on grass species selection.

- Aerate by lifting the bag out of the water and placing it back several times every few hours, or bubble air into the water.

- Spread seed out to dry it sufficiently for application in a drop or rotary spreader or a slice seeder, and/or combine with a "carrier" such as compost or other topdressing material.

6. Irrigation and Water Management

OBJECTIVE: Reduce water use for turf management to the lowest possible level, to conserve and protect our most precious natural resource.

Implement water conservation strategies on the basis of both responsibility, and cost savings.

- The demand for potable water (drinking water) for agricultural, residential, and industrial use is expected to increase in the future while our supply of water will remain essentially unchanged.

- When rainfall is insufficient and water resources become limited, supplemental irrigation required to sustain plantings such as lawn and landscape turf is often the first to be placed on water use restrictions. Be sure to comply with local and state water use regulations and restrictions.

- Increased costs accompany tightening water availability; minimizing water use can enable greater budgetary efficiency.

Understand that replacement of turf areas with tree and shrub plantings won't necessarily conserve water.

- The use of trees, shrubs and other ornamental plantings in the landscape in lieu of turf does not necessarily suggest low water use or minimal maintenance.

- In studies that are available, which compare water use or evapotranspiration (ET), trees and shrubs have been regularly found to be higher water users than turfgrass.

Example: on average, research has demonstrated that one mature oak tree can have water requirements equivalent to 1800 ft2 of turf. This in large part is due to the greater leaf canopy surface area that is exposed to atmospheric (evaporative) demand.

- Adjacent trees and shrubs in the landscape commonly benefit from irrigation that may be applied to turf areas.

Be familiar with the concept of evapotranspiration (ET).

- Evapotranspiration is the sum total of water lost to the atmosphere due to evaporation from the soil surface plus transpirational water loss associated with leaf surfaces.

- In high density turf where 95% of the soil surface may be shaded by leafy vegetation, the major contributor to ET is transpiration.

- ET increases with increasing solar radiation, high temperatures, wind, and decreasing relative humidity.

Select turfgrass species and cultivars with demonstrated water use efficiency when possible and appropriate.

- Many modern turfgrass varieties have been developed to provide acceptable function and quality with reduced water input.

- By selecting turfgrass species (and cultivars) that have scientifically documented low water requirements or superior drought resistance, the turfgrass practitioner can delay or postpone drought stress injury and associated decline in turfgrass quality and function during extended periods of little or no water.

- Turfgrass species and cultivars with low leaf area (slow growth rates, narrow leaf width), high leaf and shoot densities, and horizontal leaf orientation use less water. Kentucky bluegrass varieties can vary by as much as 30% in their ET rate due to these plant (morphological) factors.

- Note that low water use does not necessarily equate to superior drought resistance because rooting depth is also an important drought resistance component.

OBJECTIVE: Carry out management practices with responsible water use as a priority.

Minimize supplemental irrigation to the lowest level required for the desired degree of turf performance.

- Irrigation should be applied at the onset of mild drought stress to recharge the root zone, unless dormancy is allowable on the site.

- Incorporate hand watering into the management program when appropriate.

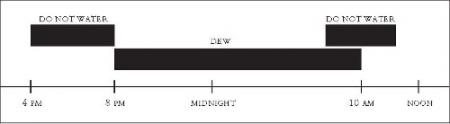

- Irrigation should be timed in order to minimize duration of leaf wetness so as to reduce the incidence of diseases.

- Test water for irrigation suitability. Water department or board of health test results can often be accessed for this information.

- Maintain and adjust irrigation systems according to weather conditions.

- Supply adequate water for establishment, renovation, repairs, and overseeding.

Follow the ‘⅓ Rule’ when scheduling mowing events.

- Regular and frequent mowing helps to minimize water loss through reduced leaf area and turfgrass ET.

Maintain sharp mower blades.

- Dull mower blade injury can increase water use by delaying the healing of open wounds following mowing events. These wounds also promote disease infection.

Raise the height of cut (HOC) as summer progresses.

- Higher mowing heights promote deeper rooting and therefore access to greater amounts of soil water. This is especially true in spring when 60% of the total annual root mass is produced.

- Keep in mind that higher HOC can increase leaf area and hence ET losses during hot and dry conditions. Irrigated turf may be able to withstand lower HOC in summer than non-irrigated turf.

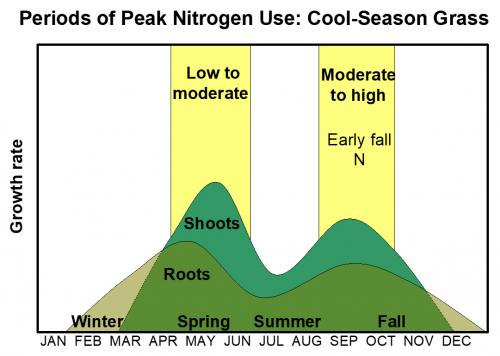

Apply fertilizer nitrogen at minimal levels timed to specific needs of turfgrass.

- Nitrogen (N) promotes leaf area (and ET) and reduces rooting depth, thus increasing the need to irrigate.

- For maximum water conservation, nitrogen, especially water soluble N, must be kept to the lowest possible level needed to sustain turf performance.

Apply potassium in balance with nitrogen.

- Potassium (K) is a nutrient that is important to turf during stress periods.

- Soil testing is needed to identify K deficiencies.

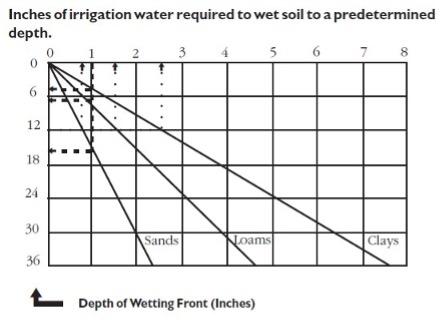

- If soil K levels are adequate based on a soil test, then K should be applied at levels that are approximately 25% to 50% of the total annual N.